Author: Porter McAndrews

Mentor: Dr. Nikolas Webster

St. Ignatius College Preparatory

Abstract

This research paper explores three major developments impacting college football and the greater sphere of collegiate athletics: athletic conference realignment, the current state of the transfer portal, and Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL). It reviews the history and business economics of college athletics and how incentive structures have evolved over time leading to some unintended consequences that are threatening college football’s two greatest assets, tradition and fan loyalty. It examines how various laws and National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) rules have been instituted, changing the landscape of the sport for universities and student-athletes. The paper concludes with some recommendations on actions that college football’s various stakeholders can take to meet the current challenges and support the sport’s economic health going forward.

1. Introduction

The first collegiate American football game occurred on November 6, 1869, in Brunswick, New Jersey, when Rutgers defeated the College of New Jersey (later renamed Princeton University) 6-4 in front of about 100 spectators (Richmond, 2023). From that first game, football took off rather quickly, first in the Northeast, and then spreading across the country. Within a couple of decades, colleges in every region of the United States were forming teams and playing games against each other (Bigalke, 2018).

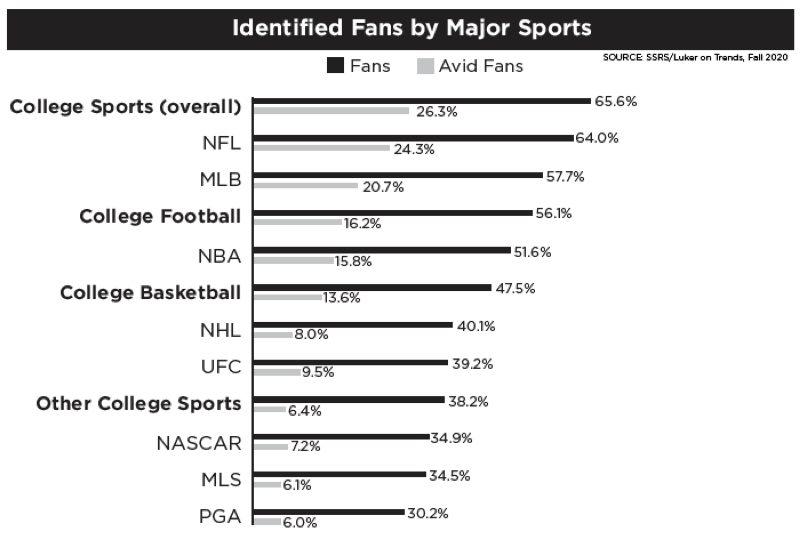

One hundred and fifty-five years after that first intercollegiate competition, college football has developed considerable fan interest. With 155 million adult and teenage fans, 45 million of whom consider themselves “avid fans,” it trails only the National Football League (NFL) and Major League Baseball (MLB) among major sports in the United States. College athletics overall have more fans—182 million— than any professional league in America. And college sports fans are 1.6 times more likely to have incomes over $100,000 compared to the overall US population (Learfield, 2021). That college football has almost as many fans as the NFL is notable given only the very best 1.6% of players move on from college to play professionally (Cesconetto, 2025). All these statistics are indicative of the appeal of college sports that transcends putting the best athletes on the field.

Figure 1. Identified fans as a percentage of the US population over the age of 12 by sports league (Learfield, 2021).

With its fan growth, college sports, primarily football and men’s basketball, has become one of the largest entertainment draws in the United States, and consequently, its management is now primarily based on what generates the most revenue. In 2022, college athletics earned approximately $13.6 billion in total revenue, with $4.2 billion (31.1%) coming from television rights (Morones & Heidt, 2023). In 2020-2021, over 538 million households (unduplicated) viewed college football and basketball on television along with 69 million fans who attended games in person. Fans spend over $3.5 billion on collegiate licensed merchandise annually (Learfield, 2021).

However, making money was not the original intended purpose of college athletics. The initial purpose was “to promote school spirit and unity, which allows students to take pride in and feel connected to the highest educational endeavor” (Padilla, 2019). An article from the Times West Virginian contends that the original intent was “as a means to have fun outside of rigorous classes” (Rhodes, 2024). Holding collegiate sports competitions for monetary reasons was not a motivation that early administrators even contemplated. But college sports have slowly shifted away from the old values of the game, such as amateurism, to focus on maximizing financial gain for the institutions involved. There are many factors driving this change, but universities, big media corporations, and college sports’ primary governing body, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), have been major contributors to the change.

A major turning point for this shift was in 1939 when college football was first broadcasted on television (Koppett, 1999). With games being available to more fans, the popularity and viewership of football grew, which in turn created increasing broadcast advertising revenue opportunities. The first televised football game in 1939 had an estimated 500-5,000 viewers (NCAA, 2025). The 2006 Rose Bowl between the University of Southern California (USC) and the University of Texas would have a record-shattering 35.6 million viewers, a four or five order-of-magnitude increase in the intervening 67 years (Reeves, 2024).

As college football, along with college basketball, have become growing sources of revenue for universities, usually subsidizing not just all other athletic programs, but the colleges’ general funds, several issues have inevitably emerged. Colleges are now increasingly switching athletic conferences in search of greater revenue opportunities. The resulting conference realignment has torn apart many historic leagues that fans have grown up with and has erased the geographical logic of many of those affiliations. This is seen most dramatically with the Big Ten Conference where universities on the West Coast (USC, the University of California-Los Angeles, the University of Oregon, and the University of Washington) now compete in the same conference with colleges on the East Coast (the University of Maryland and Rutgers University).

Even as college football has generated significant revenue for the universities, until recently, the focus of most college football players had largely stayed the same: pursuing a degree while getting an opportunity to play the sport they loved. This is because outside of receiving a scholarship and room and board, the students were forbidden from legally being compensated for playing. But as the magnitude of the money pouring into major college football kept increasing, student-athletes, their families, and many fans and pundits started demanding that the players be allowed a share of the great wealth being created by their performances. Additionally, some coaches and boosters realized that by paying athletes “under the table,” they could entice them to their schools and increase their chances of winning. Because a college coach’s value to a university is primarily measured in terms of their win-loss record, the incentives to break the law and NCAA rules to attract the best talent were irresistible to some.

Initially, illegal payments by coaches or boosters were primarily made to convince high school recruits to go to their school. Once committed to a university, it was difficult to for a player to transfer to another college, and usually required the athlete to “sit out” a season and lose a year of eligibility.

But just as there was growing public debate over whether student-athletes should be compensated for playing their sports, there was also public debate as to whether it should be easier for the athletes to transfer to other colleges. Originally the discussion focused on the idea of making it easier for young adults to correct a decision that they made as a teenager. Examples were cited of players who were homesick and wished to move a school closer to their families or of players who committed to play for a particular coach who had just departed to pursue his own career somewhere else.

So, in 2018, the NCAA created a process called the transfer portal to allow student-athletes a streamlined, transparent, and equitable means of changing schools. They also modified their rule regarding requiring an athlete to wait a year before competing and lose a year of eligibility after the first transfer (Johnson, 2019).

To address the issue of player compensation, in 2021 the NCAA adopted a policy allowing athletes to be paid legally in exchange for the use of their “Name, Image, and Likeness” (NCSA, 2024). The NCAA approved this policy, also known by its acronym, “NIL,” because of the pressure they faced from state legislatures. With the NIL policy in place, those lawmakers proceeded to pass legislation regulating NIL, though unfortunately the regulations often differed slightly in each state. Despite its flaws, this new opportunity for athletes to be compensated for their role in college sports officially marked the end to the foundational value of amateurism in the sport.

The transfer portal has been a helpful tool for athletes who were not a good fit or could not achieve their goals at their old school. But with the adoption of NIL, student-athletes have an additional incentive to change schools, namely, to shop around for the most lucrative NIL deal that they can find. So in recent years, an increasing number of athletes have not just transferred, but transferred multiple times during their college career, while others have entered the transfer portal, losing their roster spot with their current team only not to be recruited by a new school. Overall, many athletes are underestimating the risks associated with the transfer portal and not obtaining the hoped-for benefits.

College football (and basketball) appear to be at cross-roads as the economics underpinning collegiate sports has changed radically. These changes are threatening the traditions and fan loyalty that have always been a competitive differentiator for college sports when compared to professional sports. Beyond driving higher television ratings that encourage networks to invest heavily in broadcasting rights, fan loyalty translates to ticket sales, branded merchandise sales, sponsorships, alumni contributions, and ancillary game day sales for the universities (e.g. concessions, parking, etc.) and local businesses. Games between traditional rivals generate particularly high economic activity.

