Author: Aashi Agarwal

Mentor: Dr. Vivek Singh

Palo Alto High School

Abstract

According to the CDC, one in four adults in the United States has some type of disability. When government websites are not accessible, they effectively exclude millions of citizens from essential public services and perpetuate systemic barriers to information and participation. This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the digital accessibility of all 50 U.S. State Department of Transportation websites, employing a mixed-methods approach that integrates automated auditing with qualitative design analysis. Leveraging the Skynet Technologies Free Accessibility Checker, we gathered quantitative data on compliance with WCAG 2.2 standards, including compliance percentages (e.g. Ohio at 94.8%, Kansas at 14.7%), the total number of failed checks (e.g. ranging from 7 to 33), and the most commonly affected disability categories such as visually impaired users, people with cognitive or learning abilities, and users with dyslexia or color blindness. Qualitative analysis captured recurring usability issues such as semi-transparent image overlays, outdated web interfaces and a disconnect between stated ADA compliance and actual user experience. The results reveal wide disparities in accessibility performance across states and highlight the limitations of treating accessibility as a technical checkbox rather than a design imperative. Our findings call for a shift toward inclusive, user-centered practices in public digital infrastructure, where accessibility is embedded from the beginning and aligned with both legal mandates and civic responsibility.

Background

Web accessibility is the inclusive practice of designing digital platforms so that people with a wide range of disabilities, including visual, auditory, motor, or cognitive can perceive, navigate, and interact with content effectively. This includes accommodations for users who rely on screen readers, keyboard navigation, alternative text on images, and high-contrast visual design. Accessibility is particularly important for public sector websites, where equitable digital access can directly impact people’s ability to obtain critical services. Among these platforms, State Departments of Transportation, like state-level government agencies responsible for planning and coordinating federal transportation projects which set safety regulations for all major modes of transportation (USAgov, 2019): host websites that are frequently used by millions of people to get driver’s license-related information, job listings, construction alerts, weather-related road closures, and more. When addressing accessibility it is important to note that more than 1 in 4 adults in the United States has some type of disability (CDC, 2020). When these websites are inaccessible, they exclude citizens from critical public services and reinforce systemic barriers to information.

The central problem is that despite legal and technical standards, accessible information across State Departments of Transportation websites remains inconsistent and insufficient. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)– i.e., a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in many areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and many public and private places that are open to the general public (ADA National Network)–applies to digital services offered by state agencies. While the ADA establishes the legal foundation for accessibility, it does not specify technical requirements for digital content. That role is filled by the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), developed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) to ensure content is perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust. The latest version, WCAG 2.2, outlines criteria such as color contrast, keyboard navigation, and logical heading structures (W3C, 2019). Although not law, WCAG is widely recognized as the standard for evaluating ADA compliance in audits and court cases (Gibson, 2024).

Ensuring accessibility is not just a matter of legal compliance, but also of public equity, civil participation, and good digital governance. As the U.S population ages and more individuals identify as having disabilities, the need for inclusive design becomes increasingly urgent. Accessible design– i.e., the practice of designing products, services, and environments that can be accessed, understood, and used by all individuals (Accessibility in Design – Definition and Explanation, 2024) also improves overall usability for people without disabilities such as people using mobile devices or unfamiliar platforms. When public agencies fail to prioritize accessibility, they risk excluding large segments of the population from essential services and commutation. This not only violates the spirit of ADA but also undermines the effectiveness of digital government.

