Author: Aidan Ko

Mentor: Dr. Eric Golson

High School of Liberal Arts Success Academy Manhattan

Introduction

The global aviation industry is dominated by two companies—US based Boeing and European based Airbus—together accounting for over 93% of the single-aisle aircraft segment. This duopoly has set the standards for innovation, safety, and service infrastructure. China’s Commercial Aircraft Corporation (COMAC) is a newcomer to this segment of aviation with the C919 which is to compete against the Airbus A320 and Boeing 737 Max series of jets. The C919 made its debut with China Eastern Airlines in 2023 marking a new step in China’s goal of technological self-reliance. This paper explores whether the C919 can be a serious competitor in the large airliner market.

COMAC’s order backlog of C919s is estimated to be between 713-1,000 aircraft, largely from Chinese carriers: Air China, China Eastern, and China Southern. In 2024 alone, the C919 recorded approximately 300 new orders, representing nearly a quarter of global single-aisle orders that year. For a newcomer that’s very impressive. However, most of the orders are Chinese and it is unclear whether they can deliver on their current order book. While it is strong in the domestic market it has challenges it must overcome the current duopoly. An example being regulatory hurdles like the European Aviation Safety Agency anticipating a 3–6 year process before C919 can fly in EU airspace.

The Chinese government’s other goal is to make this aircraft entirely in China with Chinese components. In order to achieve this goal of self-reliance Chinese manufacturers are making Chinese made engines and other components for the C919. China wishes to be self-reliant in the manufacturing of this new aircraft but still relies on Western made parts critical to its operation, including General Electric engines and Honeywell made flight controls.

At the same time Boeing and Airbus are constrained by production capabilities, issues, and full order books. Airbus is reportedly sold out its A320neo slots for the rest of the decade and Boeing is swamped with quality and delivery setbacks. This could create openings for COMAC, especially if they can offer competitive pricing, and attract international buyers.

This paper will test whether the COMAC C919 can expand past its domestic foothold to compete in the global market. It will analyze the aircraft’s capabilities, market position, regulatory barriers, geopolitical hurdles, and lastly short-term and long-term disruptive potential.

Overview of the C919 and its Development Cost

The C919 project began in January 2009 a year after China established COMAC to compete against the dominance of Boeing and Airbus. The program targeted a maiden flight by 2014 but the first prototype flew on May 5, 2017, followed by several flight-test aircraft verifying systems through 2019. By September 2022 COMAC received CAAC (Civil Aviation Administration of China) certification and delivered the first production C919 to China Eastern Airlines on December 9, 2022. COMAC has ramped up production in its pre mass production phase with plans aiming for 30 deliveries in 2025. It will then proceed to increase capacity to 50 aircraft per year. COMAC’s long-term ambition is to reach 150 C919 deliveries annually within five years as it would rival Boeing and Airbus narrow-body output.

Technical Specifications

The C919 is a conventional twin-engine narrow-body airliner seating 156–174 passengers, depending on configurations of the aircraft, with a range of 2200 nautical miles at maximum payload shown on COMAC’s website. The C919 uses Western made equipment like the CFM International LEAP‑1C engines, from GE (US) and Safran (France), and avionics supplied through joint ventures with firms like Honeywell. COMAC is developing a domestic engine called the CJ-1000A, with first engine test runs in 2017 and flight testing expected soon . These new engines will reduce dependency on Western engines and other equipment. This can also change the specifications of the aircraft in the future.

Development Costs

Official figures for the C919’s program are not regularly available as Comac does not publish program costs or a list price for the C919. A 2017 report by NBC News said the C919 jet was developed at a cost of $8.6 billion. An estimate by PilotPassion priced the individual aircraft cost at between $90-100 million. It has also been reported that a state-subsidized deal saw COMAC charging $108 million per jet to Air China, raising the original selling price from the $50–60 million per plane initially proposed as market competitive by COMAC; at this price the C919 is more expensive than a newly manufactured 737 Max 7 aircraft which has a 2025 list price of $99.7 million [AXON, 2025].

