Author: Vishal Ramamurthy

Mentor: Dr. Waheed U. Bajwa

Carlmont High School

Abstract

Integrated circuits, familiarly known as chips, have tremendous applications in modern society within several fields such as medicine, entertainment, and computer engineering. These chips’ layout and design are crucial toward their overall functionality, efficiency, and power consumption, and are constantly being changed to achieve the highest possible level of results. Existing methods, such as modular placement using quadratic or clustering techniques, have been able to achieve moderate to high levels of efficiency. However, these methods face challenges in comprehensively accounting for all factors that contribute to improved chip performance. Recently, the method of using reinforcement learning for the placement of modules within chips has been explored and discussed by researchers as a viable technique for ideal placement. The purpose of this paper is to discuss the previous methodologies of improving module placement and comparing these methods to the usage of reinforcement learning within this problem domain; furthermore, this paper also explores the possible benefits and detriments of reinforcement learning, as well as its implications for future usage within this domain. This literature review observes that reinforcement learning methods for placement demonstrate improvements in wirelength but require refinement in the context of meeting design constraints and requirements.

I. Introduction

Integrated circuits are small units created from precise connections between electronic components (Pan, 2023), such as resistors and transistors, that are typically built on a silicon (Si) substrate; integrated circuits are physically manufactured using photolithography – using ultraviolet (UV) light to place thousands of components onto the substrate at once (Saint & Saint, 2018). These chips are initially designed through a meticulous process with several components, including logic design, where the necessary functionality of it is defined through logic simulations, and physical design, where important functions and the input and output ports of the circuit are defined (Synopsys, n.d.). The flow of the design process includes the stages in the front-end, like design and logic synthesis, followed by back-end processes such as placement and routing (Cadence 2023). Each of these phases within the design process must balance performance, power, and area availability (PPA) metrics under nanometer-scale constraints. Many modern algorithms are made to prefer one of these three PPA metrics specifically; as will be discussed later, reinforcement learning can try to consider all three factors to create the best possible output.

Within this design process, module placement emerges as the central challenge for PPA optimization that influences signal delay, routing congestion, and overall power consumption. The performance of these circuits heavily relies on integration density and signal congestion, both factors which hinge on the effective placement of modules within the integrated circuit. As the geometries of devices shrink over time, improved module placement becomes a bigger priority, which dictates the physical proximity of high-interaction blocks and ultimately chip yield.

II. Background on Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning is a machine learning technique that involves an algorithm, as a result of learning through continuous interactions with its environment (Kumar Shakya, Pillai, & Chakrabarty, 2023), creating an optimal behavioral strategy (known as a policy) based on reward signals given from the interactions. Rewards are mostly dense, meaning feedback is given often; partial, meaning that the signal is given in intermediate steps before the goal; or sparse, which only provides rewards for specific goals. The policy tells the reinforcement learning agent, or entity that is trying to learn the specific task, how to act for any given state – the situation or outline the agent is placed in. Reinforcement learning is sequential-based (Kumar Shakya, Pillai, & Chakrabarty, 2023), meaning that the reinforcement learning agent makes decisions over time where each action taken by the agent affects the next state and the overall outcome. The overall benefits and detriments of each state and action are evaluated using value functions — specifically, the State-Value Function and the Action-Value Function (Hardik, 2025).

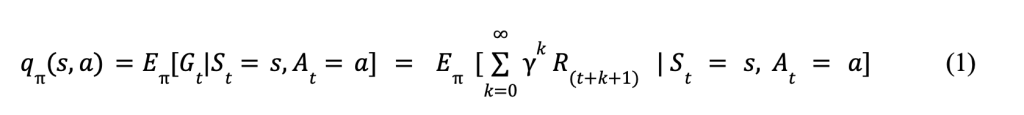

Shown in (1) is the Action-Value Function which determines how beneficial or detrimental an action was based on the policy (π). The function returns an expected value from an action (a) upon an initial state (s). St and At represent the state of the environment and action taken at time t (Hardik, 2025)