This paper will now take a deeper look at each of these changes and provide some recommendations on actions that college football’s various stakeholders can take to meet the current challenges and support the sport’s health going forward.

2. Collegiate Athletic Conference Realignment

2.1. The Birth of Athletic Conferences

Most of the early football games in the 1870s, ‘80s, and ‘90s were played against local competition. That led to teams forming affiliations to establish common rules and organize game schedules. In 1895, five universities in the Southeast—Alabama, Auburn, Georgia, Sewanee, and Vanderbilt—formed what would be the first collegiate athletic conference, the Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association (SIAA) (SEC Sports, 2023). The following year, eleven other colleges joined the SIAA.

Other athletic conferences were quickly formed around the nation. Of the major Division I Football Bowl Series (FBS) conferences still in existence today, the Big Ten was formed a year after the SIAA in 1896, the Big 8 (which would later rename itself the Big 12 to reflect its growing membership) was established in 1907, the Southeastern Conference (SEC) which would take in many of the SIAA’s founding members was created in 1932, and the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) was founded in 1953 (Sports Reference, n.d.).

2.2. Earliest Conference Membership Movement

Throughout the history of intercollegiate athletic conferences, universities would occasionally change their affiliations (Henry, 2023). Usually, these moves were made by individual universities for program-specific reasons. For example, Georgia Tech left the SEC in 1964, where it had been a member for thirty-two years. Georgia Tech’s decision to leave was a response to league members voting against its proposal to prohibit certain recruiting practices, such as the over-signing of players, that football head coach Bobby Dodd thought put the Yellow Jackets at a competitive disadvantage. In 1979, after fifteen years as an independent, Georgia Tech would join the ACC (Perrin & Solomon, 2008).

However occasionally an athletic conference would experience a mass exodus of teams resulting in its total collapse. That first happened to the SIAA when in 1921 and 1922, fourteen of its members left to form the Southern Conference, many in protest over the SIAA’s rejection of proposed rule changes regarding freshman eligibility and pay for baseball players (New York Times, 1920). By 1942, the SIAA folded after not being able to survive as a minor conference (Spearman, 2016).

In 1932, thirteen of the original SIAA schools would leave the Southern Conference to form the SEC. Twenty-one years later in 1953, seven additional schools would depart the Southern Conference to create the ACC (SoCon, 2024).

2.3. Collapse of the Southwest Conference

The world of college football was shaken when the Southwest Conference (SWC) collapsed in 1996. For most of its 82-year history, the SWC was one of the preeminent football leagues with Texas-based powerhouses like the University of Texas, Texas A&M, Texas Tech, and the University of Houston. However, in the late 1980’s, the conference was marred with a string of scandals, the biggest of which resulted in the NCAA giving SMU the “death penalty” as punishment for its boosters paying recruits to play for the university. The University of Arkansas, always a bit of an outcast as the only school in the league not from Texas, was the first to leave the conference for the SEC in 1992 as the SWC was losing appeal and in turn losing television viewers and ad revenue (Fertak, 2013). Then in 1996, Baylor, Texas, Texas A&M, and Texas Tech all left the SWC to join the Big 8 and form a renamed conference, the Big 12. This was the first time several schools all left one conference for another as a group in search of improved revenue opportunities resulting in their former conference collapsing (Dufresne, 1996).

2.4. Maryland and Rutgers Leave the ACC for the Big Ten

The next considerable disruption to the nation’s major athletic conferences was in 2014 when Rutgers University and the University of Maryland were lured away from the ACC to join the Big Ten. Rutgers and Maryland were enticed by the greater revenue opportunities offered by the Big Ten. The Big Ten wanted members from the lucrative New York and Washington, DC/Baltimore television markets to expand its marketing appeal and revenue (Mandel, 2014).

2.5. Texas and Oklahoma Pay the Big 12 to Jump to the SEC

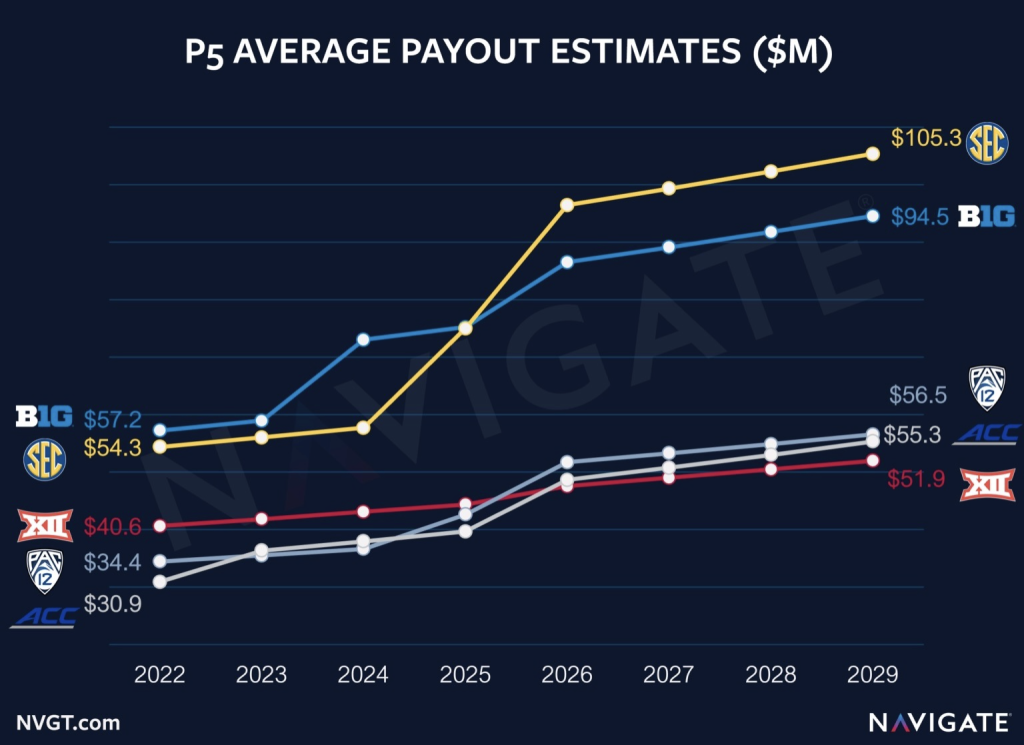

In July of 2021, the University of Texas and the University of Oklahoma announced that they would be leaving the Big 12 Conference and joining the SEC heading into the 2025-2026 season. The reason for this move was the opportunity to make more media revenue as part of the SEC (Young, 2021). Over the previous sixteen years, the SEC had completely dominated the college football rankings with eleven of the national champions coming from their conference (and two more the next two years). The Big 12’s lone champion in this timeframe was Texas, exactly sixteen years ago (NCAA, 2024). Because of this domination, the disparity in media rights deals between the leagues had grown significantly so that by 2022, each SEC school was earning an estimated $54.3 million in conference payouts, while each Big 12 school was earning just an estimated $40.6 million (Navigate, 2022).

Texas and Oklahoma also offered significant value to the SEC in return. Since the College Football Playoff system began in 2014, Oklahoma and Texas were the most competitive teams in the Big 12, with the Sooners making the playoffs four times. Their states also had five of the top 50 television markets in the United States: Dallas-Fort Worth, Houston, San Antonio, Oklahoma City, and Austin (Station Index, n.d.). The SEC recognized the opportunity to bring in two more championship-caliber programs that both had rich winning traditions and extremely loyal fans when they extended them an invitation to join. With the addition of these two programs, the SEC’s projected conference payout increased from $54.3 per year per school in 2022 to $105.3 million in 2029, which was expected to outpace all the other Power 5 conferences (Navigate, 2022).

In college football, the five most competitive FBS conferences over most of the last three decades, the SEC, the Big Ten, the ACC, the Big 12, and the PAC 12, have been referred to as the “Power 5” conferences. The other five FBS athletic conferences, the American Athletic Conference (AAC), Conference USA (CUSA), the Mid-American Conference (MAC), the Mountain West Conference (MW), and the Sun Belt Conference, are referred to as the “Group of 5” or “G5” conferences.

