Author: Anika Bajpai

Mentor: Emma Sarro, PH.D

Archies Higher Secondary School

Abstract

Dementia is an increasingly common syndrome and while pharmacotherapy is available, its potential benefit is limited, especially in non-cognitive, emotional outcomes. Non-pharmacotherapy such as music therapy is thought to be associated with improved outcomes. There is strong evidence that engaging with music and art related activities can improve our health and well-being. Music-based interventions, approaches and practices, such as group music-making which includes singing or playing musical instruments, listening to music and music therapy, have all been shown to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety.

The goal of this descriptive overview is to provide a broad overview of this field by bringing together research examples from various practises and research disciplines. Selected evidence is examined, and presented to show how music-based interventions, approaches, and practises can reduce labour anxiety and pain, improve language function, orientation, and memory scores, and support brain structures associated with reward and pleasure experiences.

The examined research includes single studies and reviews that use both qualitative and quantitative methods. Overall, we highlight how music and other potential behavioral therapies, employed in a variety of ways, may support mental health with the aim of stimulating more interest and research in this area.

Keywords: music therapy, dementia, systematic review, behavioural therapies, art therapy in dementia etc.

Introduction:

Alzheimer’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that severely impairs memory and thinking skills and, ultimately, the ability to perform simple tasks. For most people diagnosed with the disease – especially the form known as a type of “late arrival”, symptoms begin to appear in the age group of 60-64 years.

[Wikipedia contributors. (2021, September 1). Addiction-related structural neuroplasticity. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14:53, October 22, 2021]

Some of the symptoms found in other forms of AD early onset AD, are memory loss, vision loss, experiencing personality and mood changes. In reference to the major symptoms, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia among older adults. Detailed neuropsychological testing can reveal mild cognitive difficulties up to eight years before a person fulfills the clinical criteria for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. People who have this form tend to have more of the specific brain alterations that are linked with Alzheimer’s. Furthermore, a form of muscle twitching and spasm, called myoclonus, is also more common in early onset Alzeihmer’s. The early-onset form also appears to be linked with a defect in a specific part of a person’s DNA: chromosome 14.[https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/alz.12068]

While the exact causes of Alzheimer’s disease aren’t fully understood, scientists believe that for most people, Alzeihmer’s disease is caused by a combination of genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors that affect the brain over time. Moreover, there are a number of measurable changes in the brain that can be associated with the disease. At a basic level, for most neurodegenerative diseases, brain proteins fail to function normally, disrupting the work of neurons to control our normal activity and through a series of toxic events, neurons are damaged, lose connections to each other and eventually die. This particular disease is named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer who noticed changes in a woman’s brain tissue after she died of an unusual mental illness in 1906.

Memory loss, language difficulties, and erratic behaviour were among her symptoms. He examined her brain after she died and discovered many abnormal clumps (now known as amyloid plaques) and tangled bundles of fibres (now called neurofibrillary, or tau, tangles). These plaques and tangles in the brain are still considered to be some of Alzheimer’s disease’s hallmark symptoms. The loss of connections between nerve cells (neurons) in the brain is another feature.

As neurons die, additional parts of the brain are affected. By the final stages of Alzheimer’s, damage is widespread, and brain tissue has shrunk significantly.[https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-alzheimers-disease]

Currently several prescription drugs are approved and used by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to help manage symptoms in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Most medicines work best for people in the early or middle stages of Alzheimer’s. However, it is important to understand that as of now, none of the medications available at this time have been shown to be Alzheimer’s. The following describes several of these medications. Aricept is the only treatment approved by the FDA for all stages of Alzheimer’s disease: mild, moderate, and severe. Razadyne is also for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s. Exelon is for people who have mild to moderate Alzheimer’s. Mematine treats moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. It works by changing the amount of a brain chemical called glutamate, which plays a role in learning and memory. Brain cells in people with Alzheimer’s disease give off too much glutamate. Namenda keeps the levels of that chemical in check by blocking the receptors. It may improve how well the brain works and how well some people can do everyday tasks. The drug may work even better when you take it with Aricept, Exelon, or Razadyne. Namenda’s side effects include tiredness, dizziness, confusion, constipation, and headache.

[https://www.webmd.com/alzheimers/news/20141229/combo-pill-alzheimers-disease]

Namzaric contains a combination of donepezil( also called Aricept) and memantine( also called Namenda) . Donepezil improves the function of nerve cells in the brain. It works by preventing the breakdown of a chemical called acetylcholine. People with dementia usually have lower levels of this chemical, which is important for the processes of memory, thinking, and reasoning. Memantine reduces the actions of chemicals in the brain that may contribute to the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. It’s best for people with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s who already take the two drugs separately.

