Author: Andrew Patel

Mentor: Dr. Ethan Pew

St. Stephen’s Episcopal School

Abstract

Although 73% of workers in the U.S. have access to retirement plans, participation is still substantially lower than ideal at 56% (Bryan et al., 2024). Some barriers are financial, including the rising cost of living, stagnant wages, and the fact that many Americans live paycheck to paycheck. However, many Americans have the means to save but do not. Even among those who participate, savings rates may be insufficient for a secure retirement. As many as 92% of working households do not save enough money relative to their income and age (Rhee, 2013). This paper aims to explore how behavioral economics strategies, such as choice architecture, can be utilized to increase participation in retirement plans among individuals with both access and the capacity to save. Additionally, it examines strategies to increase savings rates among those who currently participate in retirement plans but contribute less than optimally.

Introduction

While millions of Americans have access to employer-sponsored retirement plans, many have still not saved sufficiently for retirement. Psychological barriers to participation, including prioritizing current spending over long-term savings, exist for people who have enough income to save for retirement. Middle-income earners can benefit from programs that utilize techniques that help them overcome psychological barriers in order to increase their savings rate. The benefit of saving money early can make a 20-year-old who saves $400 a month with a 7% average return a millionaire by the age of 65 (The Entrust Group, 2024). Although these middle-income earners often have financial literacy, they lack the incentives to change their financial behaviors. Behavioral economics utilizes strategies that increase participation and, therefore, provide increased financial well-being in retirement.

I. Access and Participation in 401(k) Plans

Although a large portion of employers provide access to retirement plans, there are still a significant number of employees who do not participate due to employment type, income, and company size. The Worker Participation in Employer-Sponsored Pensions: Data in Brief and Recent Trends provides data on pension access and participation rates among U.S. workers. As of March 2023, 73% of all U.S. workers had access to employer-sponsored retirement plans, but only 56% participated (Bryan et al., 2024). Although access is widespread, participation lags significantly. This large gap has implications for retirement savings and preparedness for a large portion of the workforce. Disparities of access and participation rates occur across the workforce based on employment type and job classifications. For example, for civilian workers, only 44% of part-time employees have access to employer-sponsored retirement plans, versus 82% access for full-time workers. Furthermore, income level also affects access. Approximately 90% high-wage earners in the top 25% of wage distribution had access, whereas lower earners in the bottom 25% had 48% access (Bryan et al., 2024). Company size also plays a role in access, with 91% for businesses with over 500 employees versus 53% for companies with fewer than 50 employees. The type of occupation also plays a role in access and participation. Service workers had the lowest rates of access of 43% with only 25% participation, whereas workers in management positions had 86% access with a 74% participation rate (Bryan et al., 2024). These statistics demonstrate that employer-sponsored retirement plans are available to many people, but economic and occupational constraints limit participation. In addition, there is a gap between access and actual enrollment. Strategies need to be implemented to improve access and participation rates, especially among lower-wage and part-time workers, to increase retirement preparedness across all sectors.

II. How Can Access Be Increased

Strategies have increased access to employer-sponsored retirement plans through easier access for part-time workers and tax incentives for employers, but more can still be done. One strategy that has increased access to retirement plans is the SECURE Act 2.0, which offered tax incentives and increased accessibility for employees of small businesses. The SECURE (Setting Every Community Up for Retirement) Act of 2019, followed by the SECURE Act 2.0, incentivized businesses to offer retirement plans to employees by providing tax breaks for those businesses that participated. In 2023, for the first time in history, over 70 million workers had access to 401(k) plans, an increase from 62.3 million in 2021. One major tenet of the SECURE Act that helped to increase access was the section that decreased the number of hours and years part-time workers needed to work to be eligible for employer-sponsored retirement plans (Gappa, 2024). Although the SECURE Act increased access, more still needs to be done. For businesses with fewer than 100 employees, only 34% provided retirement plans. These small businesses cited lack of money (48%), lack of time (22%), and lack of knowledge (21%) as to why they did not offer retirement plans to their employees (Gappa, 2024). These statistics illustrate why small businesses continue to lag behind. Further tax incentives, education, and improving the simplicity of starting an employer-based retirement plan can encourage broader access and participation.