A fair comparison to the development of the C919 is the C-series development costs which highlights the financial burden and strategic risks involved in entering the commercial aircraft market. COMAC allocated around $8.6 billion USD for the C919’s development, though the true cost, when you include delays, may approach $15–20 billion [Walsh, 2023]. Backed by the Chinese government as a national industrial priority, the C919 was developed over 15 years. In contrast, the Bombardier C-Series program, initially budgeted at $2.1 billion, saw its costs balloon to over $5.4 billion due to delays and low early sales [Trimble, 2013][Lu, 2015]. Unlike COMAC, Bombardier did not have state backing and ceded control of the program to Airbus in 2018 to avoid bankruptcy. The COMAC case shows that while they had state backing the development costs are way out of proportion compared to Bombardier, and later Airbus, so the breakeven point for this program is likely to be much higher.

The C919 as an Import Substitution Strategy?

An import substitution is when a country will make a political choice to make things which substitute for international market goods when they want to promote domestic production or cut reliance on foreign powers. This has historically been proven to be devastating to some economies like in LatinAmerica where goods being produced in their native countries would be sold at a loss, subsidized by governments, to promote domestic economic growth.

China may be doing this within the framework of the “Made in China 2025” industrial policy. This initiative aims to reduce reliance on foreign technologies in critical sectors by cultivating domestic innovation and production capabilities. In the case of the C919, while the initial versions of the aircraft heavily depend on Western components such as CFM International LEAP-1C engines, Honeywell avionics, and Rockwell Collins communication systems, China has made it clear their intention to gradually replace these with indigenous alternatives. This is shown with the development of the CJ-1000A engine by the Aero Engine Corporation of China (AECC), designed to eventually replace the LEAP-1C and make the C919 fully domestically powered.

This push reflects a strategy which ensures technological independence from geopolitical risks, like U.S. export controls, which recently have been turbulent. At the moment China is selling their C919 at a loss to promote the aircraft as a success. Import substitution is being used to push these efforts to produce a competitive aircraft and build a self-sufficient aviation industry capable of challenging Western dominance at every level of the supply chain. The political choice and unanswered question is for how long China will be willing to subsidize this domestic aircraft.

The Boeing-Airbus Duopoly

Boeing

Founded in 1916 in Seattle, Washington, Boeing is one of the oldest and one of the most influential aerospace companies in the world. Its commercial aircraft division gained global prominence with the launch of the 707 jetliner in the 1950s and became the standard of civil aviation with models like the 737, 747, 777, and 787 Dreamliner. The 737 series, in particular, became the best-selling commercial aircraft family in history, cementing its dominance in the narrow-body market.

Boeing’s competitive edge has historically included its global support infrastructure, long-standing relationships with airlines, and U.S. government influence in international trade negotiations. However, recent setbacks, like the 737 MAX grounding in 2019 after two fatal crashes and ongoing quality control issues, have damaged its reputation and disrupted its delivery schedules. It has provided an opening for them to lose customers to the other large aircraft company, Airbus, and potential new entrants like COMAC.

Airbus

Airbus was founded in 1970 as a European consortium to compete with U.S. manufacturers like Boeing. Headquartered in Toulouse, France, Airbus rose to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s with successful aircraft like the A320, which introduced fly-by-wire technology, becoming a standard in many aircraft today. Airbus solidified its presence in the wide-body market with the A330 and later challenged Boeing’s long-haul dominance with the A350 and superjumbo A380.

Airbus has matched or exceeded Boeing in annual deliveries for several years, particularly in the wake of the 737 MAX crisis. Its A320neo family, launched in 2016, quickly became the standard in fuel-efficient, single-aisle aircraft, and has outsold the 737 MAX in recent years. With strong support from the European Union it is now considered to be an equal to Boeing creating the Boeing-Airbus duopoly in the commercial airliner market.