Because of its debilitating Alzheimer’s disease, many antiretroviral drugs also offer many unwanted side effects because of their harsh nature. Interestingly and also important in this review, cognitive interventions have found a lot of attention to many psychiatric disorders. This could include the use of computer-based training programs, which have shown superior performance in delayed memory development, recognition, clock drawing, digital forwarding and back-to-back testing. These programs, however, can cost and expose learning barriers for adults who may opt for traditional pencil and paper methods.

On the other hand, in recent years, music and art interventions have grown in popularity as a non-pharmacological and alternative treatment for people with AD for a number of reasons. In addition to medications and cognitive-based therapies, music therapy offers cheap interventions that reduce the stress and side effects associated with other therapies. Music therapy has been studied in the psychological community and has been found to be effective in reducing behavioral symptoms and positively affecting emotional and mental well-being.

In this review, we will take a closer look at existing literature on music and artistic interventions that include people with dementia and Alzheimer’s. First we will summarize whether behavioral methods (such as art and music) are more effective compared to the pharmaceutical methods used and second, we will examine whether they have a significant impact on understanding and behavior if patients are actively involved or just watching / listening. We think that behavioral therapies, such as music therapy, will be useful or complementary to the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease because it has no side effects and is not addictive.

Methods

For this review, a literature research was carried out using primarily the following databases: NCBI, PubMed, ScienceDirect , Google Scholar search engine to collect all of the literature cited. In our search, the parameters included studies published in the last 10 years, and available in English. Keywords used to search included: music therapy, art therapy, dementia, behavioural therapy, non pharmacological intervention. The studies gathered in our review included only patients with AD dementia. The patients were in the age bracket of above 60 years of age.

We relied on the above-mentioned search engines for assistance and data. We wanted to include review papers with experimental evidence of the impact of behavioural therapies on the cognitive abilities of Alzeihmer’s patients’ brains. In the end we included a total of roughly 30 articles.

The purpose of this narrative review is to investigate the effectiveness of behavioral therapy intervention strategies (pharmaceutical therapy vs. behavioral therapy), so many articles contained these interventions for our data collection. A literature research was carried out using the following databases: NCBI, PubMed, ScienceDirect , Google Scholar

All clinical trials were used to create a more comprehensive review. These included interventional trials randomized controlled trials, observational trials, case-control studies, systematic reviews etc

Furthermore, this study focused majorly on the music and art therapies: thus, the type used in the intervention (individualized vs. non-individualized music) on cognitive and behavioral outcomes for persons with AD was another important factor when choosing articles

Results

Music therapy has strong neuroscientific and psychological foundations. Individuals’ psychological and physiological health can be improved through music therapy. In this study, we discovered that music has a significant effect on our brain, particularly in the nucleus accumbens, amygdala, and cerebellum, which are responsible for emotional responses.

Non-pharmacotherapy, such as music and art therapy, has been linked to better outcomes. We evaluated and demonstrated the effects of music therapy on dementia patients in order to determine its potential benefits.

Positive

In a systematic review of 5 randomized controlled trials, Vink et al. (2004) investigated the effects of music intervention on the treatment of behavioral, emotional, cognitive, and social problems in older adults with dementia. He concluded that music interventions are more likely to have positive effects on cognitive skills, quality of life, and complexity (as shown in Figure 1), but acknowledged that methodological errors and inconsistencies in published work in 2004 reduce the strength and comparability of reported findings, reducing any conclusions that can be drawn.

Another positive effect of music therapy is shown by Koike et al. (2018), presenting neural in vitro cells in the range of sound waves from 10 to 200 Hz for 30 minutes while using the sensory growth factor. You have found that between 150 and 200 Hz sounds have little effect on neurite output, but that sound between 10 and 100 Hz has caused a significant increase in neurite growth. The frequency of 40 Hz was very active, producing three times the rate of growth as NGF alone. The sound using p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), which has a major impact on neurite growth, has been shown to be a mechanism here.