In February of 2023, Texas and Oklahoma reached an early exit agreement with the Big 12 to allow them to join the SEC a year early. As part of the agreement, the schools would pay a combined $100 million in early withdrawal fees to the Big 12, plus an undisclosed amount to Fox which owned the Big 12 football broadcast rights (Silverstein, 2023). In the schools’ estimation, they would make that money back by being part of the SEC a season earlier.

2.6. Mass Exodus from the PAC 12

The defection by Texas and Oklahoma caused a ripple effect across college football, affecting even the lower levels of the sport. Out west, the leadership of the top PAC 12 programs—Oregon, Washington, USC, and UCLA—recognized that they could also benefit by joining the Big Ten, which would increase their annual media rights intake by $20 million. This would also allow their teams to play away games in more heavily viewed time slots. PAC 12 home games had usually been broadcast during the latest Saturday time slots which would end late in the evening for Eastern Time Zone viewers, thus substantially hurting their ratings and in turn, their ability to recruit top athletes.

The departure of Washington, Oregon, UCLA, and USC put the rest of the PAC 12 into panic mode, prompting the University of Arizona, Arizona State University, the University of Colorado, and the University of Utah to all leave for the Big 12. Stanford University and the University of California-Berkeley initially didn’t have a landing spot, but with the help of some lobbying by the University of Notre Dame’s athletic director, Jack Swarbrick, eventually ended up joining the ACC. This left Washington State and Oregon State behind in what is now called the “PAC 2,” an unofficial conference, because it is below the NCAA-mandated 8-team minimum league. Washington State and Oregon State are effectively now independents despite still flying the PAC 12 flag. It also resulted in the Power 5 conferences now becoming the Power 4.

2.7. Full-Scale Conference Realignment Chaos

In response to the defections by Texas and Oklahoma, the Big 12 recruited independent Brigham Young University (BYU) and three “Group of 5” schools from the American Athletic Conference (the University of Central Florida, the University of Cincinnati, and the University of Houston) to join their conference (Adelson, 2022).

Further conference realignment impacted the G5 conferences as Southern Methodist University (SMU) left Conference USA to join the ACC (Straka, 2023). This motivated the Conference USA and the Sun Belt Conference to recruit Football Championship Subdivision (FCS) schools to fill their leagues. The ripple effect then caused conference realignment within the FCS as well (Becton, 2025).

All of these conference changes occurred between 2021 and 2023, but more are being expected. The remaining PAC 12 universities, Washington State and Oregon State, are working to reestablish the league as an official NCAA conference by bringing in schools from the neighboring G5 conference, the Mountain West, including a playoff team this past season in Boise State University. They also plan to add FCS schools, UC Davis and Sacramento State, for all sports including football, as well as Gonzaga for basketball.

The Mountain West is responding by poaching schools from other Group 5 conferences. They have already added the University of Hawaii and University of Texas-El Paso (UTEP), as well as Grand Canyon University for non-football sports, and are looking to include Northern Illinois and Toledo from the MAC (Murray, 2024).

All this conference realignment has resulted in the emergence of four extremely large, influential, and lucrative “Power 4” athletic conferences. The Big Ten now has 18 full members despite its name. The ACC also has 18 members (though one of its members, Notre Dame, is not a football member). And the SEC and Big 12 (also contrary to its name) now have 16 full members. This gives these conferences increased power and influence relative to the NCAA and relative to the other small conferences, particularly in terms of striking television deals and pursing other revenue opportunities such as guaranteeing themselves playoff and bowl game spots.

Universities will likely continue to try to join the conferences with the best media contracts in order to make the most money. In a new development, Florida State University (FSU) and Clemson University have sued their conference, the ACC, as they openly have threatened to move elsewhere (Pool, 2025). Previously, schools have usually only left their old conference when their grant-of-rights agreements which cover their media deals have expired. Now some universities have filed lawsuits to break those agreements to be able to leave their conference without paying the contractual exit fees, which for FSU would be a $572 million buyout, and for Clemson would be a $140 million payment to the ACC (Carter, 2025).

2.8. Impact on Rivalry Games

One unfortunate consequence of conference realignment is it is difficult, if not impossible, for historic rivals to continue competing on an annual basis. College football has some historic cross-conference rivalries, many of which started when the teams played in the same conference. For example, the University of Florida (SEC) and Florida State (ACC) play in the Sunshine Showdown every fall. The University of South Carolina (SEC) and Clemson (ACC) play in the Palmetto Bowl. And the University of Georgia (SEC) plays Georgia Tech (ACC) in the annual game nicknamed “clean, old-fashioned hate” (Duffley, 2021). But one of the consequences of larger conferences is that its members are required to play more in-conference opponents, leaving fewer out-of-conference opportunities to continue these rivalries once one of the teams leaves their historic conference. Some athletic conferences are now requiring their members to play up to nine conference opponents each football season, leaving just three out-of-conference games on their members’ regular season schedules. Virtually all Power 4 teams will schedule one of their games against an FCS “cupcake” and one or two weaker G5 opponents, hoping for easy wins where they can rest their star players before a big in-conference game. This leaves at most one game per season for a team to schedule an out-of-conference game against a traditional rival.

In addition to the three SEC vs. ACC traditional rivalries listed above, six other annual games considered as recently as 2021 as part of “the 25 Biggest Rivalries in College Football” by FanBuzz are seriously threatened by conference realignment (Duffley, 2021):

- Notre Dame (Independent with ACC game commitments) vs. USC (Big Ten)

- Oklahoma (SEC) vs. Oklahoma State (Big 12) in “Bedlam”

- Washington (Big Ten) vs. Washington State (PAC 12) in “the Apple Cup”

- West Virginia (Big 12) vs. Pittsburgh (ACC) in “the Backyard Brawl”

- Kentucky (SEC) vs. Louisville (ACC) in “the Governor’s Cup”

- Oregon (Big Ten) vs. Oregon State (PAC 12) in “the Civil War”

Not surprisingly, all of these top rivalry games generate more fan interest, and correspondingly, higher television ratings and ticket sales than typical football games. The resulting loss of tradition undermines an important aspect of fan loyalty, where it is often just as important to root against a hated rival as cheer for one’s team.

3. The Transfer Portal

3.1. Founding of the National Collegiate Athletic Association

In 1906, the NCAA, was founded “to regulate the rules of college sport and protect young athletes” (NCAA, 2021). Today, the NCAA has 1,100 member schools, and over 500,000 student-athletes compete in events and games regulated by the NCAA every year (NCAA, 2021).

The NCAA establishes and enforces regulations regarding how student-athletes can transfer from one college to another. In the interest of promoting fair competition between schools, the NCAA has strived to allow students to transfer between programs while preventing coaches or other individuals from interfering or tampering with other programs by poaching their players. The NCAA historically accomplished this with a combination of transfer procedures that were long, tedious, and required multiple approvals, with disincentives to transferring in the form of eligibility penalties, and with sanctions against any program found to have illegally recruited a player from another program. The consequence of these procedures and penalties was that many student-athletes with legitimate reasons for wanting to transfer were either prohibited or dissuaded by the process.

3.2. Creation of the Transfer Portal

So, on October 15, 2018, the NCAA launched the transfer portal as a tool to streamline the transfer process and make it more transparent and equitable. For a student-athlete who felt that they would benefit from a change in schools, they could enter their name in the transfer portal during certain specified periods during the year, and other schools would be allowed to contact and recruit them (Johnson, 2019).

But initially it also came at a price to transfer, as they had to sit out for a year, and their current coach would have to approve the transfer. However, for many, the new system paid off. Players like Baker Mayfield, Kyler Murray, and Joe Burrow were able to win the Heisman Memorial Trophy after transferring to new schools that better utilized their talents.

Over time, the NCAA eliminated many of the approvals and penalties associated with transferring (NCSA, n.d.). It removed the rule that a player’s coach needed to approve their transfer. It also withdrew the requirement that a transferee needed to sit out for a year while losing a year of eligibility after their first transfer, retaining it for just subsequent transfers (Schad, 2023). And even those penalties for multiple transfers went away in 2024, after a coalition of state attorneys general challenged them in a lawsuit against the NCAA, and a judge issued a temporary restraining order supporting the plaintiffs (Associated Press, 2024).