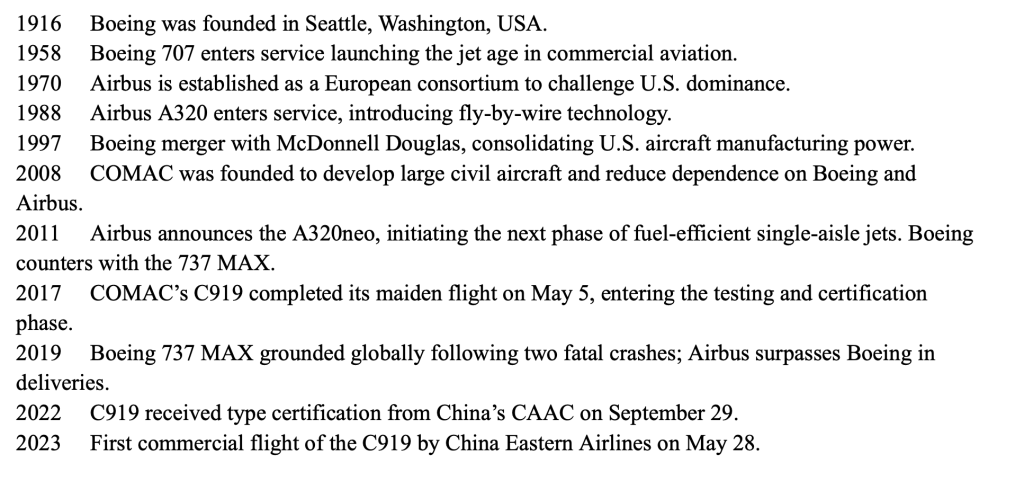

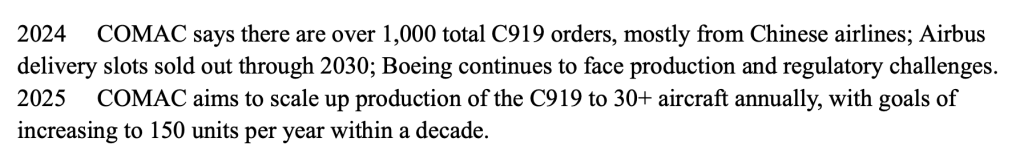

Timeline

This monopoly could be broken in time with indigenous projects like China’s CJ-1000A engine and domestic avionics development, which could mature into more competitive alternatives over time. If successful this might pressure Western firms to invest more heavily in innovation to stay ahead of a rising competitor. COMAC may create price competition by offering aircraft at lower or subsidized prices. Especially in emerging markets or within the Global South if COMAC gains momentum. It would force Boeing and Airbus to innovate in how aircraft are marketed and supported.

Airbus may face more immediate competitive pressure due to its deeper integration with the Chinese aviation market. Since 2008, Airbus has operated a final assembly line for A320 aircraft in Tianjin, China. This facility reflects Airbus’s pivot toward the Chinese market while placing it in the proximity of COMAC’s industrial and political sphere. The C919’s flight control systems and overall cockpit are more closely modeled on Airbus’s designs which make the aircraft more familiar for Airbus-trained pilots and maintenance crews. Chinese airlines familiar with Airbus systems may see the C919 as an easy transition, especially for domestic use. This could severely threaten Airbus’ position within China and more widely in Asia. But any change to global innovation between the three players will only happen in the long-term if COMAC is able to certify internationally, improve supply-chain independence, and scale production competitively.

Market Analysis

Previous new entrants and challenges to the Boeing-Airbus duopoly have not fared particularly well. The A220’s development began with Bombardier as the C‑Series, with initial budget projections at around US $2.1 billion, equally funded by Bombardier and the Canadian government. Over time program delays, rising complexity, and increased testing costs raised total expenditure to around US $3.5 billion.Accounting write‑downs and financial restructuring later brought the all‑in development cost to roughly US $5.4 billion. An important part in this story is also the engine costs. The PW1500G geared‑turbofan engine was developed specifically for the A220 at an estimated 10 billion dollars. The engine itself will retail at US $12 million per engine depending on maintenance commitments and airline negotiations (Hartley, 2025). Early manufacturing costs for the A220 were estimated at about US $33 million per airframe, including general and administrative overhead and supply chain inefficiencies.[Memon, 2023]. Bombardier originally sold some aircraft at below cost. Some examples were at the low price of $24 million in aggressive pricing strategies. This prompted a U.S. trade petition alleging the practice of dumping. [ Ogechi, 2025]

The A220 program shows how an aircraft can succeed but still struggle commercially due to high development costs and component issues. Pricing individual units below cost early on, Bombardier couldn’t absorb losses long-term without a strategic partnership. This eventually led to Airbus’s involvement and then to majority ownership of the Bombardier C-Series, later renamed the A220 programme.

The C919, backed by long-term state investment, reflects an even larger financial commitment, but benefits from sheer scale expectation in China’s domestic aviation market. While its unit price exceeds Western competitors, COMAC subsidizes production heavily to cover initial losses which is similar to the C-Series’s early years, but on a larger scale. The question is how long is COMAC and the Chinese government willing to subsidize the production and sale of the C919.

