Author: Kyle Padilla

Mentor: Dr. Nikolas Webster

Pennsylvania Leadership Charter School

Abstract

Every four years, swimming and track draw some of the largest audiences during the Olympic Games, yet both sports struggle to maintain consistent fandom outside the Olympics. This study explores the historical development, viewership patterns, and fan engagement strategies for these sports using news articles, Olympic broadcasts, social media analytics, and prior research on sport fandom. The Psychological Continuum Model helps explain why many Olympic viewers only reach the initial stages of interest and attraction, without developing a deeper attachment or loyalty to the sport. Swimming and track face challenges in turning this short-term excitement into lasting fan engagement. Improvements in venues, technology, and storytelling could help. For example, hosting meets in spectator-friendly facilities, using broadcast innovations to highlight athletes’ performances, sharing athlete storylines, and promoting rivalries may encourage fans to stay interested beyond the Olympics. Understanding these patterns is important for athletes, coaches, and sports organizations looking to build stronger and consistent support for nonrevenue sports. This study finds that national pride, media exposure, and athlete success drive short-term engagement, but sustainable fandom requires consistent access to competitions, compelling narratives, and emotional connections between fans and athletes. These findings provide insight for teams, sport marketers, and program directors aiming to grow and maintain interest in swimming and track beyond the Olympic spotlight.

Introduction

Every four years, the world’s best athletes face off against each other in the Olympic Games. Competing for the Olympic medals and national pride, they put on a great show for spectators across the world. This historic competition has united countries and created iconic moments in sports history (Canadian Equality Consulting, 2024). The Olympics have an impressive reach: in 2024 around 5 billion people followed the Olympics (International Olympic Committee, 2024). That’s about 84% of the global potential audience. During the Olympics, certain sports are more viewed than others. Both swimming and track and field are among the most watched sports during the Olympics. Despite being fan-favorites during the Olympics, both these sports fail to maintain the fandom that other Olympic sports like basketball or soccer sustain year round (Campbell, 2024). Looking at the history and development of both these sports and the Olympics provides important insight into why swimming and track attract massive Olympic audiences but fail to sustain fandom year-round. Additionally, the Psychological Continuum Model (PCM) helps explain this pattern, as many Olympic viewers may only reach the initial attraction stage (Funk & James, 2001) during the Games but fail to progress toward lasting attachment or allegiance once the spectacle ends.

Understanding this unique fandom pattern is important for sports organizations looking to grow, athletes who rely on fan support, and sports programs looking to be self-sustainable. Both swimming and track are considered nonrevenue sports, meaning they don’t generate consistent income from ticket sales, broadcasting rights, or merchandise. Instead, these sports programs are often supported by the financial success of major sports programs like football and basketball (James & Ross, 2004). If coaches, athletes, and entire sports programs can better understand sport fandom and motivation, nonrevenue sports can turn into self-supporting, revenue generating sports.

Both swimming and track and field fandom have several barriers and constraints that prevent long term fans. These issues can be broken down into two broad categories: the built experience (venue, structure, and tech) and the narrative and emotional connection (storylines, identity). The Olympics naturally provides “fixes” for some of these issues. Boasting impressive stadiums and groundbreaking technology, in-person fans at the Olympics and viewers from home get an enhanced experience. Additionally, fans are drawn into the Games and the storylines created through national pride and rivalries – two things that these sports normally lack. Finally, one innate problem with both sports is the athletes’ hesitancy to race frequently. Top athletes only race a handful of times per year, usually these meets include national champs, World Champs, and NCAAs for the collegiate athletes. This leaves fans with very few opportunities to watch exciting races between the best athletes. The Olympic Games are seen as the world’s most premier athletic competition, so naturally all top athletes choose to compete for their spot on the Olympic team. This paper argues that while swimming and track are among the most-watched Olympic sports, they struggle to maintain fandom outside the Games because they lack the consistent venues, rivalries, and storylines needed to build long-term fan communities.

History of Competitive Swimming

Swimming became a modern competitive sport in the mid 19th century (The History of Olympic Swimming, 2018). Before that moment, swimming was present across the globe, but primarily for recreation and survival. Today, swimming is a worldwide sport and an Olympic classic. Swimming was a part of some civilizations as early as 2500 BC in Egypt (Athanasiou, 2024). In the 16th and 17th centuries, swimming became a form of training and a sign of prestige for ordinary people in society (Vasile et al., 2023). Particularly during the Renaissance and Enlightenment, since swimming was promoted as part of a well-rounded, classical education. By the 20th century, swimming’s benefits to human health and wellbeing were becoming clear, and people saw swimming as an excellent and accessible way to stay in shape, regardless of age, mobility, and social position (Vasile etal., 2023). Swimming’s popularity dramatically increased in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, when Olympic icons like Dawn Fraser, Mark Spitz, Michael Phelps, and Katie Ledecky showcased their talent and dominance on the global stage. Competitive swimming saw an increase in popularity and many competitive swim clubs began forming around the world (Lohn, 2025).

In recent years, swimming experienced significant growth in popularity. In 2022, US Swimming Nationals had 572,000 viewers on NBC, according to Nielsen ratings (Keith, 2022). This was an increase from that same summer’s Swimming World Championships, which only received about 200,000 viewers (Keith, 2022). Even more impressive, World Aquatics’ social media platforms had 1.3 billion impressions, 621 million engagements, and 609 million video views during the 2024 Paris Olympics (Koos, 2024). In total, World Aquatics digital community has a total of 5.6 million fans across the globe, with 1.1 million new fans during the Paris 2024 Olympics. This recent surge prompts the question of what has changed in swimming and what the sport’s future success might look like. Olympic swimming has always had more success than other swimming competitions, but the social media engagement described by World Aquatics is far beyond what swimming has typically seen.

As an Olympic sport, swimming has been a part of every summer Olympic Games since the first modern Olympics in 1896. Just as swimming’s popularity as a sport was increasing, changes to sport’s rules were being implemented. For example, women began competing in Olympic swimming events in the early 1900s. Women were first allowed to officially compete in the Olympics for the first time at the 1912 Stockholm Games, where they swam the 100 meter freestyle and the 4×100 meter freestyle relay (Şarvan & Coşkun, 2023). At these Games, 27 women competed in the events. This was 22.5% of the total swimmers during the Games (Takata, 2024). The percentage of women in swimming reached 46.1%, the highest until 2012, during the 1972 Olympics. Since then, the female to male ratio has been largely similar, with the Tokyo 2020 Games being composed of 45.5% female swimmers and 54.5% male swimmers. The Tokyo Games were also the first Olympic Games to offer the every race to both men and women athletes, allowing women to compete in the 1500 meter freestyle and adding the 800 meter freestyle for the men (Takata, 2024).