3.3. Transfer Portal Windows

The transfer portal still has some unintended consequences that need to be addressed. One is related to the current transfer portal windows for college football. Currently, the first window is in December after the conclusion of the regular season, and the second window is in April, following spring practices (Nakos, 2024). The April window gives players who were expecting a bigger role with their current team a second chance to transfer if their expectations weren’t met during spring workouts. Initially the two windows were open for a total of 45 days—four weeks in December and two weeks in April. But after coaches requested shorter windows, the NCAA Division I council voted in October 2024 to reduce them to a total of 30 days for the 2024-25 cycle—three weeks in December and 10 days in April (Hummer, 2024). However, there is still heavy pushback against this two-window structure by coaches and others, because of the instability it brings to college football.

Football coaches have issues with the December window, because it is during bowl season. The nature of bowl season has changed dramatically with the adoption of a college playoff system. Teams that make the playoffs used to be able to readily expect their full rosters to play in those games. But with the non-starters wanting to avoid injury prior to transferring, their participation is uncertain. In the 2024 season, Penn State played its two playoff games without backup quarterback Beau Pribula, after he entered the transfer portal in December. Despite not being the starter, Pribula was an important contributor to Penn State’s offense as a running quarterback, playing in all but one game during the regular season. And for teams playing in non-playoff bowl games, coaches can anticipate that many of their players hoping to be drafted by the NFL will opt out of playing to avoid injury. Initially, only draft-eligible players were opting out, but now players in the transfer portal are also forgoing playing in bowl games. Marshall University had so many players decide to forego their bowl game after a successful 2024 season, that they had to decline the invitation (Hale, 2025. All of these developments are turning bowl teams into a fraction of their regular season self and dramatically reducing the economic value of those bowl games (Rumsey, 2023).

Roster stability in December is now in total chaos for coaches as they try to prepare for bowl games by dealing with these draft opt-outs, players on their roster likely entering the portal, preparing young players that are replacing those not playing, all while having to recruit potential incoming transfers. National Signing Day for high school players is also right around this time making it the craziest time of the year for college coaches. Pushing the portal window back would help stabilize their roster for their bowl game and delay worrying about recruiting incoming transfers.

The spring portal window also poses a problem for roster stabilization, because by April coaches want their rosters to be set. Losing a key player this late in the off season does not give a lot of time to find a replacement.

In a statement to ESPN, SMU head coach Rhett Lashlee points out that the transfer portal needs to be built around the academic calendar. He says, “We want to protect the season and the sanctity of that, but at the same time, you’re trying to fit a competitive or an academic calendar to sync up, that’s a challenge… We’re the ones on the ground and we know the problems and probably the best solutions, so to be all on the same page and come to a consensus on what the best path forward is, I think we did that” (Hale, 2025).

At the 2025 American Football Coaches Association Convention, FBS coaches unanimously approved changing to a single 10-day transfer portal window in January, eliminating the December and April windows (Marcello, 2025). But student-athletes, for the most part, oppose this potential ruling, because it removes their option for entering the transport portal after seeing where they land on their team’s depth chart after spring practices.

3.4. Unanticipated Developments

The transfer portal has significantly altered how college football coaches recruit athletes and manage their rosters. Coaches now monitor the portal closely looking for experienced players who can contribute immediately. They often look to recruit players from rival programs to give them a competitive advantage. And with a limited number of scholarships available, college programs must weigh the risks of recruiting unknown high school athletes versus proven players in the portal.

Another even larger issue with the transfer portal is how NIL has created additional unanticipated incentives for students to transfer undermining fan loyalty and resulting in far less roster stability than is healthy for the sport.

According to NCAA transfer data, in the first full year of the transfer portal, the 2018-19 cycle, 1,561 FBS players transferred. Six years later during the 2023-24 cycle, the number of FBS transfers had increased by 140% to over 3,700, many in search of NIL deals (NBC Sports, 2025). 883 of those players transferred to a Power 4 school, almost twice the 454 from a year earlier (Marler, 2024). And more than 11,000 NCAA football players across all divisions entered the portal during the 2023-24 cycle. (NBC Sports, 2025).

The impact on roster stability has been devastating. In 2020, 10.7% of FBS starters were transfers, while two years later, that number had nearly doubled to 20.9%, according to SportSource Analytics (Van Haaren, 2022). 72 FBS teams lost 20 players or more to the portal in 2024, nearly triple the number from 2022. 29.7% of the top 100 recruits over the 2021, 2022, and 2023 seasons have entered the transfer portal at least once in their career (Nakos, 2024). Over 60 FBS teams had a transfer quarterback on their roster in 2024 (Marler, 2024). This high roster turnover has negatively impacted team dynamics, making it more difficult for programs to develop the needed chemistry between players and coaches.

Twenty-five percent of freshman Division I football players are entering the portal, demonstrating a startling lack of patience and commitment to the schools that recruited them out of high school. This is forcing coaches to consider playing these players earlier in their development than they would otherwise or risk losing them. Even more concerning is that 30% of the players who enter the portal neither transfer nor return to their current school—it’s important to remember that once an athlete enters the transfer portal, their current school has no obligation to welcome them back if the player changes his mind. If a college football player doesn’t transfer or return to their current team, their only options are to enroll at and play for a junior college, stop playing football all together, or hope to be signed by a professional team (Marler, 2024). These data points suggest that a large percentage of college football players are overestimating the benefits and underestimating the risks of entering the transfer portal.

4. Name, Image, and Likeness

4.1. Impermissible Payments

Cases of college athletes being paid illegally to play their sport are almost as old as college sports itself. Players have always desired to make money, and coaches and fans have often been willing to break the rules and pay star athletes to play for their teams. Over the decades, the problem has grown as college sports have generated exponentially more money, increasing the funds available for impermissible payments as well as the rewards for gaining a competitive advantage. Student-athletes not being allowed to be paid legally also gained the public’s attention as virtually everyone else involved with college athletics—the universities, the coaches, the athletic conferences, the NCAA, and the media companies—have enriched themselves, while the athletes have been left out of sharing the huge profits resulting from their contributions.

A watershed event occurred in 1987, when SMU was given the “death penalty” by the NCAA, cancelling their entire football season for a year, loss of scholarships, and imposing other penalties for repeated violations of the association’s rules against paying recruits and players. The NCAA said that their investigation revealed a program “completely out of control.” The reason that SMU’s coaches, athletic staff, and boosters repeatedly violated those rules is because it enabled them to recruit and retain an extremely talented roster that produced some of the most successful seasons in SMU’s history (Dodds, 2015).

The penalties had a devasting impact on SMU’s football program. After resuming play in 1989 (SMU self-imposed an additional year of not playing football), SMU had a winning record just once in the subsequent 21 seasons. The public spectacle of the investigation and penalties also placed a cloud of suspicion and distain for the entire SWC, leading to the mass exodus of other teams and its eventual disbandment after the 1995 season (Fertak, 2023).

Even after the severe penalties the NCAA imposed on SMU, other programs continued to pay their recruits and players illegally, usually being more creative and careful to not get caught. In 2010, after a four-year investigation, the NCAA imposed severe sanctions on the USC football program for “lack of institutional control” that allowed their star running back, Reggie Bush, to be paid illegally during the 2004 season. USC lost 30 scholarships over three years, received a two-year post-season ban, and had to vacate all of their wins during the 2004 season, including their Orange Bowl victory that won them the BCS National Championship (ESPN, 2010). Reggie Bush would voluntarily forfeit his Heisman Trophy that he won during that season (Hiserman, 2010).

But even with another major scandal, illegal payments to players continued to be uncovered. In 2021, it was reported that the University of Tennessee was caught giving recruits cash in McDonald’s take-out bags (Conway, 2021).

4.2. Establishment of Name, Image, and Likeness

So in 2021, reacting to the pressure from groups advocating that student-athletes should be paid for their contributions, including many state legislatures, and to the desire to lessen the constant stream of scandals that were sullying the reputations of college athletics, the NCAA changed their rules to allow student-athletes to be paid for the Name, Image, and Likeness (NCSA, 2024). NIL has revolutionized college sports by allowing collegiate athletes to be compensated for their play through brand deals, merchandise, and team-wide endorsement deals. However, schools are not allowed to directly pay these athletes; those payments are made through NIL collectives. Collectives are third-party entities that organize the NIL deals between companies and the athletes who advertise the companies’ product or services.