[Wikipedia contributors. (2021, August 16). Disease management (health). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14:04, October 22, 2021]

Another study which supports the fact that the patients only show improvements to specific music types was performed by Hans Ragneskog RNT et al. (2018) The influence of dinner music on food intake and symptoms common in dementia such as depressed mood, irritability and restlessness was studied. The study was carried out in a nursing-home ward in Sweden. Soothing music was played as dinner music for two weeks, Swedish tunes from the 1920s and 1930s for two weeks and pop music for two weeks. Prior to these periods, there was one week without music, and at the end of the intervention there was a two-week control period. The effects of the intervention were assessed by psychological ratings and by weighing the food helpings. It was found that during all three music periods the patients ate more in total. The difference was particularly significant for the dessert. The staff were thought to be influenced by the music, as they served the patients more food, both main course and dessert, whenever music was played. The patients were less irritable, anxious and depressed during the music periods. The results of the study suggest that dinner music, particularly soothing music, can reduce irritability, fear-panic and depressed mood and can stimulate demented patients in a nursing-home ward into eating more.[Ragneskog, H., Bråne, G., Karlsson, I., & Kihlgren, M. (1996). Influence of dinner music on food intake and symptoms common in dementia. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences, 10(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.1996.tb00304.x]

Hei long lam et al. (2018) conducted a study to show the effects of singing on memory, which examines the idea of active involvement (as shown in Figure 2)

Results for the effect of music therapy on the memory of patients living with dementia were mixed, with 4 out of 5 studies reporting significant improvements. (see table 1 ) Two RCTs assessed the effects of singing on memory; one study reported significant improvements in memory, as measured by a comprehensive battery of neuropsychological tests. It is worth noting that significant improvements in memory occurred in the two studies that used a combined music therapy modality.

Similarly, another study by Roger Y Wong et al. explored the effects of music listening, and reported that apathy was significantly reduced in which active music therapy was implemented (using musical instruments and combined music therapy respectively) in 137 patients. There were improvements in apathy levels in the intervention group in which live music was played, but no significant effect was observed for the group in which pre-recorded music was played. This suggests that patient participation might be a factor affecting apathy.

Art Therapy

Interestingly, we found that some have approached alternative therapy by way of art. Kinney et al (2018) used an intervention to encourage patients with mild and moderate dementia to express themselves through artistic activities while also providing sensory stimulation; the patients experienced the joy of creation and gained satisfaction and a sense of self-worth through the challenging creative process, thereby improving their well-being and quality of life. They were happy at the end of the procedure and exuded self esteem and confidence (as shown in Figure 3)

Similarly, Shinichiro et al (2014) discovered that after participating in art colouring activities for 12 weeks, five dementia patients had lower scores on wandering, excretion, and calling for no reason, as well as an increase in daily average sleep time from 4.5 to 7.9 hours, easing caregivers’ burden.