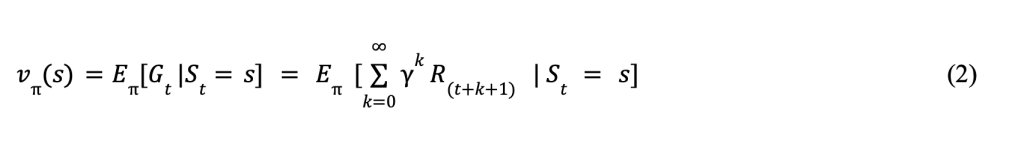

displays the State-Value Function, which determines how optimal a state is when following the policy denoted by π . It returns an expected value given the state (s) and the following policy acted upon the state. Here, St is the current state at time t similar to (1) (Hardik, 2025).

In both equations, Eπ represents the expectation over all future sequences in combination Gt which is the total discounted reward starting at a time (t). The summation from k=0 to infinity ![]() is the infinite sum over all of the future possible rewards, and this summation is taken into account with the discount factor yk comparing future to immediate rewards as well as the reward (R(t+k+1)) received k+1 steps after the current state.

is the infinite sum over all of the future possible rewards, and this summation is taken into account with the discount factor yk comparing future to immediate rewards as well as the reward (R(t+k+1)) received k+1 steps after the current state.

The goal of a reinforcement learning algorithm is to find the most optimal policy possible to take the best action that maximizes positive rewards given any state within the system. Using equations such as the State and Action Value Functions guides the search for optimal policies through taking subsequent states and actions into consideration.

III. Methodology

To conduct research and analysis on how reinforcement learning and traditional methods can be applied to modular placement within integrated circuits, I performed a structured literature review and comparative analysis. The goal of using this methodology was to identify the traditional methods of modular placement, evaluate recent approaches for using reinforcement learning within the problem domain, and finally compare the classical methods with reinforcement learning based on PPA metrics. Some databases I searched to conduct this literature review included ArXiv, Google Scholar, and IEEE Xplore to find constructive, peer-reviewed papers on placement methods and reinforcement learning. To ensure relevance and quality, papers from these databases were selected using the following criteria: they presented a placement methodology which is applied to integrated circuit design, described measurable outcomes tied to PPA metrics, and introduced techniques within the methodology that apply to macro or global placement. The final stage of the methodology consisted of categorizing classical methods and reinforcement learning methods separately, identifying their strengths and areas for improvement, and summarizing emerging themes that motivate future research within this area.

IV. Traditional Placement Approaches

For refined placement and routing within an integrated circuit to maximize PPA, several methods have been taken to achieve the most efficient setup possible.

One of these is the methodology of using quadratic placement to minimize wirelengths by treating the modules within the integrated circuits as “springs.” For quadratic placement, a commonly used placement tool is GORDIAN (Kleinhans et al., 1991), which, using the calculated positions of the cells, places all modules concurrently during each partitioning stage. The loop within GORDIAN aims to achieve the smallest possible wirelength given the area constraints for placement. It achieves this result through, given an input of a netlist—a description of how electronic components connect within a circuit—, repetition of a loop until each partitioned region of the area is filled with a certain number of modules (Kleinhans et al., 1991). The decision on where to create partitions for GORDIAN comes from the calculated global placement of the modules, but these partitions can also be improved through constant verification of the partition decisions to get the most desired area ratio (Kleinhans et al., 1991). Quadratic methods, although efficiently optimizing wirelengths, face several limitations such as strict non-overlap guarantees and the neglect of congestion and routing.

Along with formulating the placement of modules as a quadratic placement problem, another method coupled with this is the integration of using clustering and unclustering (Nam et al., 2006) to reduce the scale of the problem while keeping the quality of the solution. A placement program called analytical top-down placement (ATP) has hierarchical clustering (Nam et al., 2006) — a method in machine learning that structures clusters of similar data points in a hierarchical manner — integrated with it which speeds up the global (all-encompassing) placement of modules within the integrated circuit and makes favorable performance tradeoffs in order to achieve minimal wirelength and effective handling of fixed blocks such as memory blocks. In comparison with normal ATP, there is a 2.1 times increase in runtime with an approximately 1.4% improvement in wirelength (Nam et al., 2006), proving that using hATP (hierarchical ATP) is a viable method for achieving mostly ideal results in regards to the task of module placement. On the other hand, the method of analytical bottom-up clustering, as opposed to ATP, needs to have an associated effective clustering function that achieves a targeted ratio for a clustered netlist as compared to the total modules in the original netlist (Nam et al., 2006), which means that the problem size of the netlist is essentially being reduced through clustering in a different manner than ATP but still works efficiently. Along with this challenge, the clustering methods must respect block constraints that are immovable to ensure that the clusters remain feasible, or achievable.