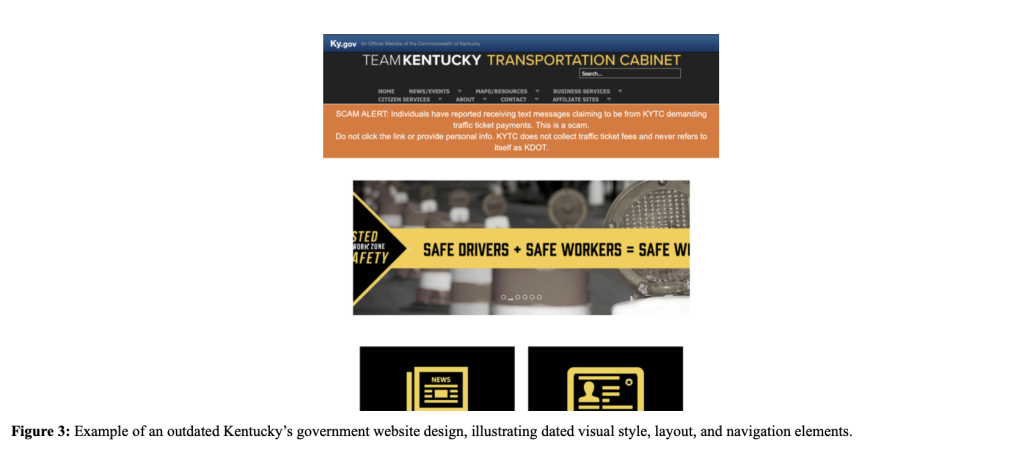

To investigate these issues, we conducted a mixed-methods evaluation of all 50 U.S State Department of Transportation websites. Based on our data we identified several recurring qualitative trends: many sites made frequent use of semi-transparent images that interfere with text readability, almost all websites included ADA documentation but failed to follow through with the actual implementation, and a significant number of sites exhibited a retro web design–i.e., style incorporating visual, typographic, and layout elements from past decades like bold color palettes, pixel-style graphics, retro fonts, and aesthetics nods to web design from the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s (Seattle SEO Company, 2022). In parallel, we also captured compliance percentage, and the most commonly affected disability categories like visually impaired users, people with cognitive or learning abilities, and users with dyslexia or color blindness. These findings reveal that technical compliance and user-centered design often diverge, and that while some states show strong adherence to WCAG standards, others fall short due to overlooked accessibility principles.

Related Work

Research on digital accessibility in public-sector services has revealed widespread noncompliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, especially on state-run websites. For example, Jaeger argues although the ADA legally guarantees equal access to public services, its digital enforcement remains weak, leading to systemic exclusion for people with disabilities, especially on platforms operated by state and local governments (Olalere & Lazar, 2011). Goode builds on this by examining how Title II of the ADA, which applies to public entities, often lacks enforceability when applied to web infrastructure, leaving many agencies noncompliant without legal consequence (Goode, 2021). These studies provide critical legal and infrastructural context, but stop short of assessing individual domains, such as transportation agencies. They emphasize the existence of a digital divide not only due to technology access, but due to suboptimal design decisions that fail to meet technical accessibility benchmarks like those defined in WCAG 2.2.

In parallel, the importance of website aesthetics and structure in shaping usability has been explored through design-focused studies of government web portals. Watkins and Wills, for instance, analyze the digital design of U.S. city government websites and describe a recurring “legacy design trap”, in which outdated layouts, unresponsive interfaces, and poor information hierarchy diminish the user experience, particularly for underrepresented and aging populations (Wagner et al., 2024). In the transportation sector, Graham Currie and Mandy Gook conduct usability testing on a sample of transportation agency websites, identifying serious issues in visual consistency, navigation, and user trust. Their work supports the idea that design shortcomings are not purely aesthetic but functionally consequential in reducing civic engagement (Currie & Gook, 2009). Similarly, Patricia Acosta-Vargas applied automated tools to evaluate a set of business websites for accessibility metrics, providing a technical foundation for large-scale digital evaluations (Acosta-Vargas et al., 2017). Unlike these studies, which focus on localized or small-scale usability assessments, my analysis interrogates accessibility as both a design and equity issue, examining how aesthetic and structural flaws intersect with legal compliance gaps. This approach moves beyond surface-level usability to reveal how design decisions can perpetuate systemic exclusion within essential public infrastructure.

A clear gap remains in applying accessibility research insights to a comprehensive, cross-state assessment of Department of Transportation websites. This study addresses that gap by conducting a dual-pronged evaluation of all 50 U.S. State Department of Transportation websites, an especially critical domain given that these agencies serve as gateways to essential public services such as road safety updates, construction notices, licensing, public transit schedules, and emergency evacuation information. When these sites are inaccessible, individuals with disabilities face disproportionate barriers to mobility, safety, and civic participation. Guided by the question of to what extent these websites comply with WCAG 2.2 accessibility standards and how design choices affect their usability and inclusivity for people with disabilities, we pairautomated quantitative auditing with qualitative observations. By bridging legal, technical, and experiential dimensions, our research uniquely situates itself within and beyond existing literature, offering a holistic, data-informed snapshot of how Department of Transportation websites across the U.S. comply with the standards of digital accessibility and modern design in 2025.