4.3. Early Concerns

While many are happy that student-athletes can now be able to be compensated for the notoriety they create playing college sports, not everyone is pleased with the development. Consistently across multiple surveys since NIL was implemented, college athletic directors have expressed concerns about NIL. In a survey of Division I athletic directors by the Associated Press, nearly 73% of respondents share that “allowing athletes to be compensated for NIL use will decrease the number of schools that have a chance to be competitive in college sports.” Almost 28% responded that “many fewer schools would be competitive” (Russo, 2021).

In a 2022 survey conducted by LEAD1, 90% of athletic directors are concerned that “NIL payments from collectives are being used as improper recruiting inducements, both for high school prospects and transferring players,” with 73% saying they are “extremely concerned.” 77% responded that they believe an “unregulated NIL market will lead to more scandals” (Lead1 Association, 2022).

And a survey by Athletic Director U found that 46.9% of responding athletic directors do not “support student-athletes have the opportunity to be compensated for commercial use of the Name, Image, and Likeness.” Interestingly, 57% of Power 4 athletic directors support NIL in some form, while 67% of Group of 5 ADs support it, and just 43% of FCS directors (AthleticDirectorU, n.d.).

4.4. Lack of Regulations

This new NIL era of college football is being referred to as the “Wild West” due to the lack of rules. An ESPN article in January of 2022 highlighted the challenge of determining what activities cross the line. According to the Associated Press, “The deals are being done with third parties. And the NCAA has no jurisdiction over those third parties, said Mit Winter, a former college basketball player and now a sports law attorney for Kennyhertz Perry.’ ‘[The NCAA] can talk to and gather information from schools and the athletes. But any incriminating information is most likely going to be among people that either for or have some involvement with third parties” (Russo, 2022).

However, accusations of college coaches trying to lure or retain athletes to their program using promises of NIL deals are now being litigated in court. Six players from FSU’s 2023-2024 men’s basketball team have filed a lawsuit against long-time head coach Leonard Hamilton claiming that they were each repeatedly promised NIL payments of $250,000 that were never made. Interestingly, the plaintiffs say the coach made the promises on behalf of his “business partners” that that the players never met directly, instead of through a collective. The allegation of this direct involvement by the coach would appear to be a violation of current NCAA NIL rules (Sabin, 2024).

4.5. The Monetary Impact of NIL

In 2024, the top fifteen football NIL collectives spent an estimated $200 million, with that year’s National Champion Ohio State’s two collectives, 1870 Society and The Foundation, topping the list spending a combined $20 million on the Buckeye’s roster (Nakos, 2024).The NCAA estimates that the top 25 college football collectives received between $9.3 million and $22.2 million each from fundraising and donations (Crawford, 2024).

For football players, the NIL deals can be comparable to what they could earn in the NFL. Tulane redshirt freshman quarterback, Darian Mensah, has reportedly signed a two-year NIL deal worth a record $8 million for transferring to Duke after entering the transfer portal in December 2024 as just the seventh-ranked QB in the portal. With three years of eligibility, Mensah will be negotiating a new NIL deal with Duke’s collective or someone else for the 2027 season (Mader, 2024).

The NCAA has made attempts to limit NIL but has been stymied by the courts (Associated Press, 2024). Most notably, in the case State of Tennessee v. NCAA,the judge ruled the NCAA’s stance violated antitrust laws regarding NIL (Walker & Russo, 2024) (Walker, 2025).

4.6. Direct Payments from Universities to Students

Separately, in May of 2024, the NCAA and the former Power 5 athletic conferences agreed to pay $2.75 billion to 14,000 former collegiate athletes to settle an antitrust class action. In House v NCAA the college athletes who were enrolled between 2016 and 2020 sued over lost opportunities and profits prior to the NCAA adopting NIL in 2021. The settlement is still winding through the judicial approval process, but the parties expect that a federal judge will sign off on it in April of 2025. The terms of the agreement are that the NCAA will pay $110 million per year over the next 10 years deducted from the payments it gives to universities from profits on TV and merchandising deals. The 57 universities that made up the Power 5 will pay the remaining $1.65 billion to their respective former students. The agreement also states that the universities will share 22% of the revenue from their media rights deals with athletes going forward—an amount currently equal to about $20 million per year. (Athletes in the NFL and NBA receive approximately 50% of their respective leagues’ media-related revenues.) It’s expected that non-Power 5 schools will be able to opt-in to this revenue sharing to avoid being at a competitive disadvantage for attracting athletes to their schools. The form, timing, and distribution among students and sports programs of these payments from the universities to the athletes still need to be defined. As these details are decided, expect major changes in who (i.e. universities, collectives, and boosters) and how (i.e. direct payments, NIL deals, or other business arrangements) college athletes are compensated (Webster & Paulsen, 2024).

4.7. Collective Bargaining Agreements as a Possible Solution

One advancement that might help both the NCAA and student-athletes is if they could agree on a collective bargaining agreement (CBA), similar to the ones used in professional sports. CBAs are deals between a sports league and the athletes playing for the league that set out all the rules and conditions of employment and need to be agreed upon by both sides. Usually, a part of the agreement is a salary cap that limits teams from gaining an advantage by massively outspending their competition. Establishing a salary cap for NIL deals could be an element for effective NIL regulation to promote a level playing field among university athletic programs (NBA & NBPA, 2023) (NFL & NFLPA, 2020).

However, there are reasons for both the NCAA and student-athletes that might lead them to not support a CBA. For the athletes, at this point, the only limit on the amount of money they can earn from NIL deals is the number of years of eligibility the NCAA grants them. And even then, Diego Pavia, Vanderbilt’s starting quarterback won a lawsuit against the NCAA giving him an extra year of eligibility. That additional season of football is expected to allow him to earn up to an extra $1 million of NIL money (Boyer, 2024). So for athletes to agree on limiting the amount of money they can make in a given year, they will want to receive something else in return, such as additional years of eligibility. As for the NCAA, a CBA would essentially recognize student-athletes as professional players and employees with all the issues of unionization and employee rights that they have been adamant on avoiding (Associated Press, 2024). Additionally, the task of organizing the college athletes in a player’s association would be very difficult. Most professional leagues have a few hundred athletes, all playing the same sport. None of them have anywhere close to the 500,000 athletes playing in 90 different sports that are governed by the NCAA (NCAA, 2021).

A simplified approach is for student-athlete associations and CBAs to be created for each individual NCAA sport. The number of athletes per association would still be significantly more than in professional leagues, but at least it would be more manageable. Also, these CBAs could be tailored to the unique requirements and characteristics for each sport and their student-athletes. For example, college sports such as football and tennis have significantly different practice and competition schedules as well as travel requirements and generate vastly different levels of revenue both for the universities and for the athletes through NIL deals.

4.8. Combined Impact of NIL and the Transfer Portal

In addition to the challenges to competitive balance created by the current NIL regime, as noted in the LEAD1 survey of athletic directors, when combined with the transfer portal, an environment has emerged where programs are using NIL deals to entice student-athletes to transfer to their programs. For outstanding players at schools with less exposure, there have always been incentives to transfer to raise their potential draft stock. But prior to NIL, the (legal) monetary benefit to transferring to a bigger program was always indirect. With NIL, the benefits for transferring are more immediate and less speculative. So, it is the top-tier programs supported by wealthy NIL consortiums that attract top talent from other schools, creating a dynamic where the top schools become even better, and the rest fall further behind.

As one example of this phenomena consider wide receiver Devonte Ross. In 2024, Ross had an exceptional season for Troy University, recording 76 catches for 1,043 yards and 11 touchdowns. Shortly after the season ended, Ross entered the transfer portal and committed to Penn State, one of the premier programs in college football (Pickel, 2024). This illustrates how competing at a high level against Power 4 schools as a G5 team is becoming more difficult as they lose the off-field battles to retain their best talent and recruit elite players.

Even among Power 4 programs, teams are finding that their collectives need to increase the amount they pay their athletes after a standout year in order to keep them from transferring to another program. After winning the national championship in 2024, it’s been reported that Ohio State’s two best wide receivers with remaining eligibility, Jeremiah Smith and Carnell Tate, were offered over $4.5 million and $1.0 million respectively to enter the transfer portal, triggering accusations of illegal tampering (Nakos, 2025). To circumvent that type of tampering, the University of South Carolina’s NIL collective, Garnet Trust, offered the school’s outstanding freshman pash rusher, Dylan Stewart, a new NIL deal worth between $1.0 million and $1.5 million to keep him with the Gamecocks (Joyce, 2024).