C919 costs

COMAC officially stated a development budget of around US $8.6 billion, but independent assessments suggest real costs likely exceed US $20 billion. Unit cost estimates for the C919 are not certain as COMAC does not announce actual figures but estimates are around $90-$100 million per airframe as previously suggested. Higher from earlier estimates of about $50–60 million per airframe. This is higher than the Boeing 737 Max and A320 family of aircraft. Now while that might be discouraging to the aircraft’s success the state government has been seen subsidizing the sale of the aircraft to domestic carriers at lower prices per airframe. This represents a failure to compete on price unless subsidized by the government. To which customers and for how long the Chinese government might be willing to provide such subsidies remains unclear.

Strategic and Geopolitical Dimensions

Boeing’s Political Vulnerability and Export Disruptions

Political entanglements, particularly in the Second Trump administration, introduces long-lasting vulnerabilities to Boeing. In 2025 trade tensions led to Chinese authorities banning domestic airlines from accepting new Boeing aircraft and American aircraft parts as retaliation from measures of US imposed tariffs as high as 145% on Chinese goods. China returned several Boeing 737 MAX jets to U.S. facilities which strand millions of dollars worth of inventory. Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg confirmed that many airline clients had stopped taking delivery of ordered aircraft. This exposes Boeing’s operations and its vulnerabilities to do business internationally, specifically in China, weakening the duopoly between Airbus and Boeing by adding political tensions. It allows COMAC to also add itself to the competition as Boeing is in a weakened state.

American and European governments might not play fair as the exposure felt by a new competitor might push them to impose tariffs on COMAC’s planes, making them uneconomical. This happened to Airbus and Bombardier with the A220 when this line was subjected to American tariffs; this was due in part to Boeing feeing the need to cut out another potential competitor to their 737 MAX jets. The fact that it is also a Chinese made product also puts into question if the U.S. or EU will approve the use of it in their airspace. So China will need to overcome these hurdles in order to improve their odds at being feasible on the international market.

China’s Export Strategy

China’s use of aircraft exports as a tool of diplomacy and influence is consistent with its broader economic strategy. Under the Belt and Road Initiative, China has funded infrastructure projects across Pakistan, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America. These are done through outright subsidies of the Chinese government or loans. COMAC can use this to their advantage and leverage these relationships. COMAC has done promotional campaigns in early 2024, with promotional flights designed to establish market trust and set attractive terms to the table.

The development of the C919 is deeply interwoven with China’s industrial strategy of advanced technology and products being made in China using state subsidies, infrastructure investments, and direct financial support to maintain production momentum. Analysts at CSIS say COMAC had received between $49 billion and $72 billion USD in Chinese government support. [8] These injections allow COMAC to price the C919 competitively, and give benefits to those who buy the jet, to build market share. In target regions Chinese firms will often sell products at a loss to maintain employment, future influence, and deepen trade ties. These tactics are shown across Chinese businesses. Selling aircraft cheaply in developing markets enables COMAC to establish an operational footprint for Chinese made products and foster brand familiarity before profitability becomes a possibility.

What now?

This introduces new competition dynamics for Boeing and Airbus, Boeing struggles with export bans and political backlash while Airbus, with an A320 final assembly line in Tianjin, has deeper ties within the Chinese system. China’s ability to redirect domestic airlines from Boeing or Airbus to COMAC reflects strategic maneuvering to weaken American dominance. If COMAC scales effectively it doesn’t just compete technologically but will reshape and reorient the framework of commercial aviation.

The emergence of the C919 reflects a convergence of economic policy and geopolitics: state-subsidized aviation supporting a broader Chinese strategy. Through loss-leading exports, import substitution, infrastructure partnerships, and strategic targeting of developing markets, the C919 could serve as a lever. This stands in contrast to Boeing’s more conventional, market-driven model which can make the duopoly unstable and potentially prompting both Airbus and Boeing to rethink their global positioning.