Methods

This study employed a mixed-methods approach to evaluate the accessibility of all 50 U.S. State Department of Transportation websites. The URLs for each website were obtained from the Federal Highway Administration’s directory (U.S. Department of Transportation, 2019) to ensure official and consistent sources across all states. Before conducting the full audit, three web accessibility tools, Skynet Technologies Free Accessibility Checker, AccessibilityChecker.org, and AEL Accessibility Checker, were pilot tested to determine the most comprehensive and reliable platform. The Skynet tool was ultimately selected for its detailed reporting capabilities, which include overall compliance percentages, issue categories (for example, clickables, tables, audio/video), WCAG 2.1 conformance levels (A, AA, AAA), and mapped locations of accessibility violations within the HTML structure. Although the tool required more manual time per page and lacked fine-grained disability categorization, it provided the most consistent and unrestricted data collection without login barriers or scan limits.

Because Department of Transportation websites are large and highly variable, only two pages per site were selected for auditing: the homepage and the first critical navigation page. This decision balanced cross-state comparability with practical feasibility while still capturing the sections most frequently used by the public. The homepage was selected as the most common entry point for both general and assistive-technology users, while the first critical navigation page represented the site’s most essential public task. To avoid arbitrary selection, a standardized decision rule was applied: beginning from the homepage’s global navigation bar, the first listed link that matched one of the following categories, Driver Services or Licensing, Road Conditions or Closures, Jobs or Careers, Transit Schedules or Permits, was chosen. If multiple categories appeared, “Driver Services/Licensing” was prioritized due to its broad public relevance. When a navigation menu lacked those options, the first link leading to a transactional or informational task page (rather than a press release or PDF list) was selected. This consistent process ensured methodological transparency and reproducibility. While auditing only two pages limits the comprehensiveness of within-site analysis, it allowed for a uniform evaluation across all fifty states and captured the design and accessibility conditions most visible to users.

Each selected page was scanned using the Skynet checker, and the resulting data were recorded for each state, including the percentage of accessibility checks passed, total number of failed checks, categories of issues, corresponding WCAG conformance levels, and affected disability types. A subset of flagged items, particularly color contrast and missing form labels, was manually verified through HTML inspection to validate the tool’s accuracy. Beyond automated results, qualitative observations were added to capture design elements not detected by scanning software, such as semi-transparent overlays, poor visual hierarchy, and mismatched ADA statements. To analyze these qualitative features systematically, an a priori codebook was developed around recurring design themes such as legibility, information structure, and visual clutter. Two independent coders applied the codebook to a stratified 20 percent sample of websites selected across high, medium, and low compliance categories. Inter-rater reliability was calculated using Cohen’s kappa, with a target threshold of 0.75 for substantial agreement. Discrepancies were resolved collaboratively, and the finalized codebook was applied to the remaining sites by the primary coder with periodic spot checks to prevent drift.

To strengthen internal validity, a post hoc subset of ten websites underwent manual WCAG checklist testing focused on success criteria most frequently implicated in the automated findings, including 1.4.3 (Contrast), 1.3.1 (Info and Relationships), and 2.1.1 (Keyboard Navigation) (W3C, 2024). These manual checks were paired with basic task-based tests, such as locating renewal information or road closures using keyboard-only navigation, to evaluate whether the issues flagged by automation corresponded to tangible usability barriers.

Several limitations accompany this methodology. First, analyzing only two pages per website constrains the ability to generalize findings across entire sites. The decision to do so reflects a necessary balance between breadth, covering all fifty states, and depth, though future research should expand to include deeper navigational flows and internal task pages. Second, automated tools typically detect only 30 to 40 percent of accessibility violations, as many issues, such as reading order, focus visibility, and contextual link meaning, require human interpretation. Although manual validation and qualitative review were used to mitigate this limitation, undetected errors may remain. Third, while inter-rater reliability was established on a subset of sites, qualitative interpretation beyond that sample may still contain subjectivity. Additionally, because Department of Transportation websites frequently update banners, alerts, and layouts, the results represent a snapshot of accessibility performance at a single point in time. Lastly, the findings are partially shaped by Skynet’s proprietary detection algorithms, meaning results could vary with alternative auditing platforms. Despite these constraints, the combined quantitative and qualitative approach offers a robust, reproducible framework for assessing both technical accessibility and user-centered design quality across large-scale public web infrastructure.