4.9. Title IX’s Applicability to NIL

One additional issue with NIL is whether it should be subjected to Title IX restrictions. Title IX is a landmark civil rights amendment to the Higher Education Act of 1965 which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in educational institutions receiving federal aid, ensuring equal rights for women and equal funding for all educational programs, including all NCAA sports. The rule is interpreted as requiring schools to give out proportional amounts of scholarship funding to men and women, according to their student population (U.S. Department of Education, 2021).

But with the emergence of NIL, the question is being asked whether NIL payments also need to be proportional to comply with Title IX. So far, college football and men’s basketball players have earned the most NIL money. But as of now, NIL deals are paid by third parties, not the universities, placing them outside the jurisdiction of Title IX. However, a pending court settlement that is likely to be approved will allow athletes to get paid directly from their schools starting in the 2025-2026 season (Conrad, 2024). According to an official from the U.S. Department of Education, the future revenue share that goes to athletes will have to comply with Title IX. The department didn’t offer any guidance on how to do this (Lavigne & Murphy, 2025). Sharing the revenue equally, when the produced income isn’t even close to equal, may prove to be a challenge for college athletic departments.

If Title IX does not apply, the overwhelming majority of payments will continue to go to football and men’s basketball teams, because they are the programs generating revenue for the university. But if it’s ruled that Title IX does apply, schools will need to split the money (based on the proportional amounts for student population) between men’s and women’s programs. So within men’s programs, the money can still go mainly to the two big sports, but schools would be operating with only half the money for football and basketball, while supporting women’s programs.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

It is clear there are (at least) three major problems in college sports that need solutions: athletic conference realignment, the current state of the transfer portal, and NIL. However realistic fixes to these issues are less clear.

The issue of conference realignment is something that the NCAA has limited power to control. They can’t force teams to join or to stay in a conference; that is controlled by contractual relationships between the universities and their conference. The only real influence the NCAA has is requiring a school to meet certain requirements if they want to change divisions as part of switching conferences.

If the NCAA ever tried to force schools to join or remain in a specific conference, there could be a mass exodus of schools leaving the NCAA. The NCAA presently needs to be concerned about that, as the Power 4 conferences are becoming large and powerful enough that they could agree upon how their schools compete without NCAA oversight at all. If conference consolidation continues to reduce the number of athletic conferences, the threat to the NCAA will continue to grow.

One solution that could address problems with both NIL and the transfer portal is a cap on the amount of NIL money that can be raised and distributed per university or university team. Figuring out an agreed level would be difficult and may need to be adjustable based on inflation and the changing amount of revenue generated by each sport. College administrators should make it a top priority to investigate establishing an NIL “salary” cap covering all schools in a division. Instituting one could help stabilize the transfer portal and lead to less illegal tampering.

Additionally, an NIL cap would support competitive parity in college football. As previously mentioned, the top two NIL spenders in college football this season were Texas and Ohio State (Crawford, 2024). This year, Ohio State won the national championship, defeating Texas in the CFB Semifinal. For the most part, the rest of the playoff field was not far behind in terms of NIL spending. This shows that college football success is highly correlated with NIL spending, much like how success in Major League Baseball is highly correlated with the amount a team spends on player salaries given the league doesn’t have a salary camp. Last year, three of the four teams with the highest salary expenditures—the New York Yankees, the New York Mets, and the Los Angeles Dodgers—were three of the four semifinalists, including the eventual World Series Champion, the Dodgers (Spotrac, 2025). If the NCAA doesn’t implement a salary cap, it could follow the path of professional baseball where the richest teams dominate the poorer, smaller market teams by regularly poaching their talent.

But before a salary cap can be established, a collective bargaining agreement would need to be agreed upon by the players, the universities, and the NCAA. Most likely separate CBAs would govern each individual NCAA sport. The CBAs would also probably require NIL deals to be made by the universities directly, instead of through collectives, triggering adherence to Title IX. So, because of the challenges of establishing these CBAs, implementing a salary cap is unlikely to happen soon, so the schools with the best funded collectives will continue to dominate for the foreseeable future.

Title IX’s application to college sport scholarships has already been criticized for forcing universities to eliminate men’s programs (or “demote” them to non-NCAA club programs) in order to achieve proportional equity with women’s sports. Part of the problem is that only men play college football, and because of the large rosters and the full scholarships in football, it requires several women’s teams to balance the scholarship numbers and dollars of the football team, leaving none for other men’s sports. One proposal has been to not include football in the proportionality calculations, since it is unique to men. That would allow more men’s programs to exist. It would also make it easier for universities to take over NIL payments from collectives and be able to abide by Title IX proportionality restrictions.

Beyond supporting CBAs, the NCAA has basically three tools to address the current problems with the transfer portal.

First, it needs to crack down more heavily on cases of illegal tampering. Illegal tampering is an open secret with sports news outlets publishing a stream of stories of players not in portal being offered millions of dollars to transfer. Yet few of the schools involved are ever punished.

Second, it needs to consider reinstituting the rules that limit the number of times a student can transfer and possibly reimpose the penalty that the athlete loses a year of eligibility when they do change schools. These former rules increase the costs to the player of transferring. Reinstituting them would result in student-athletes needing to be more certain on the benefits of transferring before doing so. Freshmen, in particular, would have greater motivation to stay with their current school, even if they don’t play their first year.

Instead of reinstituting the former rules, an alternate approach could be to regulate NIL deals, so that the terms of agreements only allow a player to receive compensation after being with a school for two years. This is analogous to multi-year contracts in professional sports and would greatly decrease the frequency of athletes transferring after a single season. However, given the NCAA’s track record in the courts, having a student-athlete representative body agree to these restrictions is almost certainly required.

Third, the NCAA needs to do a much better job of communicating to student-athletes the risks involved with both entering the transfer portal and transferring schools. The media disproportionately highlights the success stories of players transferring but doesn’t find most of the stories of bad decisions and derailed college careers as newsworthy. So, the NCAA has a responsibility to make sure that before a student-athlete enters the transfer portal, they fully understand the risks involved.

The combination of all these actions will hopefully bring needed stability back to college football rosters.

Tradition and fan loyalty have always been two of college sport’s greatest assets. Fans want to cheer for their alma mater, their hometown team, or their home state university, as well as root against their school’s rivals. Historically, tradition and loyalty have been fueled by the stability of college teams where athletes typically played for the same school their entire college career, and athletic conferences would foster rivalries by scheduling the same matchups year after year. Tradition and fan loyalty were college sports’ competitive advantages against professional sports, where despite generally having superior athletes, loyalty and tradition are harder to instill as athletes constantly switch teams through free agency and trades, and franchises move to new cities with some frequency, often changing their team names.

The biggest economic threat to college sports in general, and college football in particular, is this new era where that stability has been erased. College players increasingly no longer show loyalty to their teams and its fans as they are willing to jump into the transfer portal in search of more playing time and a more lucrative NIL deal. In possibly the most striking example of how player loyalty is being undermined by NIL and the transfer portal, on the final weekend of September in 2024, the starting quarterback of the 3-0 University of Nevada—Las Vegas (UNLV), senior Matthew Sluka, announced that he would not play any more games for the team that season, claiming the school never paid him the $100,000 they promised him in a NIL deal. On College GameDay, host Rece Davis commented, “Going in there and expecting something without writing, and then they don’t give it to you, you can’t just bail on the team.” (Kirshner, 2024). Months later, Sluka, who started his career playing for Holy Cross before transferring to UNLV, was visiting FBS schools Memphis and Liberty in search of a new team (Lyons, 2024).

It is difficult for fans to show loyalty to players who don’t reciprocate. And traditional rivalries are increasingly coming to an end as teams switch conferences or are no longer able to schedule the same teams every year in “super-sized” conferences. If these trends continue, college sports may lose the primary drivers for fan loyalty, attendance, viewership, and memorabilia purchases, further transforming them into farm programs for professional sports.

If college athletics wants to stay competitive with the other top sports in America, they must stay true to the traits and values that caused so many fans to fall in love with the game of football.

Acknowledgements

Porter McAndrews thanks Dr. Nikolas Webster, Assistant Professor of Sports Management at the University of Michigan, for mentoring and advising him during the writing of this research paper.