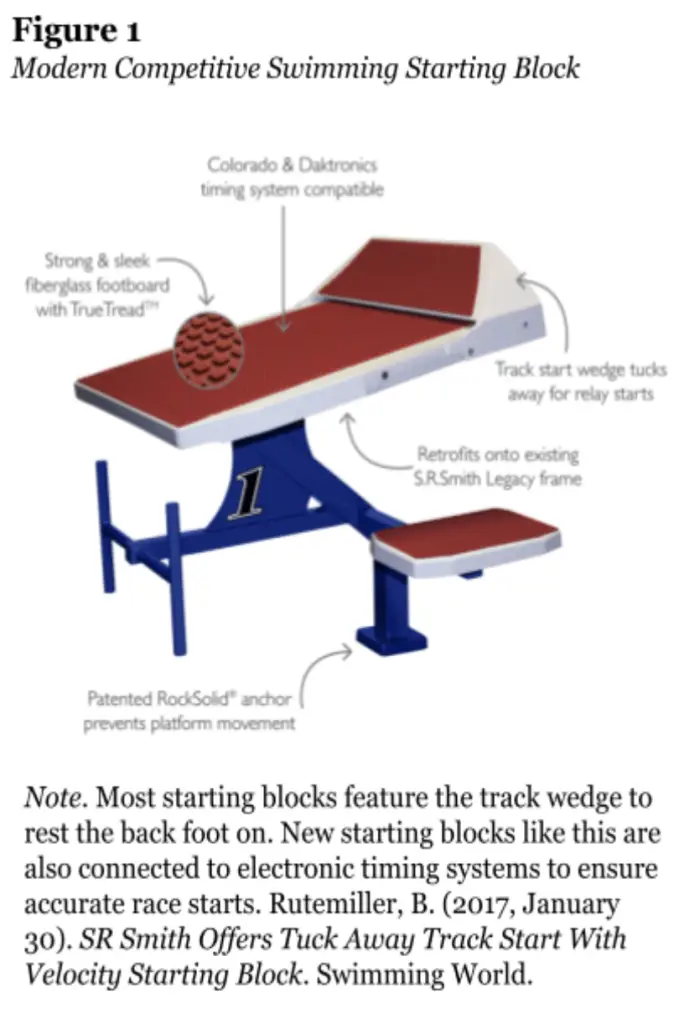

Şarvan & Coşkun (2023) outlined how numerous changes to the sport, including some major rule implementations by the Fédération Internationale de Natation (FINA) have impacted the sport. These have included various changes to the stroke techniques, distance allowed underwater, false start procedure, and starting block structure . In 1998, FINA, also known today as World Aquatics, introduced a new rule requiring swimmers to surface above water no further than 15 meters past the wall, coming off the start and turns. Rules around false starts have become more strict: while rules used to permit athletes to have three false starts before a disqualification, the governing body changed the rule in 2001 to make just one false start result in an immediate disqualification and inability to race. More recently, starting blocks have been changed to include a wedge that the athlete’s back foot can rest on and push off from. While it’s not mandated for all swimming competitions, it is a suggestion from FINA, so most new facilities have starting blocks with the footrest (figure 1). Every Olympics since Beijing 2008 has included wedged starting blocks. Researchers have found that FINA’s rule changes to swimming competitions such as those to the start, underwater, and technique directly affect the lap time and record developments in the Olympic Games (Şarvan & Coşkun, 2023).

Pool swimming has races ranging in distance from 50 meters all the way to 1500 meters, while open water swimming races range from 5km to 25k (The Definitive Guide to Open Water Swimming, 2025). While all of the pool distances are swum at the Olympics, the only Olympic open water distance is 10k. At the Olympics, open water races are traditionally competed in lakes, rivers, or oceans. Swimming wasn’t competed in pools at the Olympics until the London 1908 Games (The History of Olympic Swimming, 2018). The Olympic pool spans 50 meters, making the shortest race, the 50 meter, just a single lap and the longest race, the 1500, 30 lengths.

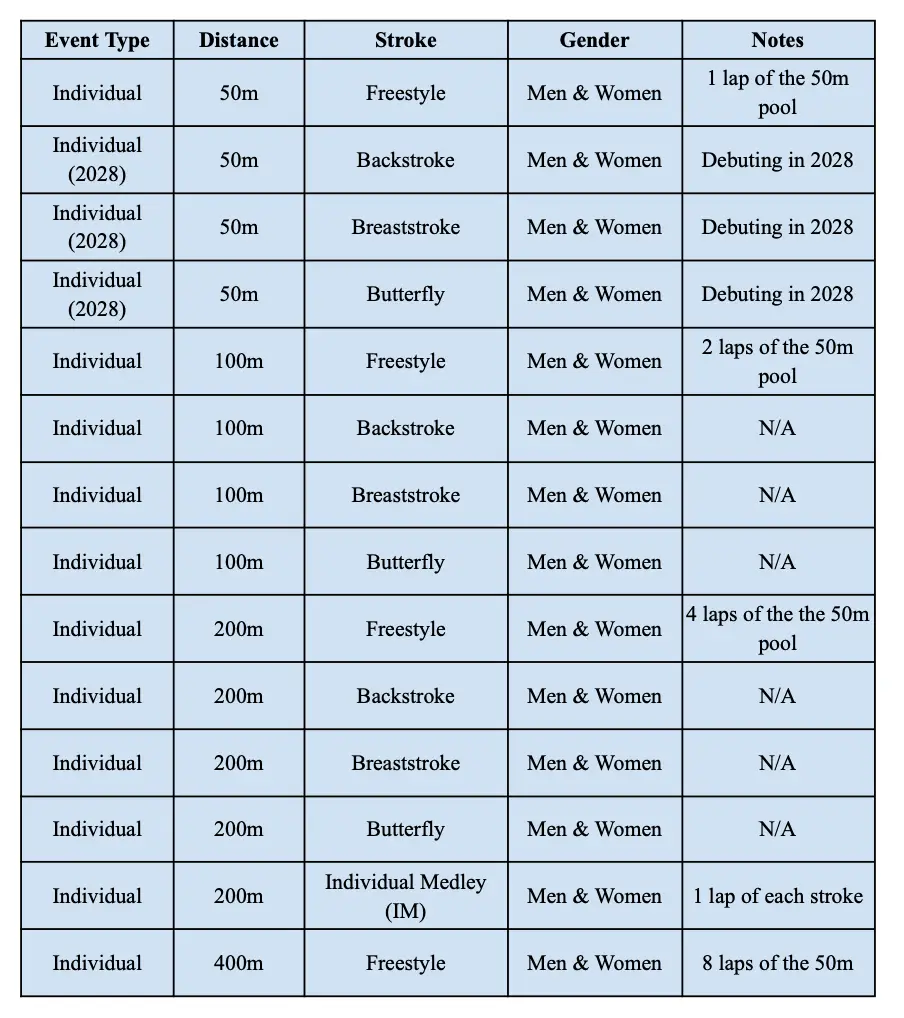

Olympic Swimming Events

At the Olympics, athletes compete in all four strokes: butterfly, backstroke, breaststroke, and freestyle. An additional event called the Individual Medley, or IM for short, is also competed. The IM contains just one or two laps of each stroke, depending on the distance, since both the 200 meter IM and 400 meter IM are swum. The strokes butterfly, backstroke, and breaststroke are raced in both the 100 and 200 meter distances, with 50 meter distance becoming a new addition to the Olympics in the 2028 Games (Folsom, 2025). Freestyle is raced in the 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, and 1500 meter distances. An important part of Olympic swimming is the relays. Countries can put together relays with the best four athletes on their team to represent their country. All relays have four legs to them, and range from 200 meters to 800 meters. The four relays competed at the Olympics are the 200 freestyle relay, the 400 freestyle relay, the 800 freestyle relay, and the 400 medley relay, where each swimmer swims two laps of each stroke. An additional relay, the mixed medley relay, was added in 2020. See Appendix A for a visual breakdown of the Olympic swimming events. The wide variety of distances and strokes makes swimming a unique sport.

History of Track & Field

Track & field has a rich history dating back to the very first ancient Olympic Games in Athens Greece, which took place every four years from 776BC to at least 393AD (Welcome to the Ancient Olympic Games, 2025). In that very first Olympics, track and field events including running, javelin, long jump, and shot put were some of the limited sports competed. Running itself dates back even further;as a vital and innate skill for hunter gatherers (One Foot in Front of the Other, 2015). Persistence hunting allowed for humans to outlast their new meal, following their prey for long distances. Humans have been naturally adapted for efficient long-distance running: our 2.4 million sweat glands help regulate body temperature, while the springy tendons and muscles in our legs store and release energy to keep us moving smoothly between strides (Insider Tech, 2008). Running is also arguably one of the simplest sports, requiring no equipment, so it’s not surprising that it was the earliest sport. Besides running’s history in the Olympics, running has also been a part of ancient stories, like that of Pheidippides, whose story was the inspiration for the marathon long-distance running event (One Foot in Front of the Other, 2015). His story was important in presenting long-distance running as a courageous and patriotic act, though not without danger (he died during the end of his run).