Results

One of the most revealing findings in our audit was the wide variation in accessibility compliance across the 50 U.S. State Department of Transportation websites. Overall compliance scores ranged from 14.7 percent (Kansas) to 94.8 percent (Ohio), with a mean of 68.9 percent, a median of 70.4 percent, and a standard deviation of 16.2. This range indicates substantial disparity in digital accessibility across states. While a small subset of websites exceeded 90percent compliance, suggesting strong alignment with WCAG 2.2 standards, nearly half of the states fell below 70 percent, placing them in the semi-compliant or noncompliant category. These findings underscore that accessibility is not being uniformly prioritized, even though these websites serve as primary entry points to essential public services.

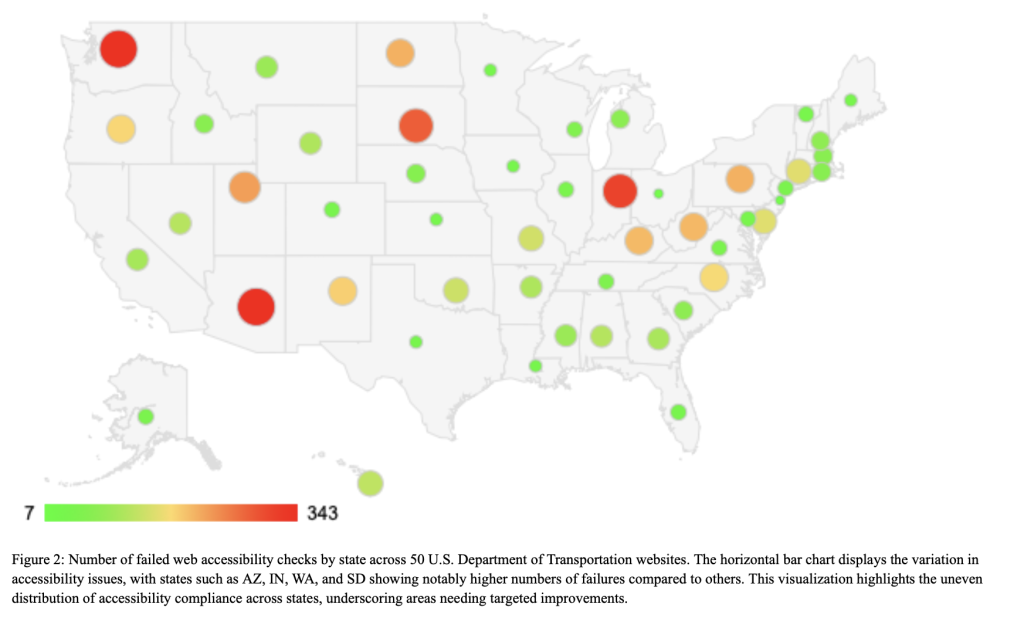

In tandem with compliance percentages, the total number of failed checks per site provided further insight into accessibility gaps. Across all 50 websites, the number of failures ranged from 7 to 33, with a mean of 18.5, a median of 17, and a standard deviation of 6.3. A Pearson correlation analysis between the compliance percentage and number of failed checks revealed a strong negative relationship (r = –0.87), indicating that lower compliance percentages were closely associated with higher counts of accessibility violations. This confirms that automated scoring aligned with practical accessibility performance: as the number of failures increased, overall compliance predictably declined.

Across all sites, the most frequent accessibility failures involved poor color contrast, unlabeled form elements, missing alternative text, and improperly structured headings. Color contrast errors were the single most common issue, appearing on 88 percent of audited pages. These problems most directly affect users with visual impairments, who comprised the most impacted disability category according to tool classification data. Users with mobility impairments were also frequently affected, particularly when keyboard-only navigation failed or focus indicators were missing from interactive elements. Cognitive accessibility issues appeared less frequently, though dense text structures and inconsistent navigation patterns created additional barriers for some users.