References

Adelson, A. (2022, June 22). Cincinnati, Houston, UCF reach exit deal with American, to join Big 12 in 2023. ESPN. https://www.espn.com/college-sports/story/_/id/34069597/cincinnati-houston-ucf-reach-exit-deal-american-join-big-12-2023

Associated Press (2024, April 22). NCAA ratifies immediate eligibility for athletes no matter how many times they switch schools. https://apnews.com/article/ncaa-transfer-rule-nil-changes-b980ee3231b5c124e344da2719ee39c9

Associated Press (2024, May 23). The NCAA has agreed to settle a major lawsuit. It still faces a number of legal challenges. https://apnews.com/article/ncaa-legal-problems-fe7bce9289ac1a017c3ad3bcc9f1ee8e

AthleticDirectorU (n.d.). What Do Athletic Directors Think About Name, Image and Likeness? https://athleticdirectoru.com/articles/what-do-athletic-directors-think-about-name-image-and-likeness/

Becton, S. (2025, February 16). Making sense of FCS conference realignment. NCAA https://www.ncaa.com/news/football/article/2025-02-16/making-sense-fcs-conference-realignment

Bigalke, Z. (2018, January 7). A brief history of conference affiliation in college football. Saturday Blitz. https://saturdayblitz.com/2018/01/07/smq-brief-history-conference-affiliation-college-football/

Boyer, C. (2024, December 24). Diego Pavia Explains Lawsuit Against NCAA, Tells of Positive NIL Impact. Sports Illustrated. https://www.si.com/fannation/name-image-likeness/nil-news/diego-pavia-explains-lawsuit-against-ncaa-tells-of-positive-nil-impact

Carter, D. (2025, January 30). Why new ESPN deal could keep Clemson, Florida State in ACC, help settle lawsuit. Greenville News. https://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/sports/college/clemson/2025/01/30/clemson-florida-state-acc-espn-tv-contract-lawsuit/78053164007/

Cesconetto, G. I. (2025, January 13). How many NCAA football players make it to the NFL? Sportskeeda. https://www.sportskeeda.com/college-football/how-many-ncaa-football-players-make-nfl

Conrad, E. (2024, December 3). Federal Judge Expected to Approve Settlement Allowing Schools to Pay Athletes. News On 6. https://www.newson6.com/story/674fd75a6bedc5da1ab12fbe/federal-judge-expected-to-approve-settlement-allowing-schools-to-pay-college-athletes

Conway, T. (2021, January 19). Dan Patrick: Tennessee Recruits Got Cash in McDonald’s Bags Amid NCAA Violations. Bleacher Report. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2927349-dan-patrick-tennessee-recruits-got-cash-in-mcdonalds-bags-amid-ncaa-violations

Crawford, B. (2024, December 12). College football NIL collective leaders for 2025: NCAA estimates nation’s top-25 spenders. 247Sports. https://247sports.com/longformarticle/college-football-nil-collective-leaders-for-2025-ncaa-estimates-nations-top-25-spenders-241949240/

Dodds, E. (2015, February 25). The ‘Death Penalty’ and How the College Sports Conversation Has Changed. Time. https://time.com/3720498/ncaa-smu-death-penalty/

Duffley, J. (2021, November 19). The 25 Biggest Rivalries in College Football, Ranked. FanBuzz. https://fanbuzz.com/college-football/top-25-rivalries-college-football/

Dufresne, C. (1996, August 27). Merger Creates Dynamite Dozen. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-08-27-sp-38013-story.html

ESPN (2010, June 10). NCAA delivers postseason football ban. https://www.espn.com/los-angeles/ncf/news/story?id=5272615

Fertak, A. (2023, July). The Break-Up of the Southwest Conference (Vol. 10, No. 3) Houston History Magazine. https://houstonhistorymagazine.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/SWC.pdf

Hale, D. (2025, January 14). FBS coaches support single, shorter transfer portal window. ESPN. https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/43413122/fbs-coaches-support-single-shorter-transfer-portal-window

Henry, K. (2023, August 13). A History of Conference Realignment. KLIN. https://klin.com/2023/08/13/a-history-of-conference-realignment/

Hiserman, M (2010, July 20). USC to send back its Reggie Bush Heisman. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/blogs/sports-now/story/2010-07-20/usc-to-send-back-its-reggie-bush-heisman

Hummer, C. (2024, October 30). College football transfer portal dates, rules: What you need to know ahead of CFB’s winter transfer window. 247Sports. https://247sports.com/article/college-football-transfer-portal-dates-rules-what-you-need-to-know-ahead-of-cfbs-winter-transfer-window-238885611/

Johnson, G. (2019, October 8). What the NCAA Transfer Portal Is… and What It Isn’t. NCAA. https://www.ncaa.org/news/2023/2/8/media-center-what-the-ncaa-transfer-portal-is-and-what-it-isn-t

Joyce, A. (2024, December 10). Dylan Stewart Signs New Collective Deal. Sports Illustrated. https://www.si.com/college/southcarolina/dylan-stewart-signs-new-collective-deal-01jerhkn1ab8

Kirshner, A. (2024, December 19). Why the College Football Transfer Portal Has Sparked an Existential Crisis. The Ringer. https://www.theringer.com/2024/12/19/college-football/college-football-transfer-portal-nil-matthew-sluka-james-franklin

Koppett, L. (1999). Baker Field: Birthplace of Sports Television. Columbia University. https://www.college.columbia.edu/cct_archive/spr99/34a.html

Lavigne, P. & Murphy, D. (2024, July 16). Title IX will apply to college athlete revenue share, feds say. ESPN. https://www.espn.com/college-sports/story/_/id/40567726/title-ix-college-athlete-revenue-share-nil

Lead 1 Association (2022, May 4). LEAD1 Survey Reveals 90% of FBS Athletic Directors Polled Are Concerned NIL Used as Improper Recruiting Tool. https://lead1association.com/lead1-survey-reveals-90-of-fbs-athletic-directors-polled-are-concerned-nil-used-as-improper-recruiting-tool/

Learfield (2021). Intercollegiate Fan Report 2021. https://cdn.learfield.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/LEARFIELD_Intercollegiate_Fan_Report_2021_Final.pdf

Lyons, D. (2024, December 17). Former UNLV QB Matthew Sluka Schedules Two FBS Visits Months After NIL Dispute. Sports Illustrated. https://www.si.com/college-football/former-unlv-qb-matthew-sluka-fbs-visits-nil-dispute

Mader, D. (2024, December 24). Darian Mensah NIL money, explained: Did Duke make Tulane transfer ‘highest-paid’ college football player ever? The Sporting News. https://www.sportingnews.com/us/ncaa-football/news/darian-mensah-nil-money-duke-tulane-transfer-highest-paid-cfb/da9e2856b36aa8abbd93188f

Mandel, S. (2014, June 18). The real reason the Big Ten added Maryland and Rutgers – survival. Sports Illustrated. https://www.si.com/college/2014/06/18/big-ten-expansion

Marcello, B. (2025, January 14). FBS coaches vote to shrink transfer portal window to 10 days, implement recruiting dead period in December. CBS Sports. https://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/fbs-coaches-vote-to-shrink-transfer-portal-window-to-10-days-implement-recruiting-dead-period-in-december/

Marler C. (2024, December 9). Transfer Portal By the Numbers. Louisiana Sports. https://www.louisianasports.net/transfer-portal-by-the-numbers/

Morones, S. & Heidt, P. (2023). Following the Money in College Sports. Morones Analytics. https://moronesanalytics.com/following-the-money-in-college-sports/

Murray, C. (2024, November 4). Who should be the Mountain West’s next addition in conference realignment? Nevada Sports Net. https://nevadasportsnet.com/news/reporters/murrays-mailbag-who-should-be-mountain-wests-next-addition-in-conference-realignment

NBA & NBPA (2023, July). Collective Bargaining Agreement. https://imgix.cosmicjs.com/25da5eb0-15eb-11ee-b5b3-fbd321202bdf-Final-2023-NBA-Collective-Bargaining-Agreement-6-28-23.pdf

NBC Sports (2025, January 7). College football 2025 transfer portal tracker. https://www.nbcsports.com/college-football/news/college-football-2025-transfer-portal-tracker