Closely connected to distance running is cross country. This sport involves running longer distances over natural landscapes, not a track. Unsurprisingly, the world’s top distance runners on the track are also top ranking at cross country. Sometimes, obstacles like hills, hay bales, and mud pits are featured on the course. Cross country was an event in the Olympics from 1912 to 1924 (Cross-Country Running, 2024), but hasn’t been in the Games since then, although there have been discussions of reintroducing cross country as a Winter Olympic sport (Dunbar, 2024).

Although running persisted through the ages in various forms, its popularity as a sport and fitness trend didn’t fully return until the 1900s. Specifically, the “jogging boom” in the 1970s (Lathan, 2023). This sudden interest in jogging was sparked by two main figures: New Zealand coach Arthur Lydiard and University of Oregon track coach Bill Bowerman. Together, these coaches successfully spread the idea that jogging was a great way to exercise and stay fit. Ken Cooper supplemented their ideas with his own published book “Aerobics,” which brought up the importance of running for cardiovascular fitness. Similarly, Bowerman wrote his own best-selling book in 1966 titled Jogging. The interest in running was also fueled by the American Olympic victory in the marathon by Frank Shorter in 1972. Shorter remains one of only three Americans to have won the Olympic marathon, with the other two victories coming in 1904 and 1908. Outside of his victory, Shorter popularized running by opening up professional opportunities in running and advocating for clean sport (Futterman, 2022). During the running boom, roadraces, shoe sales, and jogging for exercise all increased. By the late 1980s and early 1990s, the boom slowed down as running became more established.

While the running boom showed steady growth for two decades, it began to decline in the mid 2010s (Bachman, 2016). This decline was especially noticeable among younger adults, as millennials started to favor other forms of exercise including cycling, cross-fit, and boutique classes like pilates. Running has remained popular overall, but participation in races and regular jogging dropped from its peak. This reflects the shift in fitness culture towards more social activities, like fitness classes. Jogging is still common, but the running community moved away from a competitive and race-focused identity toward a broader view with more emphasis on well being.

It’s unclear what the future holds for running. Major changes came with Covid-19 pandemic, with research showing that running gained popularity during the Covid-19 pandemic. In a survey across 10 countries, about 40 percent of people see themselves as runners, and of those, 30 percent run at least once a week (Recreational Running Consumer Research Study Nielsen Sports, 2021). However, since this study was conducted in 2021, some people may have since stopped running after pandemic restrictions eased and routines changed. Additionally, future generations’ level of activity could impact the popularity of jogging. Members of Generation Z have been found to exercise the most compared with Generation X, Millennials, and Baby Boomers (Erikson, 2024). Conversely, there are concerns for the well-being of the younger Generation Alpha members since they’ve grown up fully immersed in a digital world (Generation Alpha: The Real Picture, 2021). The lasting impact of the jogging boom will depend on how well future generations maintain active lifestyles with competing interests and digital distractions.

Today, track and field remains a niche sport in year-round popularity but a major event sport around global competitions like the Olympics. While the 2023 World Championships drew in 280k viewers and the 2024 World Indoor Championships drew in just 95k viewers on NBC (Track and Field Ratings, 2024), 5.2 million people viewed the 2024 US Olympic Team Trials on NBC (Karp, 2024). That is 18 times more viewers for the US Team Trials than World Champs, despite the competitions being just 1 year apart. Similarly, the 2024 NCAA Track and Field Championships drew a total of 1.7 million viewers across multiple days of broadcasts (Chavez, 2024). All 2024 viewership numbers exceeded the 2023 NCAA Championships. Overall, viewership was much higher than the 1.178 million for the 2022 Championships. This shows that track and field gets some attention during big national and college events, leading into the even bigger audiences at the Olympics.