III. Barriers to Participation

Although the SECURE Act 2.0 has increased access to retirement savings, millions of Americans are still unable to contribute to retirement plans due to a mix of economic pressures, including an increase in the cost of living and stagnant wages. According to a MarketWatch survey, 57% of Americans state that they live paycheck to paycheck, which means they have almost no money left after paying for food, rent, and utilities. Furthermore, this financial issue affects younger people more, with 65% of Gen Zers living paycheck to paycheck as opposed to 44% of Baby boomers (Haverstic, 2025). One major barrier to contributing to retirement savings is the cost of living. For example, housing costs for middle-income families in 2018 increased to 34.5% of a family’s total income, up from 27% in 1950 (Bernard & Russell, 2019). Furthermore, the minimum wage in 2025 has remained stagnant since 2009 at $7.25/hour, with little increase from 2002 when the minimum wage was $5.15/hour. Meanwhile, the average cost of a single-family home in 2002 was $224,400 compared to $497,700 in 2025 (Haverstic, 2025). The impact is felt even more in large cities. According to a study by the financial company Smart Assets, an individual living in a large city such as New York City needs to earn a salary of $138,000/year to live comfortably. Living comfortably is defined as a household budget where 50% of income is spent on housing and utilities, 30% on discretionary spending, and 20% savings. This is an hourly wage of $66.62, far more than the average minimum wage (DeJohn, 2024). With the increased cost of living and stagnant wages, many individuals fall short of having disposable income for retirement savings. This is especially true of younger generations between the ages of 19-34 years old, of which 14% fall below the poverty line as opposed to 10.1% of those between the ages of 34-64 (Haverstic, 2025). Many Americans are just trying to survive, not save.

Although many Americans have financial constraints, some surveys demonstrate that some people overreport these financial strains. Approximately 60% of Americans self-report that they live paycheck to paycheck (Srikant, 2025). According to the Federal Reserve, 54% have a three-month emergency savings fund (Federal Reserve, 2024), and 34% live paycheck to paycheck (Bankrate, 2025). This highlights the difference between perception and reality for over 25% of those polled. Strategies can be implemented for those who have the perception of living paycheck to paycheck, but in reality, they do have some income to invest into retirement. Strategies for these people include accurate budgeting, reducing expenses, and increasing income. Being strictly budget-conscious by reducing dining out, buying new clothes, and buying cheaper gas can save a family up to $18,000 per year. Opting for public school over private school can save $42,000 to $84,000 per year for two children (“Embrace Living”, 2025). Other tools for saving money are driving a car for five more years than initially planned, opting out of expensive social activities, and reducing the accumulation of more debt, such as high-interest credit cards (“Embrace Living”, 2025). All of the above strategies can assist those who perceive that they are living paycheck to paycheck to have money to invest in retirement savings.