Modern designs are moving towards efficient 3D integration with modular placement in chips. Using 3D integration with mixed-sized modules (Zhao et al., 2025), such as large macros and standard cells, aims to satisfy interconnectivity and non-overlapping constraints. The framework of this methodology involves using a 3D global placement approach to explore the placement area provided for the shortest possible wirelengths; minimal wirelengths are achieved through macro-rotations in between global placements (Zhao et al., 2025). By doing this method, possibly limited solution quality, which is an effect of partitioning, is avoided; however, overlaps or infeasability still may occur, which requires a legalization (rule-validation) fix or discrete steps for correction.

As integrated circuit designs grow increasingly more complex, though, traditional placement methods’ common limitations motivate growth and exploration into using reinforcement learning for the placement of modules.

V. Applying Reinforcement Learning to Module Placement

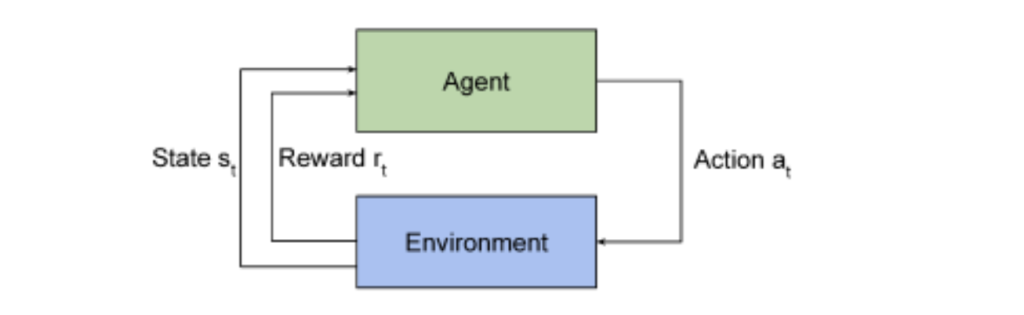

In recent years, reinforcement learning has emerged as a viable tool for improving the placement of modules within integrated circuits. The methodology of framing the modular placement problem as a reinforcement learning task makes the policy a deep neural network (Goldie & Mirhoseini, 2020) and expresses partial rewards from the given state-action function as a proxy-cost function—a blend of metrics such as wirelength, congestion, and density—which estimates the final power, performance, and area (PPA). Evaluating the full PPA metrics would be computationally prohibitive, so per training cycle, the reward function relies on an analytical cost estimator (Goldie & Mirhoseini, 2020) to see how much power, performance, and area the reinforcement learning agent is using. The training of the agent involves using policy-gradient reinforcement learning (Goldie & Mirhoseini, 2020): episodes, or complete sequences of an agent’s interactions in reinforcement learning, consist of sequential macro (larger-scale) placements until all blocks are positioned, and then each episode’s reward, derived from the placements’ congestion, wirelength, and density, is normalized and used to update the parametrized policy, a type of policy that is explicitly defined by a set of adjustable parameters (Goldie & Mirhoseini, 2020). The interactions between a reinforcement learning agent and its environment are demonstrated in Figure 1. This reinforcement learning usage allowed for near-optimal PPA to be achieved in a short amount of time, and the framework is very automated which reduces some need for legalization, which is a persisting issue with reinforcement learning algorithms. Similarly, traditional quadratic placement methods also require legalization, but reinforcement learning enables for faster convergence and more desirable results with not only improved wirelengths, but also reduced amounts of power usage.