Long-Term Outlook and Challenges

One of COMAC’s most significant hurdles is overcoming skepticism toward Chinese made commercial aircraft, especially in markets where aviation safety is closely tied to brand trust. While the domestic market may become accustomed to flying on the C919 due to the strong presence of state-owned airlines, international passengers, mostly in North America and Europe, may be more hesitant. For airlines, the decision to buy a C919 depends on cost competitiveness, operational reliability, parts availability, and fuel efficiency compared to Boeing and Airbus offerings. However, for passengers the primary drivers are safety and comfort. It is not clear how they might feel about a new entrant. COMAC also needs to establish a maintenance and parts network to support the aircrafts they wish to sell and also create a good safety record. This can be done through transparent operations and regulatory oversight by reliable aviation organizations. Public perception can also be influenced by geopolitics and media perception between China and certain countries could amplify hesitancy to fly on a Chinese-made jet, regardless of the aircraft’s approval and safety.

The C919 holds certification only from the CAAC in China. Without approvals from the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) or the U.S. FAA the C919 cannot operate with most major Western airlines or fly in certain markets. The EASA certification process is estimated to take three to six years, with no delays or needing to change the aircraft characteristics. The FAA might take longer. This can delay the C919’s short term market potential outside China. Securing certifications will require compliance with international safety standards and the testing of Chinese systems internationally.

China has been heavily subsidizing domestic sales to sell aircrafts to Chinese airlines, offering favorable financing terms and reduced prices. Once the C919 secures foreign certification and builds a safety record, China could strategically deploy subsidies internationally like developing markets where cost competitiveness can override brand concerns. This would align with China’s export strategy in which pricing is used as a tool of geopolitical influence.

If COMAC can overcome certification hurdles and prove operational reliability the C919 could slowly chip away at Boeing and Airbus’s dominance in select markets. However, reputational trust will likely be the decisive factor. The first decade of service will be critical as strong performance, absence of major incidents, competitive pricing, and effective global maintenance support could take the C919 from a domestically favored jet into a competitive product internationally.

Conclusion

The COMAC C919 represents China’s most ambitious attempt to achieve domestic self-reliance and challenge the duopoly held by Boeing and Airbus in the global commercial aviation market. Backed by state investment, industrial policy, and a growing domestic aviation market, the C919 is a geopolitical instrument and a symbol of China’s push toward technological self-reliance. While its technicals and some design aspects mirror some of Airbus’s aircraft, its long-term goals and potential lies in its ability to scale production, reduce dependence on foreign components, and secure sales internationally. However, significant challenges remain. From certification delays and limited global trust to the hurdles of building a global support system and winning over airline customers and passengers COMAC has an uphill battle to fight. The public and airlines continue to favor the established aircraft manufactures and the lack of FAA or EASA certification restricts the C919’s international reach. Also political instability, especially involving America and Chinese relations, have already disrupted many of the traditional aspects of the duopoly. This offers COMAC a rare opening to expand into cost sensitive markets in Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

It is also worth noting Airbus was born in a similar story to COMAC in the 1970s and 1980s, when it was founded as a new player in the civil aviation market. Before Airbus, American giants like Boeing dominated the world of civil aviation. It seemed unlikely that Airbus could unseat Boeing and America’s monopoly on the industry but through sustained government support, multinational European cooperation, and a focus on technological innovation, like the introduction of fly-by-wire controls in the A320, Airbus gained market share, slowly but it reshaped the landscape of civil aviation. COMAC appears to be following a similar playbook with investment in domestic manufacturing, support from the government, and achieving strategic trade goals rather than initial profitability. It could replicate Airbus’s path which can transform it from a purely domestic competitor into a global competitor.

The C919’s commercial viability will depend on how effectively COMAC can navigate the next decade and the international markets, building partnerships, and establishing long-term operational reliability. While it is unlikely to unseat Boeing or Airbus in the near term, the C919 could reshape the landscape, even promote innovation, especially if China begins to use aircraft exports as a tool for economic diplomacy. The C919 is not disrupting the Airbus and Boeing duopoly at the moment but its recent progress and potential progress signals that the era of an unchallenged duopoly may be approaching its end.

Bibliography

AXON Aviation Group. “Aircraft Pricing. ” AXON Aviation, 2024, www.axonaviation.com/commercial-aircraft/aircraft-data/aircraft-pricing.

Baculinao, Eric. “China’s C919 Passenger Jet Makes Maiden Flight in Challenge to Boeing, Airbus.” NBC News, 4 May 2017, www.nbcnews.com/news/china/china-s-c919-passenger-jet-set-maiden-flight-challenge-boeing-n754171.