Qualitative analysis reinforced these quantitative findings. One of the most pervasive design flaws observed was the use of semi-transparent images layered behind text or interactive elements. Over half of the websites used banners or background visuals that reduced text readability, particularly in combination with low-contrast color palettes. While intended to enhance visual appeal, these choices often compromised functional accessibility for users with low vision or reading impairments. This tension between aesthetic branding and practical usability reflects a broader misalignment between design intent and user inclusion.

A second major qualitative issue involved ADA compliance statements. Nearly all websites included a footer or dedicated page declaring adherence to the Americans with Disabilities Actor referencing WCAG standards. However, in many cases, these declarations did not correspond with actual usability. Unlabeled navigation links, inaccessible PDFs, and missing screen reader compatibility persisted despite such statements. This disconnect suggests that accessibility is too often treated as a formal requirement rather than an integrated design value.

Lastly, a large proportion of websites displayed visually and structurally outdated layouts, characterized by retro web design features such as bold color palettes, dense typography, pixel-style graphics, and nonresponsive navigation. These stylistic elements, reminiscent of early 2000s web design, were common among low-performing states and corresponded with lower compliance scores. Although such designs do not directly violate WCAG standards, they undermine usability by reducing clarity, scalability, and modern functionality. The persistence of these outdated designs indicates a lack of investment in modernization and highlights how institutional neglect can perpetuate digital inequity.

Taken together, these quantitative and qualitative results suggest that accessibility performance across U.S. State Department of Transportation websites varies widely and follows clear patterns. The strong negative relationship between compliance scores and failure counts reinforces that many accessibility problems are structural rather than incidental. The recurring qualitative trends, visual obstruction, performative ADA compliance, and outdated design, further reveal that technical adherence alone is insufficient. Accessibility, when treated as a checklist rather than a design ethic, continues to fall short of ensuring equitable digital access.

Discussion

The results of this study highlight that digital accessibility must be treated as a core design priority rather than an afterthought. One of the most revealing findings was the percentage of accessibility checks passed across the 50 U.S. State Department of Transportation websites, which provided a general benchmark of compliance with WCAG 2.2 standards. While a handful of states achieved high compliance (above 90%), a significant portion scored well below that, often in the 60–70% range, placing them in the semi-compliant category, and a few even dipped below 50%, indicating a severe lack of attention to accessibility.

This inconsistency underscores that accessibility is not being uniformly prioritized, even though these websites serve as primary entry points to essential public services. While automated tools can flag compliance issues, many of the most disruptive problems, like our qualitative issues, stem from broader design decisions that prioritize aesthetics or legacy structures over usability. This suggests that accessibility must be embedded into the design process from the beginning, with thoughtful attention to how content is visually presented, navigated, and interacted with across diverse user needs. Designers and developers should move beyond minimal compliance and adopt inclusive design practices that address both technical standards and real-world user experiences.

The findings also connect to broader discussions of digital inequality. Accessibility gaps on government websites do not merely represent technical oversights; they reinforce existing disparities in civic participation, mobility, and access to information. When people with disabilities cannot easily navigate transportation websites, they face compounded barriers to employment, healthcare, and education. These inequities mirror a larger pattern in digital governance where technological design choices can either expand or restrict public inclusion. Addressing accessibility, therefore, is not only about fixing websites but about ensuring that digital infrastructure functions as a public good that serves all users equitably.

Moreover, the gap between stated ADA compliance and actual usability points to the need for more transparent, user centered workflows in public sector web development. Merely posting accessibility statements does little if sites remain functionally inaccessible. Agencies should incorporate routine manual audits, iterative usability testing with individuals with disabilities, and continuous training for design teams to better understand accessibility beyond code-level fixes. This also calls for inter-agency collaboration and standardization efforts that can ensure consistency across states, reducing the accessibility divide.

From a policy perspective, these findings suggest several actionable steps. State and federal agencies should establish standardized accessibility benchmarks for all government websites, accompanied by annual reporting and public accountability mechanisms. Accessibility audits should be integrated into procurement and design contracts, ensuring compliance from the earliest stages of development. Federal oversight could also incentivize interagency collaboration through shared design systems and centralized accessibility resources, reducing redundancy and improving consistency across states. Finally, accessibility should be framed not just as a compliance goal but as a measure of digital equity, directly tied to broader civil rights objectives and inclusive governance.