NCAA (2021, February 16). Overview. https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2021/2/16/overview

NCAA (2021, May 4). History. https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2021/5/4/history

NCAA (2024, November 8). College football championship history. https://www.ncaa.com/news/football/article/college-football-national-championship-history

NCAA (2025, January 20). College football history: Notable firsts and milestones. https://www.ncaa.com/news/ncaa/article/2025-01-20/college-football-history-notable-firsts-and-milestones

NCSA (2024, December 6). Name, Image, Likeness. https://www.ncsasports.org/name-image-likeness

NCSA (n.d.). NCAA Transfer Rules. https://www.ncsasports.org/recruiting/ncaa-transfer-rules

NFL & NFLPA (2020, March 15). Collective Bargaining Agreement. https://nflpaweb.blob.core.windows.net/website/PDFs/CBA/March-15-2020-NFL-NFLPA-Collective-Bargaining-Agreement-Final-Executed-Copy.pdf

Nakos, P. (2024, January 17). Nearly 30% of top-100 recruits since 2021 have entered transfer portal. On3. https://www.on3.com/transfer-portal/news/transfer-portal-30-percent-enter-top-100-prospects-recruiting-cycle-college-football/

Nakos, P. (2024, August 29). On3’s top 15 NIL collectives in college sports. On3. https://www.on3.com/nil/news/on3s-top-15-nil-collectives-in-college-sports/

Nakos, P. (2024, December 8). College Football Transfer Portal: Dates for winter, spring entry windows. On3. https://www.on3.com/news/college-football-transfer-portal-dates-winter-spring-entry-windows/

Nakos, P. (2025, January 24). Inside Ohio State’s bid to keep roster together for 2025. On3. https://www.on3.com/news/inside-ohio-state-buckeyes-bid-to-keep-roster-together-for-2025/

Navigate (2022, March 4). Power 5 Conference Payout Estimates. https://nvgt.com/blog/power-5-conference-payout-estimates/

New York Times (1920, December 11). New College Body Planned in South. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1920/12/12/112666051.pdf

Padilla, J. D. (2019, December 4). What is the Role of College Athletics, and Should Student-Athletes be Paid? Valparaiso University. https://www.valpo.edu/president/editorials/what-is-the-role-of-college-athletics-and-should-student-athletes-be-paid/

Perrin, M & Solomon, J. (2008, February 24). Southeastern Conference charter schools move on in different directions. AL.com. https://www.al.com/bn/2008/02/southeastern_conference_charte.html

Pickel, G. (2024, December 24). Penn State picks up transfer portal pledge from former Troy receiver Devonte Ross. On3. https://www.on3.com/teams/penn-state-nittany-lions/news/penn-state-picks-up-transfer-portal-pledge-from-former-troy-receiver-devonte-ross/

Pool, C. (2025, March 3). ACC Conference Realignment News: The Future of ACC Football Remains Uncertain. Hero Sports. https://herosports.com/fbs-acc-conference-realignment-news-college-football-florida-state-clemson-cpcp/

Reeves, R. (2024, July 13). The Most Watched College Football Games in U.S. TV History. Front Office Sports. https://frontofficesports.com/most-watched-college-football-games/

Rhodes, C. C. (2024, June 8). What’s the purpose of college athletics? Times West Virginian. https://www.timeswv.com/opinion/columns/column-whats-the-purpose-of-college-athletics/article_8face680-2500-11ef-be7e-5badb0464459.html

Richmond, S. (2023, November 6). 1st college football game ever was New Jersey vs. Rutgers in 1869. NCAA. https://www.ncaa.com/news/football/article/2017-11-06/college-football-history-heres-when-1st-game-was-played

Rumsey, D. (2023, December 16). The Problem with 43 Bowl Games? Meaning and Name Recognition. Front Office Sports. https://frontofficesports.com/newsletter/do-bowl-games-still-matter/

Russo, R. D. (2021, April 4). AP survey: ADs concerned NIL will skew competitive balance. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/ap-survey-ads-concerned-nil-will-skew-competitive-balance-65b34bf310b0c4fa2fa123ed4b3ba87d

Russo, R. D. (2022, January 29). Lack of detailed NIL rules challenges NCAA enforcement. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/college-football-sports-business-15e776b5d115dac0a37a1563d5bfce00

SEC Sports (2023, April 4). SEC History. https://www.secsports.com/news/2023/04/sec-history

Sabin, J. (2024, December 31). What The NIL Lawsuit Against FSU Head Basketball Coach Means. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/joesabin/2024/12/31/breaking-down-the-nil-lawsuit-against-fsu-head-basketball-coach/

Schad, T. (2023, November 29). NCAA transfer portal, explained: What it actually is and how it works in college football. USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/ncaaf/2022/12/15/ncaa-college-football-transfer-portal-explained/10889658002/

Silverstein, A. (2023, February 9). Texas, Oklahoma leaving Big 12 early, joining SEC in 2024 season after reaching exit agreement. CBS Sports. https://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/texas-oklahoma-leaving-big-12-early-joining-sec-in-2024-season-after-reaching-exit-agreement/

SoCon (2024, June 1). Conference History. https://soconsports.com/about/general/conference-history/

Spearman, T. (2016, November 22). The Rivalry in Dixie: Hatred Renewed. SB Nation. https://www.underdogdynasty.com/2016/11/22/13695474/the-rivalry-in-dixie-hatred-renewed-louisiana-tech-bulldogs-southern-miss-golden-eagles-cusa

Sports League Maps(2024, May 18). Big Ten Map. https://sportleaguemaps.com/ncaa/big-ten/

Sports Reference (n.d.). SRCFB Conference Index. https://www.sports-reference.com/cfb/conferences/

Spotrac (2025). MLB Team Salary Payroll Tracker/2025. https://www.spotrac.com/mlb/payroll/_/year/2025/sort/players_active_avg_age/dir/desc

Straka, D. (2023, September 1). SMU joins the ACC: How the Mustangs rose from the death penalty to an improbable return to a major conference. CBS Sports. https://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/smu-joins-the-acc-how-the-mustangs-rose-from-the-death-penalty-to-an-improbable-return-to-a-major-conference/

Station Index (n.d.). Top 100 Television Markets. https://www.stationindex.com/tv/tv-markets

U.S. Department of Education (2021, August). Title IX and Sex Discrimination. https://www.ed.gov/laws-and-policy/civil-rights-laws/sex-discrimination/Title-IX-and-Sex-Discrimination

VanHaaren, T. (2022, November 9). College football’s new transfer portal windows, explained. ESPN. https://www.espn.com/college-football/story/_/id/34967085/college-football-new-transfer-portal-windows-explained

Walker, T. M. & Russo, R. D. (2024, February 23). Judge rules against NCAA, says NIL compensation rules likely violate antitrust law, harms athletes. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/tennessee-ncaa-lawsuit-nil-7ecfad9c88f8c8baa7e0f4bb00f22ec9

Walker, T. M. (2025, January 31). The NCAA settles lawsuit with Tennessee and Virginia over compensation rules for recruits. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/tennessee-ncaa-lawsuit-nil-eba8f45b9950b9a3ebc699aeeba0f061

Webster, N. R. & Paulsen, R. (2024, July 1). 5 questions after the NCAA’s $2.75 billion settlement to pay college athletes. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/5-questions-after-the-ncaas-2-75b-settlement-to-pay-college-athletes-231665

Young, J. (2021, July 29). To understand why Texas and Oklahoma want to move to the SEC, follow the money. CNBC Sport. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/29/why-texas-and-oklahoma-want-to-move-to-the-sec-follow-the-money.html

About the author

Porter McAndrews

Porter Pellegrin McAndrews is a rising senior at St. Ignatius College Preparatory in San Francisco, CA. Born and raised in San Francisco, Porter plays wide receiver for St. Ignatius’s varsity football team which was California Central Coast Open Division Champions and California Northern Regional Division 1A Runner-Ups in 2024.

Fueled by competing in a wide range of sports with his two older brothers, Mac and Mitchell, Porter has had a love for all aspects of athletics since an early age, a passion that led him to co-found the Sports Analytics Club at his high school and coach and referee youth flag football. Porter is an Eagle Scout, a member of and volunteer for the California Scholastic Federation, a volunteer for the San Francisco/Marin Food Bank, and a St. Ignatius Admissions Ambassador. He intends to study business in college.