Chip macro-module placement can also be done through hierarchical reinforcement learning (Tan & Mu, 2024) as opposed to deep reinforcement learning. A two-level policy approach is used for this method, where the high-level agent determines partitioning for the macros, which allows the lower-level agent’s policy to granularly place macros within the partitioned region of the total allocated area. By adopting Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning for Placement (HRLP), dense rewards are calculated for each episode by observing differences between congestion and wirelength to better all three metrics of PPA (Tan & Mu, 2024). The proposed model demonstrated improvements for Half-Perimeter Wire Length of 9.29% and 14.25% (Tan & Mu, 2024), which is extremely substantial; but, standard cell placement, in contrast with macros, still relies on traditional analytic tools and the initial partitioning of the entire placement region could restrict the reinforcement learning agent from discovering globally optimal modular placements.

Figure 1. A reinforcement learning agent interacts with its environment to achieve the best possible rewards based on the action taken and the state. (Goldie, A., & Mirhoseini, A. (2020))

Developing reinforcement learning methods for placement naturally create points of comparison with traditional methods to evaluate both the relative strengths and weaknesses of each technique.

1. Comparing Reinforcement Learning and Traditional Methods

Traditional methods and reinforcement learning have both proven to be viable methodologies of placing modules within integrated circuits. However, reinforcement learning has shown to have a greater impact in improving wirelengths within the circuit as compared to previous methods: a substantial 14.25% Half-Perimeter Wire Length (Tan & Mu, 2024) improvement from HRLP as compared to hATP’s 1.4% (Nam et al., 2006) wirelength improvement demonstrates a greater benefit for the PPA metrics of area and performance through improving chip compactability and operating frequency. Additionally, reinforcement learning has potential for faster algorithms with the usage of neural networks, but these can be computationally expensive to train as compared to methods such as quadratic placement. Reinforcement learning also has a more demanding need for legalization as compared to classical methods due to the increased potential for the algorithms to not adhere to all of the design constraints, possibly causing modules to overlap, leading to short circuiting. Overall, reinforcement learning’s demonstrated benefits but possibly detrimental costs can greatly impact whether classical methodologies will continue to be widely used for modular placement within integrated circuits. An overview of the different methods’ strengths and limitations is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1 Comparison Table of Placement Methods

| Method Name | Wirelength Improvement | Key Strength | Main Limitation |

| GORDIAN (Quadratic Placement) | Minimal to moderate improvement | Uses quadratic modeling to effectively minimize global wirelengths | Does not explicitly account for congestion |

| hATP (Hierarchical Analytical Top-Down Placement) | Around a 1.4% wirelength improvement (Nam et al., 2006) | Hierarchical clustering improves the speed of global module placement | The clustering decisions must explicitly meet the block constraints |

| 3-D Placement | 3D macro rotation and global exploration indirectly improve wirelengths slightly | Partitioning-related quality loss is reduced and modern 3D chip layouts are supported | May create overlaps, so it requires some post-processing legalization |

| HRLP (Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning for Placement) | 9.29%–14.25% improvement in wirelength (Tan & Mu, 2024) | Wirelength improvements are significant given that density and congestion are both considered | There are high computational costs and due to initial partitioning limits, global improvements could be slightly restricted |

Note. All values and descriptions displayed in this table are drawn directly from the information on the placement methods discussed in the preceding sections.

While this comparison between the traditional and reinforcement learning approaches for module placement highlights clear trends across the methods, it also reveals challenges and openings for improvement that shape the limitations of the current research landscape.

VI. Limitations

Although this review produces a comparative analysis of traditional integrated circuit module placement approaches and reinforcement learning-based techniques, some limitations exist that constrain the scope of the findings. As a part of this literature review, some traditional methods, such as simulated annealing-based placement and force-directed placement, were not covered because of their similar usages and functions within integrated circuit module placement to popular methods like quadratic placement and hierarchical placement. Some earlier placement methods were also not included due to their limited public availability, and detailed placement as a whole is not fully addressed in this review. Finally, reinforcement learning research on integrated circuits remains a developing field in which the experimental techniques are not evaluated on consistently benchmarked circuits; this fact limits some direct comparison between methods across extensive studies. Recognizing these discussed limitations helps clarify how results of the study should be interpreted and sets the stage for outlining the broader implications and future outlook within this problem domain.