IV . Why It’s Important to Save and How to Do It

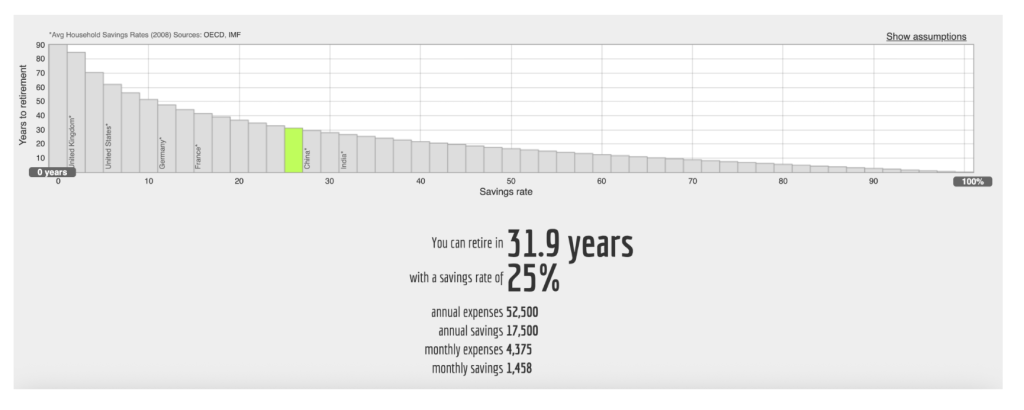

Leveraging compound interest can be a powerful tool to retire early or to support greater financial health in retirement. This requires income to exceed expenses, which may not be uniform across income earning years. In addition, employees should take full advantage of “free money” from employer 401(k) matching. The above strategies, complemented by tax-efficient accounts like HSAs, Roth IRAs, and taxable brokerage accounts, can make financial independence more easily attainable. The time it takes to reach financial independence relies on only one thing-your savings rate, which is the percentage of your salary that you set aside per year. Furthermore, your savings rate is determined by how much money you make and how much you spend in order to have a comfortable life. The most important aspect about a person’s savings rate and the years it will take to retire is that it is an exponential relationship, not linear (“The Shockingly Simple”, 2012). This is the power of compounding. Assuming a 5% investment return after inflation and a 4% withdrawal rate, if a person has a savings rate of 5% they can retire in 66 years, as opposed to a savings rate of 25% a person could retire in 32 years (Networthify, n.d.).

One of the most powerful tools for retiring early is decreasing your spending rate, rather than increasing your income (“The Shockingly Simple”, 2012). If a family chooses to cut a few non-essentials, it could mean that retirement age can be years earlier. Additional strategies for those with disposable income to retire early include building retirement savings, managing taxable income, and utilizing different types of investment accounts. One of the most important steps to pave a path for retirement preparedness is to contribute to a 401(k), especially if it is employer-matched. For example, if an employee with a salary of $80,000 contributes $8000 to their 401(k) and their employer matches $4000 after 30 years at an 8% return, it would be $1.55 million compared to $ 1.06 million if there wasn’t a match (“Early Retirees Guide, 2025). Another important step for those with high deductible health insurance is to utilize a health savings plan to its maximum amount for medical expenses because it is the only account whose contributions are tax-deductible with tax-free growth and withdrawals, a triple tax benefit (“Early Retirees Guide, 2025). For those with a lower income (less than 24% income bracket), a Roth IRA is another account that is important to fund because it can help maximize income that is tax-free in retirement. Another important way to prepare for retirement is to fund a taxable brokerage account. Although it lacks tax advantages, a taxable brokerage account has tremendous flexibility with no income limits, contribution limits, or penalties for withdrawal, therefore making it a good source of dividend income and money that is easily accessible for retirees (“Early Retirees Guide, 2025). The above step-by-step guide utilizes compounding interest, taking advantage of 401(k) employer-matching, along with other tax advantage accounts to help Americans save more.

V . Behavioral Economics and Nudging Better Decisions

Many people struggle to save for retirement, not because they lack the desire, but because of psychological biases that lead them to prioritize current spending over long-term savings goals. Behavioral economics examines when, how, and why decisions, on occasion, systematically vary from purely economically rational choices (Samson, 2014). In some cases, behavior is influenced by the structure and presentation of choices; this is known as choice architecture (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). One powerful example of choice architecture is the default choice, which is a predetermined option that is automatically set if an alternative is not actively selected. Most often, people select the default choice (Samson, 2014). In other cases, decisions depend on heuristics, shortcuts to speed up or reduce the informational burden involved in decision making (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). An example of heuristics is anchoring, where there is initial exposure to a number that establishes a reference point which the user then makes a judgment, and then this gives perceived value of a product (Samson, 2014). For example, if a fully loaded computer is $2000 but the customer makes customizations that make the price $1500, it is then viewed as a bargain even though the base model is $1000 (Samson, 2014). And yet in other cases, decisions may reflect biases related to cognitive or emotional factors. An example of this is the prospect theory, where people do not make the most rational choices when an option is framed as a win or a loss. Since people hate to lose, they often select a less optimal choice as long as they perceive that they will not lose anything (Samson, 2014). Understanding these influences allows individuals to consider where they may be leaving money on the table. Also, allowing for those setting policies, such as in a corporate setting for employees or in a government setting for citizens, to introduce nudges (part of choice architecture that alters a person’s behavior without giving up individual choice) that leverage the systematic nature of behavioral economics in influencing decisions (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). Thoughtfully designing choices using nudges can produce better results while still preserving individual freedom to make alternative selections.