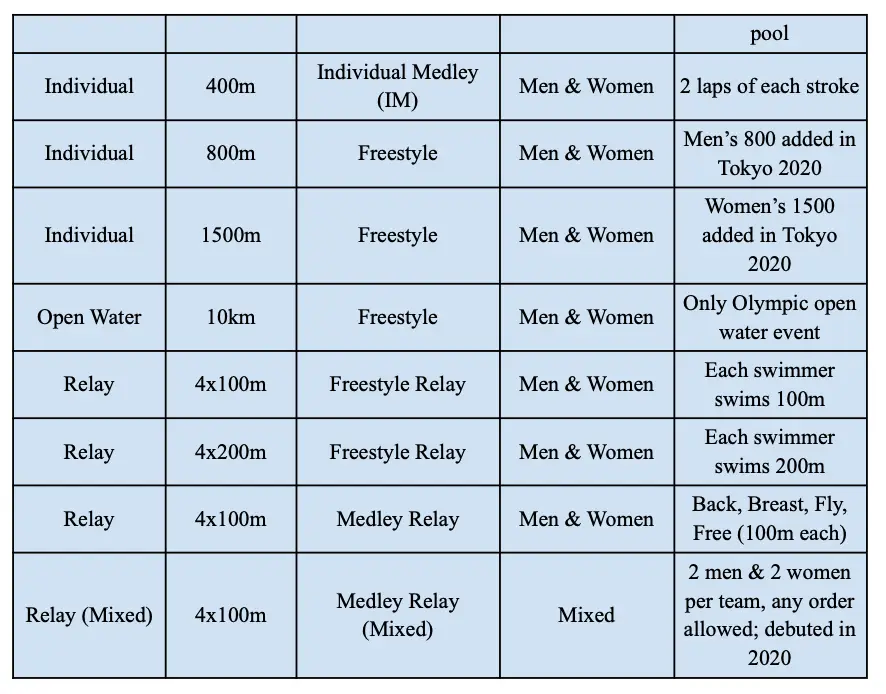

Olympic Track & Field Events

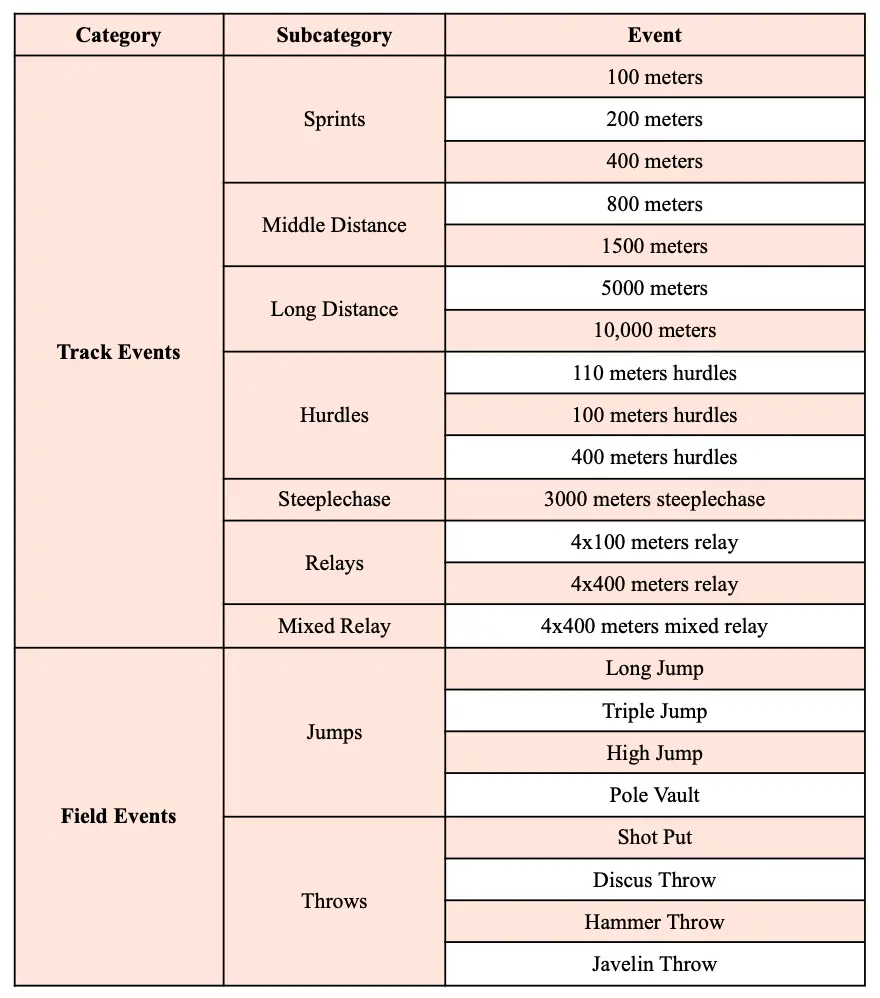

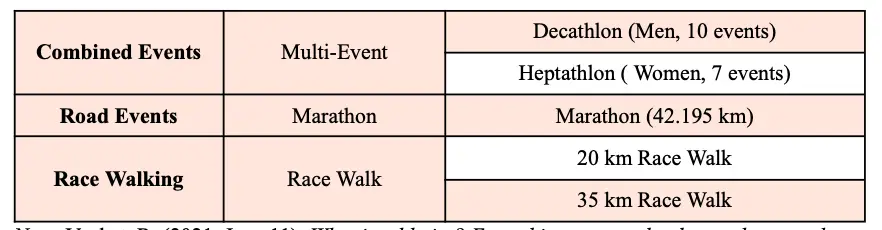

Track and field has an even more diverse event lineup than swimming. The events can be broken down into three major categories: running, jumps, and throws. These categories can also be broken down further. Running includes sprints, distance, and hurdles while jumps include both horizontal and vertical jumps. Track and field also offers relays and combined events, which are multi-discipline competitions where athletes compete in a series of different track and field events over one or two days. For the combined events, the women compete in the Heptathlon (7 events) while the men compete in the decathlon (10 events). All other events except the hurdles are the exact same for men and women. The sprint hurdles are 110 meters for men but just 100 meters for women. See appendix B for a list of all the Olympic track and field events.

Track & field wasn’t an Olympic sport for women until 1928 (Holmes, 2021). Even then, meet organizers only introduced limited events: just the 100m, 4 x 100m relay and 800m. The 800m was removed until 1960 after the 1932 Olympics when some female athletes collapsed after the race. It wasn’t until the 2008 Beijing Games that men and women competed in the same events, once the 3000m steeple chase was added. Still, women aren’t offered the decathlon, instead the heptathlon.

Olympic Fandom

The modern Olympics never fail to gain the world’s attention every four summers (Bittle, 2021). Commercials, billboards, documentaries, and all sorts of Olympic media are everywhere in the months leading up to the Games. People who have never watched sports like swimming, track & field, and gymnastics often find themselves enraptured by the competition and national talent in these sports. For example, an Australian study found that viewing someone from your country competing in the Games can create a strong sense of national pride (Hendley, 2024). Additionally, the authors found that watching the incredible athletic performances can provide feelings of joy and inspiration (Hendley, 2024). The media, the excitement, and the emotion all help explain why the Olympics draw so many viewers. However, this high level of interest often fades once the Olympics are over, and many of these sports struggle to keep the same audience for other competitions (Campbell, 2024).

Even though millions tune in to cheer on their favorite athletes, most viewers remain spectators rather than participants. The idea that viewing elite athletic performances drive mass participation is largely a myth. A study done after the 2020 Tokyo Games found that about 70% of people were not motivated to exercise after watching the Olympics (Vukovic, 2021). Those who reported that the Olympics did not make them want to exercise cited reasons like time, age, injury, and cost barriers. The minority who reportedly did feel inspired to exercise said it was because of admiration for athletes and reminder of health benefits.

Researchers have looked into how to get more children involved in sports, and they found that boys are more likely to be influenced by successful athletes, while girls are more likely to look to parents, teachers or peers as role models (Vescio et al., 2005). So, when looking into how to get the children involved in sports after the Olympics, creating role models out of athletes would be more successful for boys.

While the Olympics spark huge interest and national pride every four years, for sports like swimming and track that excitement often doesn’t last much beyond the Games themselves (Campbell, 2024). Many fans tune in during the Olympics but don’t stick around for other competitions. To understand why, it’s important to look at how people become fans and what motivates them to follow sports over time. Researchers understand fandom as a complex mix of emotional connection, identity, and social belonging centered around a particular sport, athlete, or team (Mastromartino et al., 2017). Understanding fandom helps explain both the surge in attention during big competitions and the challenges sports face in maintaining a steady fan base year-round. It is especially important to understand for non-revenue sports, where marketers and organizers must work harder to keep fans engaged with limited media coverage and fewer high-profile events (James & Ross, 2004).

Sports Fandom & Psychological Connection

Sports fans are people that enjoy watching and following sports, teams, and athletes. Through repeated supported behaviors, they express their fan identity (Wang, 2020). Being a fan of sport is so common because being a fan actually meets some of their basic psychological needs like social connection, belongingness, and identity (American Psychological Association, 2025). There’s no single personality profile of a sports fan, but fans tend to be slightly more extroverted. Despite that, people of all types follow all kinds of sports (American Psychological Association, 2025). Even family fans might enjoy violent sports like wrestling or MMA. Being a fan brings groups of people together through a common passion, creating a shared identity and community. Beyond just watching a game, fandom offers rituals, shared experiences, and traditions that strengthen these social ties and contribute to a fan’s personal identity (Media Culture, 2024). From tailgating outside a sporting event to passionately debating stats online, sports fans express their dedication in many ways.

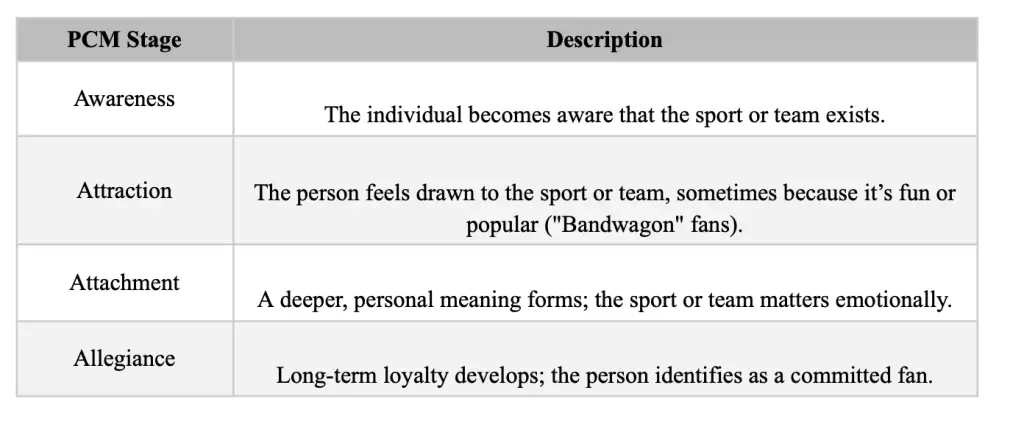

Part of developing fans of a sport comes down to understanding how people form psychological connections. The Psychological Continuum Model (PCM; Funk & James, 2001; 2006) explains that this happens through four stages: awareness, attraction, attachment, and allegiance (figure 2). At first, someone simply becomes aware that a sport or team exists. If the sport or team seems fun or popular, they may feel attracted to it. Over time, the connection can grow into a personal attachment, where the team holds meaning beyond entertainment. The final stage is allegiance, where fans stay loyal over time, even during tough periods.