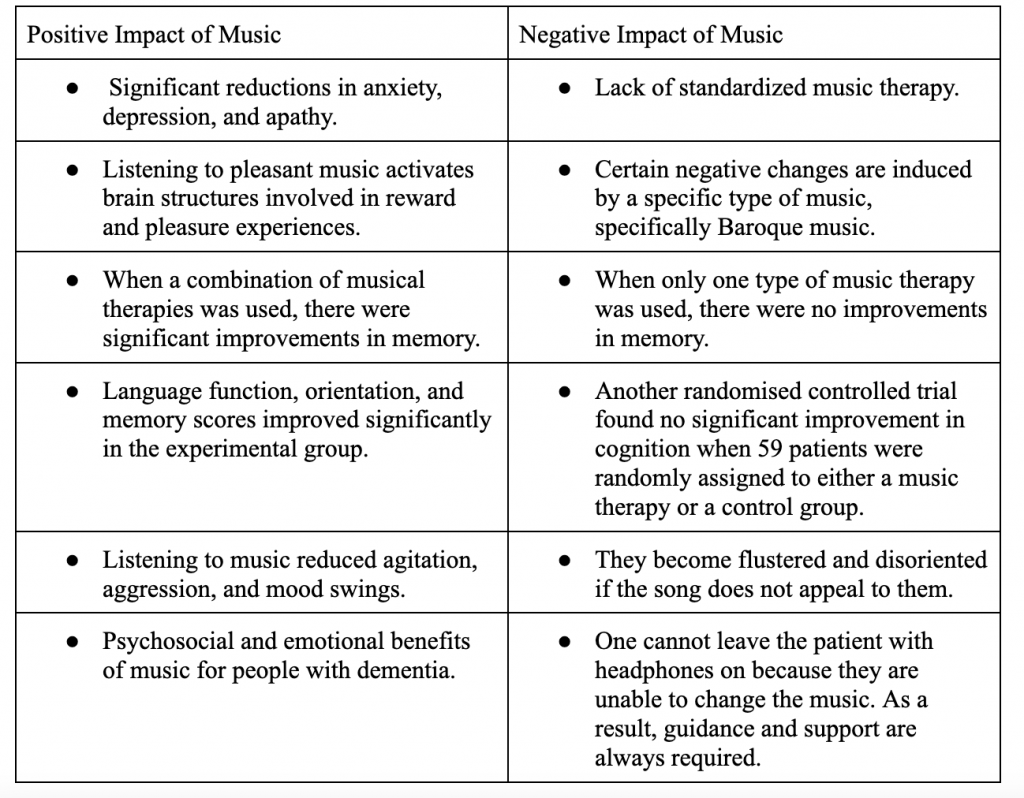

Negative

However there are some studies that do not support the benefits of music intervention. Table 1 below provides the positive as well as the negative impacts of musical therapy.

Shiltz, DL, et al. conducted research to investigate the effects of combining music therapy with other therapies. While six of the eight studies found that listening to music reduced agitation, mixed results were obtained in studies looking at the effects of integrated music therapy, which often included listening to music. It is noteworthy that when Baroque music was played in 75 patients in a crossover trial, there was a significant increase in the number of episodes of outrageous behavior while playing music. So while many forms of music can help reduce stress and mood swings, there may be subtle conflicts with other forms of music, such as Baroque music, which may be more musical and complex, and may increase the agt levels of patients’ anonymity, thus creating a negative effect. The short-term benefits of music therapy in reducing the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and quality of life, may be due to reduced emotional comfort and safety, which may not last long, and therefore, may not improve the quality of life for patients living with dementia.

Animal studies for evidence

It is important to note that, in addition to human studies, there are several geological studies of various species that strongly support the impact of a rich neurological environment on memory (as shown in Figure 4)

Amy Shephard et al. taking into account the time difference and duration of EE intervention in the APP / PS1 mouse model in this review. A novel object recognition task with Barnes Maze was used to test the understanding of animals kept in EE conditions for between 3 and 6 months. They found that both of these interventions improved performance in the novel object recognition function, regardless of when they were used or how long they were acquired in it, but it was a version of the work that tested temporary memory.

Discussion

Our systematic review illustrates that behavioral therapy is an important, perhaps even indispensable, tool to gain such knowledge. Future work with music and art can contribute to the investigation of the neural connections underlying different emotions, with the particular advantage that music and art can be used to study a range of positive as well as negative emotions.

Music has a high likelihood of improving cognitive abilities, quality of life, and agitation. One of the key findings of this study was that patients only responded to a specific type of music. It covered everything from the frequency of music to the genre of music and how the music was connected to the patients’ lives. This suggests that lyrics in music therapy pieces may play an important role in memory formation activation and, as a result, improve verbal fluency in dementia patients.

Also, as we saw in the review, music therapy only has short-term benefits and does not completely cure dementia; we can use pharmacotherapy, such as cholinesterase inhibitors, which have been linked to improvements in cognitive function and daily activities, whereas music therapy has been linked to improvements in verbal fluency as well as reductions in anxiety, depression, and apathy.

In addition, Art therapy induces significant positive changes in the brain that stimulates the temporal lobe, which affects object recognition and accurate expression using language, and the parietal lobe, which perceives the spatial position of objects and controls fine motor functions of the hand.

Additionally, art therapy provides an effective way to train patients in the capacities of language and fine motor movement of the hand, in which the hand-brain interaction helps maintain and develop motor skills and coordination and improves the perception by the brain of color, shape, space, proportion, etc. Interestingly, there are also a few studies that report a benefit of doll therapy. For people who are withdrawn, restless, distressed, or anxious, holding or simply being with a doll or soft toy animal, such as a cat or dog, can improve their wellbeing and ability to communicate.

It may bring back memories of when they had small children or a pet of their own.

Caring for a doll or soft toy can give dementia sufferers a renewed sense of purpose and allow them to reconnect with the outside world. [Catarina, M. C. (2014). A review on auditory space adaptations to altered head-related cues.]

Interestingly, our review shows that there are certain negative impacts of music on general cognition and related aspects such as memory, orientation, and registration. While most forms of music might be helpful in relieving behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, there might be subtle differences with some types of music, specifically Baroque music, which might be more musically activating and complex, and which could unknowingly increase the agitation levels in patients. To counteract this problem one can probably contact the families of the patients and ask for a list of their favorite songs as it could play an important role in memory formation activation, and hence improve verbal fluency in patients living with dementia.