Ultimately, digital accessibility should be treated not only as a legal and technical requirement but as a moral and civic responsibility, essential to building equitable public services. By viewing accessibility through the lens of digital inequality and embedding it within public policy and design practice, governments can move closer to realizing the promise of technology as a tool for inclusion rather than exclusion.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reveals that while some U.S state Department of Transportation websites demonstrate meaningful progress toward digital accessibility, the majority fall short of providing equitable, user-centered online experiences for people with disabilities. Through both quantitative data and qualitative observations, we found a persistent disconnect between stated ADA compliance and actual usability, with recurring issues that disproportionately affect users with visual, mobility, and cognitive impairments. These findings underscore the need for accessibility to be fully integrated into the design and development lifecycle of public websites as a foundational principle of inclusive governance. As digital access becomes increasingly central to civic participation and public service delivery, state agencies must recognize accessibility as both a civil rights imperative and a design obligation in order to ensure that all citizens can navigate, interact with, and benefit from digital infrastructure that supports everyday life.

Bibliography

Accessibility in Design – Definition and Explanation. (2024, June 10). The Oxford Review – or Briefings. https://oxford-review.com/the-oxford-review-dei-diversity-equity-and-inclusion-dictionary/accessibility-in-design-definition-and-explanation/

Acosta-Vargas, P., Lujan-Mora, S., & Salvador-Ullauri, L. (2017). Quality evaluation of government websites. 2017 Fourth International Conference on EDemocracy & EGovernment (ICEDEG). https://doi.org/10.1109/icedeg.2017.7962507

ADA National Network. (n.d.). What is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)? ADA National Network. https://adata.org/learn-about-ada

CDC. (2020). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CDC. https://www.cdc.gov

Currie, G., & Gook, M. (2009). Measuring the Performance of Transit Passenger Information Websites. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2110(1), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.3141/2110-17

Gibson, D. (2024, November 8). 2024 WCAG & ADA Website Compliance Requirements | Accessibility.Works. Accessibility.works. https://www.accessibility.works/blog/2025-wcag-ada-website-compliance-standards-requirements/

Goode, L. F. (2021, March 8). About | HeinOnline. HeinOnline. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/hlelj38&div=8&id=&page=.

Olalere, A., & Lazar, J. (2011). Accessibility of U.S. federal government home pages: Section 508 compliance and site accessibility statements. Government Information Quarterly, 28(3), 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2011.02.002

Seattle SEO Company. (2022, April 16). Retro Web Design. Seattle Web Design & SEO Agency; Seattle Web Design Agency. https://visualwebz.com/retro-web-design/

US Department of Transportation. (2019). State Transportation Web Sites | Federal Highway Administration. Dot.gov. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/about/webstate.cfm

USAgov. (2019). Official Guide to Government Information and Services | USAGov. Usa.gov. https://www.usa.gov

W3C. (2019). World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). W3.org. https://www.w3.org

W3C. (2024, December 12). Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) Overview. Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI). https://www.w3.org/WAI/standards-guidelines/wcag/

Wagner, M., Manish Shirgaokar, Misra, A., & Marshall, W. (2024). Navigating ADA Compliance. Journal of the American Planning Association, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2024.2343661

About the author

Aashi Agarwal

Aashi Agarwal is a designer, accessibility advocate, and creative leader passionate about the intersection of technology, communication, and inclusion. She specializes in human-centered design and digital accessibility, developing tools and platforms that make information and interaction more equitable. Her work with organizations such as the NIMBLE Mindset has focused on translating complex data into intuitive, interactive storytelling that highlights impact and community. Aashi also explores how inclusive design principles can extend beyond digital interfaces into cultural and artistic spaces.

In her leadership role within the performing arts community, she has spearheaded initiatives to expand access to live theatre, including implementing ASL interpretation and inclusive audience design practices for school productions, and developing programs that welcome and support diverse participants. She aims to continue bridging the gap between structure and creativity to design systems that empower diverse voices and create meaningful, accessible experiences for all users.