Funk, D & James, J (2001) The Psychological Continuum Model: A Conceptual Framework for Understanding an Individual’s Psychological Connection to Sport, Sport Management Review, 4:2, 119-150

Understanding how fans get motivated to follow sports in the first place is also important. James and Ross (2004) surveyed various sports fans to determine what key motivations may be, and if they vary from sport to sport. For example, sports like figure skating and gymnastics attract fans through aesthetics and appreciation of skill, while team sports like basketball and baseball are more connected to emotional motives such as drama, team affiliation, and vicarious achievement (James & Ross, 2004). Overall, across baseball, softball, and wrestling, entertainment was rated the highest while empathy was lowest. For these three non-revenue sports, general sport-related motives (entertainment, skill, drama, team effort) were rated higher than self-definition motives (achievement, empathy, team affiliation) and personal benefit motives (social interaction, family). The information about the motivations of fans of these sports can help marketers promote nonrevenue sports to support increased attendance and engagement. By focusing on athletes’ skills, the drama of the sport, and the entertainment experience of these sports, marketers can attract and retain fans, even for nonrevenue sports that typically receive less attention.

Social influences, entertainment value, situational factors like team success or promotions, and emotional investment all play a role in helping people move along this continuum. Not every person reaches the highest stage of allegiance, and progression can move backward as well as forward. This helps explain why so many fans follow swimming and track during the Olympics, when national pride and promotion are at their peak, but then lose interest afterward. These fans may only reach the awareness or attraction stages, without developing the deeper connection needed to stay engaged between Olympic cycles. Most “bandwagon’ fans don’t develop past the attraction stage (Funk & James, 2001).

Understanding Fandom in Swimming & Track and Field

While it’s possible that viewers watch swimming or track during the Olympics simply because it airs at a convenient time, one study suggests that prime-time coverage might not have an impact on creating fans (Li et al., 2018). The researchers analyzed Twitter following for several National Governing Bodies including USA swimming. They found that posting more frequently correlated with more followers, about 18 per post, but also that NBC’s prime-time broadcast schedule, athlete gender, and total medals won didn’t significantly impact follower growth. Only gold medals led to a substantial increase, highlighting that dominance draws more fans than general success. USA Swimming, for instance, gained about 41,000 followers after winning 16 golds in the 2016 Rio Olympics. The fact that only gold medals had a significant impact on follower count suggest that casual viewers are more drawn to US excellence than the sport itself. Fans keep watching throughout the Games because the events are exciting and the media highlights U.S. success. However, they don’t continue following swimming or track after the Olympics end. Track and swimming organizations should focus on how to develop Olympic “bandwagon” fans into true fans who form lasting attachments and allegiance to the sport.

Barriers & Constraints of Swimming and Track & Field Fandom

Both track and swimming have issues that prevent long-term fandom. These issues can be broken down into two large categories: the built experience (venue, structure, and tech) and the narrative and emotional connection (storylines, identity). The Olympics naturally provides “fixes” for some of these issues. Most venues for track and swimming aren’t designed for spectators– but the Olympic stadiums and natatoriums are. Similarly, the Olympics are able to use advanced technology that are rarely available at other competitions to improve the spectator experience. And while track and swimming often lack the team rivalries that keep fans invested, the Olympics create national rivalries by uniting athletes under their countries, giving fans a clear side to root for. Understanding these challenges is key to finding ways to grow and sustain fandom beyond the Olympic spotlight.

Venue and Spectator Experience Limitations

Swimming struggles to keep fans engaged at smaller meets, even though it draws huge crowds during events like the Olympics and World Championships. Outside of those big meets, the stands are often empty (Derom et al., 2023). A big part of the problem is that many swimming facilities aren’t built with spectators in mind. They’re designed for training or recreation, not for watching a meet. That leads to low entertainment value, limited crowd energy, and little reason for people to stay interested. Even experienced swimmers in the crowd can feel disconnected during races. One study found that many fans at swim meets are mainly there to admire the aesthetics of the sport, such as clean strokes or fast finishes, but that doesn’t always mean they’re mentally or emotionally invested (Derom et al., 2023). Just liking the sport isn’t enough to make someone enjoy going to the event.

The success of the 2024 U.S. Olympic Swimming Team Trials proved the importance of a well designed stadium. Taking place in Lucas Oil stadium, USA Swimming designed the venue with the spectator experience in mind. Since it’s primarily a football stadium, there was lots of construction that went into installing the pool– but all the hard work was worth it when the meet broke the swimming attendance record with twenty-two thousand spectators (Rosado, 2024). This venue made for a better experience for both athletes and spectators: the athletes were able to experience the energetic atmosphere from a large energetic packed stadium and the spectators were able to watch elite performances all while having access to traditional sports venue amenities that swimming fans don’t usually get. It also made for a better experience for viewers at home. They experienced the same high energy crowds and athletic performances on television. Future meet organizers should look into hosting meets at larger venues like major sports stadiums. NCAA Championships, US Nationals, and TYR Pro Series could be held in better venues that allow for a better spectator experience.

Similar to swimming, the venues for track could also benefit from improvement. While football, soccer, and baseball stadiums offer a wide variety of food, drinks, and convenient vending options, many track venues fall short in this area. Fans often have limited access to refreshments, with few choices beyond basic concessions. Collegiate track “stadiums” also can’t compare with US collegiate football stadiums, which are as big if not bigger than NFL stadiums. If the venues aren’t spectator friendly, people won’t want to watch the meet, no matter how talented the field of competitors are.

Structural and Format Barriers (Lack of Rivalries)

Additionally, since swimming and running aren’t team sports in the same way that football, basketball, baseball, and soccer are, less rivalries exist. Rivalry creates a clear ingroup vs outgroup for sports fans, which strengthens loyalty to a team (Piercy & Kiser, 2024). The Olympics turns these individual sports into team sports by uniting athletes under their country. This in turn allows some national rivalries to exist, such as the USA swimming rivalry vs Australia (Binner, 2024) and the running rivalry between USA and Jamaica in the sprints (Bowman, 2024). If swimming and running are able to create and hype up more athlete rivalries, fans may be more engaged to follow the sports. The 2024 rivalry between world leaders in the 1500m Josh Kerr and Jacob Ingebrigtsen made the 2024 1500 Olympic final an exciting race for fans that have been following the rivalry for the whole year (Pells, 2024). In both swimming and running, the lack of rivalries contributes to the lower fanship outside of the Olympics. Sports marketers and even professional sport brands like Nike, New Balance, Speedo, and Arena should look to generate and promote any rivalries that may occur between their sponsored athletes.

Another structural problem prominent in both swimming and running is athletes’ hesitancy to race often. At the high level of performance that most professional athletes compete at, training and peaking for certain races requires the perfect build up and taper of workout volume (Wang, 2023). Because of this, swimmers are often only in peak shape once, maybe twice a year. Since athletes usually want to make the Olympic or World Champs team every year, the meet they taper for is usually US team trials. Oftentimes, US swimmers actually end up swimming faster at Olympic/World team trials than at the actual Olympics or World Championship meet that takes place a month or two later (Mering, 2016). This is because the athletes plan their taper to maximize their chances of making the team, and don’t have enough time between trials and the actual event (if they made the team) to build back their training and then taper down again. In order to change this, swimmers would need to normalize more frequent racing and potentially less intense training. This would likely result in slower performances, so it’s unlikely athletes would choose to race more.

This phenomenon is more talked about in swimming than running, but is still present in Track and Field. In track, top athletes are still training very hard, going to high altitude training camps and working out multiple times again. Racing, especially distance races (like the 1500/mile, 5k, 10k), are very physically demanding races. Athletes would struggle to compete in those races every week, like other sports like football, basketball and baseball regularly do. Still, track & field does have more professional racing opportunities than swimming. The Wanda Diamond League, Grand Slam, and other smaller competitions provide chances for the world’s best track and field athletes to race against each other multiple times a year (Sim, 2025). Meanwhile, the only comparable competition that swimming offers would be the TYR Pro Series, which gets a few US Olympians every so often, but is mostly attended by NCAA athletes and top high schoolers. In 2019 the International Swim League (ISL) was created, but failed due to geopolitical events like the war in Ukraine and other fiscal mismanagement, and no longer exists (Ross, 2025). These natural limitations to athletes’ willingness to compete frequently in both swimming and running make it difficult to maintain a consistent fanbase.