Further, even if one considered art therapy as playing a certain role in monitoring the disease, detecting changes in a patient’s condition and prognosis, there was a lack of universality, making it difficult for average family caregivers to comprehend the use of art therapy in dementia assessment without systematic education and training. Art therapy requires that patients have hand function and the ability to complete simple tasks; although this approach has been recognized to reduce the behavioral and psychological symptoms of patients, art therapy has had mixed outcomes in improving the patients’ cognitive abilities. Therefore due to the limited number of related studies, there are variations regarding the duration, frequency and measuring tools of the intervention, which must be improved in future investigations.

While we didn’t find a clear measurable improvement in memory, the animal studies suggest something clear in how enrichment changes the brain and behavior, so there might be a real benefit to music with pharmaceutical treatment. Therefore, although several questions remain, better insight into the neural basis of emotions evoked by music and art will lead to a better understanding of how to employ music and art in the therapy of affective disorders.

Conclusion:

Although there does not appear to be any proven benefits on memory quantification, music therapy may improve verbal fluency and reduce anxiety, depression, and apathy in some dementia patients. More clinical trials are needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn about the therapeutic value of music therapy for dementia patients.

References:

- Davis, W.B.; Gfeller, K.E.; Thaut, M. An Introduction to Music Therapy: Theory and Practice; American Music Therapy Association: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2008.

- Li, C.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.; Chou, M.; Chen, C.; Lai, C. Adjunct effect of music therapy on cognition in Alzheimer’s disease in Taiwan: A pilot study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2015, 11, 291.

- Särkämö, T.; Tervaniemi, M.; Laitinen, S.; Numminen, A.; Kurki, M.; Johnson, J.K.; Rantanen, P. Cognitive, Emotional, and Social Benefits of Regular Musical Activities in Early Dementia: Randomized Controlled Study. Gerontologist 2013, 54, 634–650

- Holmes, C.; Knights, A.; Dean, C.; Hodkinson, S.; Hopkins, V. Keep music live: Music and the alleviation of apathy in dementia subjects. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2006, 18, 623–630.

- Peretz, I.; Gagnon, L.; Hébert, S.; Macoir, J. Singing in the Brain: Insights from Cognitive Neuropsychology. Music Percept. 2004, 21, 373–390.

- Lam HL, Li WTV, Laher I, Wong RY. Effects of Music Therapy on Patients with Dementia—A Systematic Review. Geriatrics. 2020; 5(4):62.

- Ale Bahar – Fuchs , Anthony Martyr, Anita My Goh, Julieta Sabates, Linda Clare.Cognitive training for people with mild to moderate dementia. 2019; 3(3)

- Richards AG, Tietyen AC, Jicha GA, et al. Visual Arts Education improves self-esteem for persons with dementia and reduces caregiver burden: A randomized controlled trial. Dementia. 2019;18(7-8)

- Shepherd A, Zhang TD, Zeleznikow-Johnston AM, Hannan AJ, Burrows EL. Transgenic Mouse Models as Tools for Understanding How Increased Cognitive and Physical Stimulation Can Improve Cognition in Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Plast. 2018 Dec 12;4(1)

- Cooke ML, Moyle W, Shum DH, Harrison SD, Murfield JE. A randomized controlled trial exploring the effect of music on agitated behaviours and anxiety in older people with dementia. Aging Ment Health (2010) 14:905–16.

- Raglio A, Filippi S, Bellandi D, Stramba-Badiale M. Global music approach to persons with dementia: evidence and practice. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1669-1676.

- Clements-Cortes A and Bartel L. Are We Doing More Than We Know? Possible Mechanisms of Response to Music Therapy. 2018; Front. Med. 5:255.

- Ragneskog, H., Bråne, G., Karlsson, I., & Kihlgren, M. (1996). Influence of dinner music on food intake and symptoms common in dementia. Scandinavian journal of caring sciences, 10(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.1996.tb00304.x

- Wikipedia contributors. (2021, August 16). Disease management (health). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14:31, October 22, 2021, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Disease_management_(health)&oldid=1039008299

- Stefan, S. S. (2017). Effects of Music on Agitation in Dementia: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00742/full

- Wikipedia contributors. (2021, October 22). Dementia. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14:42, October 22, 2021

About the author

Anika Bajpai