Bjorn Fehrm. “How Much Did the CSeries Cost Bombardier? – Leeham News and Analysis.” Leeham News and Analysis, 20 Feb. 2020, leehamnews.com/2020/02/20/what-did-the-cseries-cost-bombardier/.

Grant, Eli. “The Long Road to Certification: China’s C919 Faces European Delays, Raising Stakes for Global Ambitions.” Ainvest, 29 Apr. 2025,www.ainvest.com/news/long-road-certification-china-c919-faces-european-delays-raising-stakes-global-ambitions-2504/.

Hartley, Paul. “How Much New Commercial Jet Engines Cost.” Simple Flying, 9 Apr. 2025,simpleflying.com/how-much-new-commercial-jet-engines-cost/.

Lee, Amanda.“South China Morning Post.” South China Morning Post, 29 May 2023,www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3222192/chinas-c919-timeline-2008-23-first-commercial-flight-15-years-making.

Lu, Vanessa.“The Toronto Star.” Toronto Star, 18 Dec. 2015, www.thestar.com/business/bombardier-s-cseries-jet-certified-for-commercial-service/article_8b-58d9-bb8c-b0e9adddbb5f.html.dad0d7a3-11

Memon, Omar.“How the Bombardier C-Series Program Transitioned to the Airbus A220 Family.”Simple Flying, 14 Mar. 2023, simpleflying.com/bombardier-c-series-airbus-a220-transition-story/.

Ogechi.L. “The Story of Airbus A220. An Aircraft Boeing Didn’t Like.” Medium, 18 June 2025,medium.com/%40OgechiL/the-story-of-airbus-a220-an-aircraft-boeing-didnt-like-3f607d4978d9.

Ostrower, Jon.“Airbus Quietly Cultivates ‘Building Block’ Tech for A320 Successor.” The Air Current, 9Dec. 2022, theaircurrent.com/technology/airbus-eaction-xwing-a320-successor/.

Ostrower, Jon.“U.S. Engine and Component Ban Poised to Cripple China’s Commercial Aircraft Manufacturing.” The Air Current, 7 June 2025,theaircurrent.com/china/us-china-jetliner-restrictions-ge-rtx-honeywell-comac/.

Shah, Aditi, and Tim Hepher.“Aircraft Lessor DAE Sees China’s COMAC Breaking Airbus, Boeing Duopoly.” Reuters, 21 June 2024,www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/aircraft-lessor-dae-sees-chinas-comac-breaking-airbus-boeing-duopoly-2024-06-21/.

“South China Morning Post.” South China Morning Post, 25 Dec. 2023,www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3246205/chinas-c919-jet-scores-higher-price-latest-deal-boeing-returns-market.

Spray, Aaron.“Airbus vs Boeing vs COMAC: How the Plane Makers’ Market Share Compares in Asia.”Simple Flying, 3 Feb. 2025, simpleflying.com/airbus-boeing-comac-market-share-asia/.

Spray, Aaron.“How Much Does a Boeing 737 MAX Cost in 2025?” Simple Flying, 8 Apr. 2025,simpleflying.com/boeing-737-max-cost-2025/.

Terlep, Sharon.“Boeing Hit from All Sides in Trump’s Trade War.” WSJ, The Wall Street Journal, 15 Apr. 2025, www.wsj.com/business/airlines/boeing-hit-from-all-sides-in-trumps-trade-war-cdc616d6.

Toure, Seydou. “Comac Breaks through against Airbus and Boeing.” Sneci, 10 Mar. 2025,www.sneci.com/en/comac-breaks-through-against-airbus-and-boeing.

Trimble, Stephen.“Bombardier Acknowledges CSeries Cost Pressure.” Flight Global, 16 Sept. 2013,Bombardier acknowledges CSeries cost pressure | News | Flight Global

Walsh, Sean. “How Much Does a Comac C919 Cost? (2024 Price).” Pilot Passion, 30 May 2023,pilotpassion.com/comac-c919-cost/.

About the author

Aidan Ko

Aidan is a Senior at Success Academy High School in Manhattan. He has always been interested in economics and its impact on the world around us and political conversations. Aidan participates in Model UN, as it perfectly incorporates his interests, and he follows the stock market during the day to track trends.