Technology Use and Accessibility (Swimming and Running Tech Enhancements)

New technology has also helped fans get engaged with the sport and athletes (Bi et al., 2019). Both swimming and running can use technology to create a more immersive experience for fans. Modern swim broadcasting on television already uses underwater cameras to show the swimmers’ flipturns and dives while also showing the swimmer’s speed in meters per second. By displaying the athletes’ speed, fans can understand just how much faster some athletes can finish their races compared to others. Additionally, larger and improved jumbotrons can show athlete’s reactions to winning, lap splits, and close-up footage can bring fans in the stands closer to the action (Kraus, 2014). While some natatoriums have good scoreboards/jumbotrons, swim organizations should consider choosing a venue with the screen in mind. The 2024 Olympic pool venue (Paris La Defense Arena) boasted a 1400 square meter screen while the location of the men’s 2024 NCAA championship, Indiana University’s pool, only had a 16 ft x 59 feet screen. (Schwarb, 2019).

Track and field can also use technology to enhance the spectating experience for fans (Bi et al., 2019). From live athlete heart rate monitoring to pace lights around the track, technology helps fans follow races and understand splits. In distance running especially, the interaction between fans and athletes is very short. Bi et al. (2020) found that allowing fans to follow online splits and gps tracking makes them feel more connected to the runners. Additionally, knowing the runners goal strengthened fan engagement. Participants explained that knowing the goals, physical, and emotional effort put into the training by their runner made them deeply connected to their runner’s success. This can be applicable to professional running: while fans might not know the athletes personally, through social media and general knowledge, they can understand the rigorous training that these athletes put themselves through to maximize their performance. This helps explain why projects like Breaking 2 and Breaking 4 foster good fan response: showcasing the hard work and extreme lengths that athletes, coaches, and sponsors are going through just shaving off a few seconds resonates with people. This finding also suggests that the fitness social media app Strava is a tool professional athletes should be active on. This app allows athletes to share their daily runs to the feeds of other athletes. So, more media attention on specific workouts and training that athletes’ do, like those shared on Strava, could help get fans more invested in professional athletes’ success.

Narrative Limitations and Difficulty Connecting to Athletic Feats

Both swimming and running evidently have problems with keeping fans engaged in the sport. Creating fan connection to athletes and specific storylines is crucial to developing fans of sports (Shain, 2023). Swimming in particular struggles to create these storylines that allow fans to get engaged with the sport. While running races often have impressive time-barrier breaking performances/goals, swimming isn’t able to create such exciting stories. Famous in distance running was the sub 2-hour marathon attempt by Kenyan distance runner Eliud Kipchoge in 2017 and the more recent female sub 4-minute mile attempt by world record holder Faith Kipyegon in 2017 (Boswell, 2025). Both were big projects run by Nike that were televised and advertised well. Although neither initially succeeded in actually breaking their respective time barrier, they succeeded in generating massive global attention and excitement, ultimately helping fanship of the sport (Rogers, 2018).

Part of the problem may be that the swimming talent is harder to understand for non-swimmers. While most people understand that running a sub 4-minute mile is incredibly fast (15 mph), less understand just how fast the world record holders are swimming in their events. Information about the sport should be included by marketers in advertisements and announcers during competitions. If more people are able to understand swimming, they may find themselves more drawn to the sport and the incredible performances being swum by the world’s top swimmers.

National Identity and Patriotism as Emotional Anchors

Another factor that helps explain Olympic fan engagement is the strong connection people feel toward their national teams. Brown et al. (2020) found that strong fandom during the 2018 Winter Olympics was connected to increased feelings of nationalism and patriotism. The study defined nationalism as a belief in the superiority of one’s nation over others and patriotism as positive feelings about one’s country, like pride and support. They found that fans of their National Olympic team were the most engaged in sport media compared to general sport fans and fans of the winter Olympics as an event (Brown et al., 2020). This reflects the study’s finding that national team fandom was the strongest predictor of media consumption across all formats. This helps explain why largely individual sports like swimming and running succeed during the Olympics when national identity is emphasized, but maintain that audience after the Games end, and athletes return to their individual competition schedule.

Conclusion

Track and field and swimming are some of the Olympics most watched sports, but fail to maintain a consistent fanbase outside of the Games (Campbell, 2024). Both sports have rich histories, dating back to centuries of competition and recreation (Athanasiou, 2024; Sears, 2015). Analyzing why track and swimming have these issues with fandom is important for athletes, the media, sports organizations, and psychologists hoping to better understand sports fandom. For both sports, national pride sparks short-term fandom but rarely translates into lasting allegiance. Fans likely don’t move past the attraction stage of the PCM (Funk & James, 2001): the media attention and national talent draws them into the sport, but their interest fades once the Games are over. True fandom requires connection, identity, and continuity. Swimming and running lack the venues, meets, and storylines to build lasting fan communities. This pattern highlights a broader truth about sports fandom: attention built on rare spectacle and national pride cannot substitute for the consistent community and identity that other sports maintain. The future of swimming and track fandom may depend on whether these sports embrace technology, host competitions in fan-friendly venues, build rivalries, and craft storylines that keep audiences engaged long-term.

This research is limited by its qualitative approach. Relying primarily on news articles, reports, and media coverage to understand trends in swimming and track fandom, it fails to capture the personal experiences and motivations of the fans themselves. Additionally, the lack of data surrounding swimming and track viewership makes it difficult to quantify the difference in fandom between the Olympics and other competitions. While other sports have viewership data about major competitions published or accessible on their websites, both USA Swimming and USA Track and Field do not share this information. The absence of publicly available viewership data may also suggest that these organizations place less emphasis on tracking or promoting fan engagement compared with other sports. It’s important to continue to understand these gaps in fandom as doing so can create opportunities for sports to strengthen fan engagement. Future research could use fan surveys to quantify viewership differences between the Olympics and other major events. This study highlights that without intentional strategies to engage fans, even historic and elite sports risk losing their audience once the spotlight fades

Appendix A

Olympic Swimming Events

Table A1: Olympic Swimming Events

Post, J. J. (2024, August 11). How does Olympic swimming work? Events, schedule, scoring –

ESPN. ESPN.com; ESPN.

Appendix B

Olympic Track and Field Events

Note. Venkat, R. (2021, June 11). What is athletics? Everything you need to know about track and field. Olympics.com; International Olympic Committee.

References

American Psychological Association. (2025, July). Speaking of psychology: The psychology of sports fans, with Daniel Wann, PhD. American Psychological Association. [https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/sports-fans](https://www.ap a.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/sports-fans)

Athanasiou, C. (2024, October 12). Did ancient Romans exercise to keep fit? Roman Empire Times. [https://romanempiretimes.com/did-ancient-romans-exercise-to-keep-fit/](https://romane mpiretimes.com/did-ancient-romans-exercise-to-keep-fit/)?