VI. Utilizing Behavioral Economics to Increase 401(k) Participation

Behavioral economics is an important part of financial well-being because financial literacy only improves knowledge, but does not change financial behaviors. Behavioral economics is growing because research has proven that financial literacy does not equate to financial well-being, the financial landscape has become significantly more complex, and individuals are now tasked with the massive responsibility of managing their retirement well-being (Soman & Choe, 2023). The power of behavioral economics can be utilized to create strategies to aid in an increase in participation in retirement funding, particularly by leveraging inertia with default options and automatic enrollment. Inertia, where people tend to stay with their current situation even after receiving new information, can be used as a powerful tool in behavioral economics (Hreha, 2023). Researchers compiled data from a large corporation in the United States that changed its 401(k) participation options from opt-in to automatic enrollment as a default. With automatic enrollment, participation rose significantly to 86%, as opposed to 49% where employees needed to make an effort to opt in, thus demonstrating the power of inertia (Madrian & Shea, 2001). Another tool in behavioral economics is choice architecture, where the way or amount of choices presented can affect participation. A study of over 800,000 employees at one company demonstrated that 401(k) participation dropped by 1.5-2% for every ten funds added; furthermore, participation rates were at their highest at 75% when only two funds were offered (Iyengar et al., 2003). Choice architecture was an effective nudge in increasing 401(k) participation. One of the most well-known behavioral interventions is a program called Save More Tomorrow (SMarT). In this program, participants commit to saving now from future pay raises, and once the employee is enrolled, they need to opt out to leave the program. This program takes advantage of using the present time to decide the future, therefore taking advantage of present bias, where the participant does not feel like they lose or sacrifice anything in the present time (Benartzi, 2017). Also, the participant never has a base pay that decreases because their take-home salary does not decrease, therefore taking advantage of the fact that the employee does not feel a loss of money and avoids the feeling of loss aversion. Third, the program takes advantage of inertia, because the participant has to actively opt out if they no longer want to participate. The SMarT program has helped 15 million Americans save for retirement. Because it was so successful, it became a part of the Pension Protection Act of 2006 (Benartzi, 2017). This program demonstrated the successful utilization of behavioral economics to increase savings for retirement readiness.

Conclusion

Although many Americans have access to employer-sponsored retirement plans, there remains a large gap in participation due to economic and psychological barriers. However, access alone is not enough. Behavior plays an important role in financial planning. Behavioral economics can not only provide insight as to why people do not save for retirement, but the field can also help increase participation rates. Behavioral strategies that utilize choice architecture and inertia have proven valuable in raising participation rates through automatic enrollment and simplifying plan options. Ultimately, financial well-being in retirement can be significantly impacted by designing plans utilizing behavioral economics that align with human behavior.

Acknowledgements

Andrew Patel would like to thank Dr. Ethan Pew, Clinical Assistant Professor of Marketing at The University of Texas at Austin McCombs School of Business, for mentoring him throughout the process of writing this paper.