VII. Conclusions

Modular placement within integrated circuits can be optimized through a variety of methods, with each method having its own constraints, uniqueness, and priorities for efficiency. Modern algorithms have proven to be useful in achieving consistently moderate to high efficiencies, but they are limited in the sense that some PPA metrics typically must be prioritized over the others. Reinforcement learning has its benefits of trying to optimize all factors within PPA through a sequential-based learning process, but can also come with detriments such as the need to legalize certain actions to limit structural damage, the need for scalability and the unpredictability of actions. As a result, legalization of reinforcement learning algorithms should move toward being reduced overhead by using predictive filters or developing constraints.

Additionally, reinforcement learning should be tested on standardized benchmark circuits initially to evaluate the performance of the algorithm separately on macro-heavy and standard cell-heavy designs. Considering that there are various factors to account for within the problem domain, future studies should explore specific applications of reinforcement learning — such as with single-factor reward functions or with graph neural networks for improved netlist connectivity — on one PPA factor at a time so that we can further our knowledge on how to best optimize modular placement, which will lead to improved signal integrity, lower power dissipation, and an overall more efficient chip performance.

VIII. Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Waheed U. Bajwa for his mentorship and guidance in my research, as well as reviewing and helping to edit this paper.

References

Pan, Y . (2023). Typical Application Circuit Analysis of Digital Integrated Circuits in Electronic Devices. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Technologies and Electrical Engineering, 60–64. https://doi.org/10.1145/3640115.3640125

Saint, C., & Saint, J. L. (2018). integrated circuit | Types, Uses, & Function. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/technology/integrated-circuit IC Design and Manufacturing Process. (2023, August 2). Resources.pcb.cadence.com. https://resources.pcb.cadence.com/blog/2023-ic-design-and-manufacturing-process

What is Integrated Circuit (IC) Design? – How Does it Work? | Synopsys. (n.d.). Www.synopsys.com. https://www.synopsys.com/glossary/what-is-ic-design.html

Kumar Shakya, A., Pillai, G., & Chakrabarty, S. (2023). Reinforcement Learning Algorithms: A brief survey. Expert Systems with Applications, 231, 120495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120495

Dave, H. (2021, February 13). Bellman Optimality Equation in Reinforcement Learning. Analytics Vidhya. https://www.analyticsvidhya.com/blog/2021/02/understanding-the-bellman-optimality-eq uation-in-reinforcement-learning/

Kleinhans, J. M., Sigl, G., Johannes, F., & Antreich, K. (1991). GORDIAN: VLSI placement by quadratic programming and slicing optimization. 10(3), 356–365. https://doi.org/10.1109/43.67789

Nam, G.-J., Reda, S., Alpert, C. J., Villarrubia, P. G., & Kahng, A. B. (2006). A fast hierarchical quadratic placement algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, 25(4), 678–691. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcad.2006.870079

Zhao, Y ., Liao, P., Liu, S., Jiang, J., Lin, Y ., & Yu, B. (2025). Analytical Heterogeneous Die-to-Die 3-D Placement With Macros. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, 44(2), 402–415. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcad.2024.3444716

Goldie, A., & Mirhoseini, A. (2020). Placement Optimization with Deep Reinforcement Learning. ArXiv.org. https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.08445

Tan, Z., & Mu, Y . (2024). Hierarchical reinforcement learning for chip-macro placement in integrated circuit. Pattern Recognition Letters, 179, 108–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patrec.2024.02.002

About the author

Vishal Ramamurthy

Based in the Bay Area, Vishal is a student at Carlmont High passionate about the applications of engineering principles and technology in our world today. His academic interests consist of computer science, engineering studies, physics and chemistry. Besides his academics, Vishal works on and develops engineering projects that have real-world applications such as XIMIRA LLC’s PHINIX mechanism to assist the visually-impaired with everyday life and a Python machine learning project that classifies cancerous breast tumors as malignant or benign. He has a deep interest in pursuing a career in engineering, particularly in the fields of electrical and computer engineering.