Bachman, R. (2016, May 5). Has the running boom peaked? It may be millennials’ fault. MarketWatch. [https://www.marketwatch.com/story/has-the-running-boom-peaked-it-may-be-millennial s-fault-2016-05-05](https://www.marketwatch.com/story/has-the-running-boom-peaked-i t-may-be-millennials-fault-2016-05-05)

Bi, T., Bianchi-Berthouze, N., Singh, A., & Costanza, E. (2019). Understanding the shared experience of runners and spectators in long-distance running events. 1–13. [https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300691](https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300691)

Binner, A. (2024, July 22). Six swimming stars reveal what the USA versus Australia rivalry means to them ahead of Paris 2024. Olympics.com; International Olympic Committee. [https://www.olympics.com/en/news/usa-australia-swimming-rivalry-olympics-lilly-king-michael-phelps](https://www.olympics.com/en/news/usa-australia-swimming-rivalry-olympics-lilly-king-michael-phelps)Beyond the Olympics: Sustaining Fandom in Swimming and Track & Field 32

Bittle, J. (2021, July 10). Why are people obsessed with the Olympics?. Popular Science. [https://www.popsci.com/science/olympics-fans-psychology/](https://www.popsci.com/science/olympics-fans-psychology/)

Boswell, R. (2025, July 10). Faith Kipyegon shattered the 1500m world record, again – but was her Breaking4 failure a bigger success? Runner’s World. https://www.runnersworld.com/uk/about/a65252420/kaith-kipyegon-breaking4-success

Bowman, E. (2024, August 10). In Paris, Jamaican sprinters backslide in Olympic track rivalry with U.S. NPR. [https://www.npr.org/2024/08/10/g-s1-16218/jamaica-us-track-rivalry-olympics](https://www.npr.org/2024/08/10/g-s1-16218/jamaica-us-track-rivalry-olympics)

Campbell, M. (2024, September 26). Track and field’s viewership problem in non-Olympic years requires revamped marketing strategy. CBC. [https://www.cbc.ca/sports/olympics/summer/morgan-campbell-track-and-field-audience-1.7334117](https://www.cbc.ca/sports/olympics/summer/morgan-campbell-track-and-field-audience-1.7334117)

Canadian Equality Consulting. (2024, July 28). Canadian Equality Consulting. CEC. https://canadianequality.ca/uniting-the-world-how-the-olympics-foster-inclusion-and-peace/

Chavez, C. [@chrischavez]. (2024, June 12). Here is the TV viewership information for the 2024 NCAA track and field championships that took place this past weekend in Eugene via @paulsen_smw [Tweet]. X. [https://x.com/ChrisChavez/status/1800863277980819725](https://x.com/ChrisChavez/status/1800863277980819725)

EBSCO Information Services. (2024). Cross-country running. [https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/sports-and-leisure/cross-country-running](https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/sports-and-leisure/cross-country-running)

Derom, I., Taks, M., Potwarka, L. R., Snelgrove, R., Wood, L., & Teare, G. (2023). How pre-event engagement and event type are associated with spectators’ cognitive processing at two swimming events. *Journal of Global Sport Management, 10*(1), 84–108. [https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2023.2197918](https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.202 3.2197918)

Dunbar, G. (2024, August). Talks to add cross-country running and cyclocross to Winter Olympics, World Athletics’ Coe confirms. AP News. [https://apnews.com/article/2024-paris-olympics-coe-crosscountry-cyclocross-winter-67beda9f3a30d5baa3d0d6177fbea2b0](https://apnews.com/article/2024-paris-olympics-coe-crosscountry-cyclocross-winter-67beda9f3a30d5baa3d0d6177fbea2b0)

Erickson, M. (2024, April 22). Research shows Gen Z exercise more than any other Aussies. Adelaidenow; The Advertiser. [https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/lifestyle/gen-z-exercise-more-than-any-other-aussies/news-story/d9653377e74a423a6c4fd88147e482fc](https://www.adelaidenow.com.au/lifestyle/gen-z-exercise-more-than-any-other-aussies/news-story/d9653377e74a423a6c4fd88147e482fc)?

International Olympic Committee. (2024, December 5). Around 5 billion people – 84 per cent of the potential global audience – followed the Olympic Games Paris 2024. Olympics.com; International Olympic Committee. https://www.olympics.com/ioc/news/around-5-billion-people-84-per-cent-of-the-potential-global-audience-followed-the-olympic-games-paris-2024

Folsom, M. (2025, April 10). World aquatics announces 50s of stroke added to 2028 Olympics. SwimSwam.[https://swimswam.com/world-aquatics-announces-50s-of-stroke-added-to-2028-olympics/](https://swimswam.com/world-aquatics-announces-50s-of-stroke-added-to-2028-olympics/)

Funk, D., & James, J. (2001). The psychological continuum model: A conceptual framework for understanding an individual’s psychological connection to sport. *Sport Management Review, 4*(2), 119–150. [https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523(01)70072-1](https://doi.org/10.1016/S1441-3523%2801%2970072-1)

Futterman, M. (2022, September 10). How a marathon win 50 years ago kick-started the “running boom.” Nytimes.com; The New York Times. [https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/10/sports/frank-shorter-running-boom.html](https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/10/sports/frank-shorter-running-boom.html)

Generation Alpha: The real picture. (2021). Gwi.com.[https://www.gwi.com/reports/gen-alpha](https://www.gwi.com/reports/gen-alpha)?

Hendley, S. (2024, July 24). Why even non-sports fans get gold-medal fever. Dailytelegraph; Daily Telegraph. [https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/lifestyle/why-even-nonsports-fans-get-goldmedal-fever/news-story/5105e53d762e23c4b0ea8ce52b323e30](https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/lifestyle/why-even-nonsports-fans-get-goldmedal-fever/news-story/5105e53d762e23c4b0ea8ce52b323e30)?

Holmes, K. (2021, July 28). An Olympics timeline – women’s running – RunYoung50. RunYoung50. [https://runyoung50.co.uk/olympics-timeline/](https://runyoung50.co.uk/olympics-timeline/)

Insider Tech. (2008). How humans evolved to become the best runners on the planet.

Karp, A. (2024, June 25). USA track & field trials has best audience since ’12. Sports Business Journal. [https://www.sportsbusinessjournal.com/Articles/2024/06/25/usa-track-and-field-nbc-viewership](https://www.sportsbusinessjournal.com/Articles/2024/06/25/usa-track-and-field-nbc-viewership)

Keith, B. (2022, August 3). US swimming nationals highlight show draws 572,000 viewers on NBC. SwimSwam. [https://swimswam.com/us-swimming-nationals-highlight-show-draws-572000-viewers/?utm_source=chatgpt.com](https://swimswam.com/us-swimming-nationals-highlight-show-draws-572000-viewers/?utm_source=chatgpt.com)

Koos, T. (2024, September 11). World aquatics smashes digital records at #Paris2024 Olympic Games. World Aquatics. [https://www.worldaquatics.com/news/4111319/world-aquatics-digital-communications-fans-audiences-record-setting-analytics-paris-2024-olympics-jeux-olympiques](https://www.worldaquatics.com/news/4111319/world-aquatics-digital-communications-fans-audiences-record-setting-analytics-paris-2024-olympics-jeux-olympiques)

Kraus, T. (2025). The effect of Jumbotron advertising on the experience of attending major league baseball games. Umsystem.edu.[https://hdl.handle.net/10355/45673](https://hdl.handle.net/10355/45673)

Lathan, S. R. (2023). A history of jogging and running—the boom of the 1970s. *Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center), 36*(6), 775–777. [https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2023.2256058](https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2023.2256058)

Li, B., Scott, O. K. M., & Dittmore, S. W. (2018). Twitter and Olympics. *International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 19*(4), 370–383. [https://doi.org/10.1108/ijsms-04-2017-0030](https://doi.org/10.1108/ijsms-04-2017-0030)

Lohn, J. (2025, June 23). The Sydney six: A group of teenagers launched a special era for USAswimming. Swimming World.[https://www.swimmingworldmagazine.com/news/the-sydney-six-a-group-of-teenagers-launched-a-special-era-for-usa-swimming/](https://www.swimmingworldmagazine.com/news/the-sydney-six-a-group-of-teenagers-launched-a-special-era-for-usa-swimming/)

lund0982. (2015). An introduction to running. One Foot in Front of the Other; Pressbooks.[https://pressbooks.umn.edu/running/chapter/chapter-1/](https://pressbooks.umn.edu/running/chapter/chapter-1/)

Mastromartino, B., Chou, W. W., & Zhang, J. J. (2017). The passion that unites us all: The culture and consumption of sport fans. In C. L. Wang (Ed.), *Exploring the rise of fandom in contemporary consumer culture* (pp. 52–70). IGI Global.