References

Benartzi, S. (2017). Save More Tomorrow. Save More Tomorrow. Retrieved August 3, 2025, from http://www.shlomobenartzi.com/save-more-tomorrow

Bernard, T. S., & Russell, K. (2019, October 3). The Middle-Class Crunch: A Look at 4 Family Budgets. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/10/03/your-money/middle-class-income.html

Bryan, Sylvia, L., Myers, Elizabeth, A., Topeleski, & John, J. (2024, September 18). Worker Participation in Employer-Sponsored Pensions: Data in Brief and Recent Trends. Congress. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R43439

DeJohn, J. (2024, March 19). Salary Needed to Live Comfortably ? 2024 Study (A. Conde, Ed.). SmartAsset.Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://smartasset.com/data-studies/salary-needed-live-comfortably-2024

The Early Retiree’s Guide to Funding Retirement Accounts. (2025, May 2). FinancialSamurai. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://www.financialsamurai.com/the-early-retirees-guide-to-funding-retirement-accounts/

Embrace Living Paycheck-To-Paycheck To One Day Be Free. (2025, May 28). FinancialSamurai. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://www.financialsamurai.com/embrace-living-paycheck-to-paycheck-then-get-out

Gappa, S. (2024, June 18). 401(k) Account Access Statistics in 2023 (R. Hartill, Ed.). Capitalize. Retrieved August 1, 2025, from https://www.hicapitalize.com/resources/401k-account-access-statistics

Haverstic, C. (2025, May 14). 57% of Americans Live Paycheck to Paycheck in 2025 (C. Hill, Ed.). MarketWatch. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://www.marketwatch.com/financial-guides/banking/paycheck-to-paycheck-statistics

Hreha, J. (2023). What is Inertia In Behavioral Economics? The Behavioral Scientist. Retrieved August 3, 2025, from https://www.thebehavioralscientist.com/glossary/inertia

Madrian, B., & Shea, D. (2001). THE POWER OF SUGGESTION: INERTIA IN 401(k) PARTICIPATION AND SAVINGS BEHAVIOR. Quarterly Journal of Economics, CXVI(4), 1149-1187.

Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2023. (2024, May). Federal Reserve. Retrieved August 3, 2025, from https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/2024-economic-well-being-of-us-household s-in-2023-expenses.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Retirement Planning Tips for Every Age: 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s. (2024, October 21). The Entrust Group. Retrieved August 10, 2025, from https://www.theentrustgroup.com/blog/retirement-planning-tips-every-age

Samson, A. (n.d.). An Introduction to Behavioral Economics. Behavioral Economics. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/introduction-behavioral-economics/

Sethi-Iyengar, S., Huberman, G., & Jiang, W. (2003, January 1). How Much Choice is Too Much?: Contributions to 401(k) Retirement Plans.

The Shockingly Simple Math Behind Early Retirement. (2012, January 13). Mr. Money Mustache. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://www.mrmoneymustache.com/2012/01/13/the-shockingly-simple-math-behind-early-retirement/

Soman, D., & Choe, Y . (2023). Research handbook on nudges and society (L. A. Reisch & C. R. Sunstein, Eds.). Edward Elgar. Chapter 8: Behavioural interventions to improve financial wellbeing: a focus on budgeting

Srikant, K. (2025, February 26). Fact Check: Is there a consensus that a majority of Americans are living paycheck to paycheck? Econofact. Retrieved August 2, 2025, from https://econofact.org/factbrief/is-there-a-consensus-that-a-majority-of-americans-are-livin g-paycheck-to-paycheck

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge : improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness (Revised and expanded edition ed.). Penguin Books.

When can I retire? (n.d.). Networthify. Retrieved August 3, 2025, fromhttps://networthify.com/calculator/earlyretirement?income=70000&initialBalance=0&expenses=52500&annualPct=5&withdrawalRate=4

Rhee, N. (2013, June). The Retirement Savings Crisis: Is It Worse Than We Think? National Institute on Retirement Security. Retrieved August 14, 2025, from https://www.nirsonline.org/reports/the-retirement-savings-crisis-is-it-worse-than-we-think/

About the author

Andrew Patel

Andrew is a sophomore at St. Stephen’s Episcopal School in Austin, Texas. He enjoys exploring topics in business, finance, and investment strategies. He has participated in leadership roles in his school’s business and investment clubs. He hopes to promote financial literacy to help others make informed decisions about money management and achieve financial goals.