Media Culture. (2024, October 17). The psychology of fandom: What drives sports fans? | Media Culture. Mediaculture.com; Media Culture. [https://www.mediaculture.com/insights/the-psychology-of-fandom-what-drives-sports-fans](https://www.mediaculture.com/insights/the-psychology-of-fandom-what-drives-sports-fans)

Mering, A. (2016, July 25). Is a late U.S. Olympic trials a disadvantage? SwimSwam. [https://swimswam.com/late-u-s-olympic-trials-disadvantage/](https://swimswam.com/late-u-s-olympic-trials-disadvantage/)

Paris 2024 – Venues – Paris La Defense Arena. (2024). World Aquatics. [https://www.worldaquatics.com/competitions/paris-2024-venues-paris-la-defense-arena? utm](https://www.worldaquatics.com/competitions/paris-2024-venues-paris-la-defense-arena?utm)_

Pells, E. (2024, August 5). Olympic track’s best rivalry: 1,500-meter runners Kerr, Ingebrigtsen really do not like each other. AP News. [https://apnews.com/article/olympics-kerr-ingebrigtsen-rivalry-1317d90c1207c9f0a6d3a725e681d902](https://apnews.com/article/olympics-kerr-ingebrigtsen-rivalry-1317d90c1207c9f0a6d3a725e681d902)

Piercy, L., & Kiser, K. (2024, December 13). “Behind the blue”: The psychology behind sports rivalries, why we love to loathe the other team. UKNow. [https://uknow.uky.edu/research/behind-blue-psychology-behind-sports-rivalries-why-we-love-loathe-other-team](https://uknow.uky.edu/research/behind-blue-psychology-behind-sports-rivalries-why-we-love-loathe-other-team)

Post, J. J. (2024, August 11). How does Olympic swimming work? Events, schedule, scoring.ESPN.com; ESPN. [https://www.espn.com/olympics/story/_/id/40536738/olympic-swimming-events-rules-scoring](https://www.espn.com/olympics/story/_/id/40536738/olympic-swimming-events-rules-scoring)

Recreational running consumer research study Nielsen Sports. (2021). [https://assets.aws.worldathletics.org/document/60b741d388549ceda6759894.pdf?_gl=1](https://assets.aws.worldathletics.org/document/60b741d388549ceda6759894.pdf?_gl=1)

Rogers, C. (2018, June 29). Nike on how setting an “audacious goal” helped the brand work differently. Marketing Week. [https://www.marketingweek.com/nike-breaking2/](https://www.marketingweek.com/nike-breaking2/)

Rosado, L. (2024, July 5). 285,202 attendees across 17 sessions of U.S. Olympic swimming trials. SwimSwam. [https://swimswam.com/285202-attendees-across-17-sessions-of-u-s-olympic-swimming-trials/](https://swimswam.com/285202-attendees-across-17-sessions-of-u-s-olympic-swimming-trials/)

Ross, J. (2025, July 8). What happened to the international swimming league? Swimming World.[https://www.swimmingworldmagazine.com/news/what-happened-to-the-international-swimming-league/](https://www.swimmingworldmagazine.com/news/what-happened-to-the-international-swimming-league/)

Şarvan Cengiz, Ş., & Coşkun, E. Ş. (2023). Swimming in the Olympics. *International Journal of Sport Culture and Science, 11*(1), 56–70.

Schwarb, J. (2019, June 14). Pool of champions: IUPUI has been home to an aquatic jewel since 1982. News at IU.[https://news.iu.edu/stories/features/natatorium/history-aquatic-jewel-1982-national-sports-festival-olympics-louganis-meagher-phelps.html?utm](https://news.iu.edu/stories/features/natatorium/history-aquatic-jewel-1982-national-sports-festival-olympics-louganis-meagher-phelps.html?utm)_

Sears, E. (2015). Running Through the Ages, 2d Ed.. United States: McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers.

Shain, H. (2023, May 23). The power of sports storytelling: Not only driving more fans, but also more media value. Relometrics.com; Relo Metrics. [https://blog.relometrics.com/the-power-of-sports-storytelling-not-only-driving-more-fans-but-also-more-media-value](https://blog.relometrics.com/the-power-of-sports-storytelling-not-only-driving-more-fans-but-also-more-media-value)

Sim, J. (2025, March 31). Diamond league “welcomes” competition from Grand Slam Track as more broadcasters sign up. SportsPro.[https://www.sportspro.com/news/diamond-league-grand-slam-track-scheduling-broadcast-partners-march-2025/](https://www.sportspro.com/news/diamond-league-grand-slam-track-scheduling-broadcast-partners-march-2025/)

Takata, D. (2024, January 8). A brief history of women’s participation in Olympic swimming. SwimSwam. [https://swimswam.com/a-brief-history-of-womens-participation-in-olympic-swimming/](https://swimswam.com/a-brief-history-of-womens-participation-in-olympic-swimming/)

The Definitive Guide to Open Water Swimming. (2025). Usms.org. [https://www.usms.org/fitness-and-training/guides/open-water-swimming-101](https://www.usms.org/fitness-and-training/guides/open-water-swimming-101)

The history of Olympic swimming. (2018, December 17). Olympics.com; International Olympic Committee. [https://www.olympics.com/en/news/the-history-of-olympic-swimming](https://www.olympics.com/en/news/the-history-of-olympic-swimming)

Track & Field Ratings. (2024, May 5). Ustvdb.com. [https://ustvdb.com/networks/cnbc/shows/track-field/](https://ustvdb.com/networks/cnbc/shows/track-field/)

Vasile, L., Laurențiu Ticală, Rădulescu, A., Mujea, A., Matei, C., Braneț, C., Onoiu, C., Gheorghe, N., & Bălan, V . (2023). A ludic history of swimming: A systematic review. *Discobolul, 62*(2), 189–207. [https://doi.org/10.35189/dpeskj.2023.62.2.7](https://doi.org/10.35189/dpeskj.2023.62.2.7)

Vescio, J., Wilde, K., & Crosswhite, J. J. (2005). Profiling sport role models to enhance initiatives for adolescent girls in physical education and sport. *European Physical Education Review, 11*(2), 153–170. [https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336×05052894](https://doi.org/10.1177/1356336×05052894)

Vukovic, R. (2021, July 17). Tokyo games: Do the Olympics inspire us to be more active? Teacher Magazine. [https://www.teachermagazine.com/au_en/articles/tokyo-games-do-the-olympics-inspire-us-to-be-more-active](https://www.teachermagazine.com/au_en/articles/tokyo-games-do-the-olympics-inspire-us-to-be-more-active)

Wang, C. L. (Ed.). (2020). *Handbook of research on the impact of fandom in society and consumerism*. IGI Global. [https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-1048-3](https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-1048-3)

Wang, Z., Wang, Y . T., Gao, W., & Zhong, Y . (2023). Effects of tapering on performance in endurance athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. *PLOS ONE, 18*(5), e0282838. [https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282838](https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0282 838)

Welcome to the ancient Olympic Games. (2025). Olympics.com. [https://www.olympics.com/ioc/ancient-olympic-games](https://www.olympics.com/ioc/ancient-olympic-games)

YouTube. (n.d.). [Video].[https://youtu.be/hGleeVGS8F8?si=gszKPk5Cvu8v8JSW](https://youtu.be/hGleeVGS8F8?si=gszKPk5Cvu8v8JSW)

About the author

Kyle Padilla

Kyle is a high school senior with academic interests in history and environmental science. He has conducted research on the relationship between urban green space and biodiversity in U.S. cities. Outside the classroom, he is an avid athlete, competing year-round in swimming, cross country, and track, and he is especially interested in the role of sports beyond the Olympic stage.