Author: Hillary Porco

Mentor: Dr. Reed Jordan

NSU University School

Abstract

The long-running socio-economic crisis in Venezuela has severely damaged public healthcare systems, which now face persistent shortages and restricted service availability. This research investigates Venezuelan patients’ healthcare challenges and their strategies for managing these obstacles, with particular attention to gender-specific barriers in service accessibility. The researcher conducted semi-structured interviews with 13 Venezuelan adults from different regions between July 14 and July 16, 2025. Interviews were conducted in Spanish through WhatsApp text and voice notes, then transcribed, translated into English, and pseudonymized. Inductive thematic analysis identified recurring patterns, while frequency counts determined the relative prevalence of each theme. Seven main themes emerged: medication shortages, poor public hospital facilities, insufficient specialist care, reliance on private healthcare services or HCM insurance, non-traditional medical approaches and foreign medication acquisition, preventive self-care measures, and community-based fundraising and support systems. Women described additional challenges accessing reproductive healthcare, managing chronic illnesses, and obtaining medical treatment outside their local areas. Current patient adaptation strategies—including preventive actions, unofficial support networks, and cross-border medication procurement—remain unstable and create unequal outcomes that affect women most severely. Policy priorities should focus on reliable medication supply chains, protected crossborder medical a

Keywords: Venezuela; healthcare access; qualitative interviews; women’s health; resilience; health systems.

1. Introduction

The public health system of Venezuela which used to rank as one of the best in Latin America has experienced a significant decline because of ongoing political instability, economic decline and hyperinflation (World Health Organization [WHO] 2023; Ortega et al. 2020). The healthcare facilities in Venezuela face ongoing problems with medicine, supply shortages, equipment breakdowns and massive healthcare worker departures to find better employment opportunities abroad (Doocy et al. 2019; Pan American Health Organization [PAHO] 2023). The healthcare system operates at reduced capacity because of these disruptions which force wealthier patients to seek private care or foreign medical services while low-income patients receive inadequate treatment (Rodríguez 2020; Hetland 2021).

The research examines how typical Venezuelans handle the structural failures that affect their healthcare system. The research investigates two main questions which are (1) What obstacles do patients face when they try to receive medical care in their daily lives? and (2) What strategies do patients use to overcome these barriers and how do women patients specifically handle these challenges? The research uses patient testimonies from 2025 to show the actual experiences that exist beyond official reports about system failures and it also provides a patient-centered perspective through its focus on their coping mechanisms and emotional responses which enhance existing quantitative and infrastructure-based studies of Venezuela’s healthcare emergency (Doocy et al. 2017; PAHO 2023).

This research has shown that hospitals face medicine shortages, stockouts and administrative breakdowns but it has not fully explored how patients make decisions when resources are scarce. The research connects these findings by showing how Venezuelans handle broken healthcare systems and how gender influences their treatment routes, women experience unique barriers to healthcare access because of their reproductive needs and caregiving duties. Limited mobility actually worsens their unequal healthcare opportunities. The analysis of gendered healthcare system performance under extreme economic conditions provides valuable knowledge about system breakdowns.

Research Questions:

- What barriers do patients in Venezuela encounter in everyday efforts to obtain healthcare?

- How do patients, particularly women, adapt to or circumvent these barriers?

2. Literature Review

Multiple research studies from national and international experts have documented the complete breakdown of Venezuela’s healthcare system. Multiple research studies confirm the severe state of infrastructure deterioration through reports about continuous medicine shortages, equipment breakdowns and even healthcare worker departures (Doocy et al., 2019; Ortega et al., 2020; PAHO, 2023; WHO, 2023). The public healthcare system which used to serve as a regional benchmark now operates with permanent shortages that force hospitals to stop vital services while patients must bring their own medical supplies. The healthcare system shows that major urban hospitals continue to operate at reduced capacity but peripheral medical facilities have lost almost all of their operational ability which results in major disparities between urban and rural areas as well as between different social classes (Rodríguez, 2020; Hetland, 2021).

Research on healthcare system collapse has led experts to study how patients experience medical care delivery in deteriorating facilities. The combination of unstable supply chains and currency fluctuations results in unpredictable access to vital medications according to Doocy et al. (2017) and Hetland (2021). The research community agrees that patients directly experience the consequences from both international sanctions and domestic governance problems although they disagree about which factor has the most impact. Households actually manage medicine shortages through three main strategies which include buying from informal markets and using remittances and implementing medicine rationing (Freitez, 2022; International Organization for Migration [IOM], 2022). The survival systems that Venezuelans create operate independently from official healthcare systems through parallel networks or function completely outside of them.

The current research on healthcare system failures provides essential information about large-scale breakdowns yet fails to examine how people and their families make independent decisions when facing scarcity at the individual level. Research using qualitative and feminist methods demonstrates that healthcare emergencies reveal existing gender-based social inequalities (Melo et al., 2023; Rueda-Salazar & García, 2024). The healthcare challenges Venezuelan women encounter stem from multiple factors which include reproductive care restrictions, family care duties as well as limited freedom of movement. The combination of financial constraints and shut-down specialized maternal facilities forces women to handle their pregnancies and also chronic diseases and family health crises without institutional backing. Research conducted in neighboring countries indicates that Venezuelan migrant women encounter equivalent healthcare obstacles because of their immigration status and social discrimination which demonstrates that gender-based healthcare disparities exist across international borders (Melo et al., 2023; Rueda-Salazar & García, 2024).

Academic researchers now employ resilience frameworks to study how people and their communities handle extended crisis situations. According to Norris et al. (2008) community resilience emerges from social networks and economic resources and information access which enable stress absorption. The survival of Venezuelans depends on individual resourcefulness as well as the support systems which include family networks and community structures and international connections. The research on Venezuelan families shows that they use remittances together with informal support networks and preventive self-care techniques to create their survival strategies (Freitez, 2022). The distribution of these survival strategies remains unequal due to people who possess foreign currency and have access to border travel and stable communication networks succeed in adapting better than those who do not.

Research on Venezuelan healthcare infrastructure deterioration has received extensive study but patient decision-making within Venezuela actually remains highly understudied. Most of the research found focuses on institutional breakdowns instead of showing how patients experience these breakdowns in their daily lives. The research combines patient testimonies with structural evaluations to show how women and other individuals handle healthcare access in a system that has stopped operating effectively.

3. Methods

This study used qualitative methods to explore Venezuelan patients’ experiences of healthcare access and adaptation under system collapse. Semi-structured, one-on-one interviews were chosen to capture the nuance of personal narratives and to be able to allow participants to describe their healthcare decisions in their own personal words.

3.1 Participants and Recruitment

The research included thirteen women aged 17 to 65 who participated in individual interview sessions. The researcher picked participants who lived in Venezuelan cities and mainly surrounding areas including Caracas, Guarenas, Maracay, Ciudad Bolívar and Valles del Tuy. The researcher was able to use trusted local contacts to find participants in June 2025 before they expanded the participant pool through WhatsApp using snowball sampling techniques; this method was selected because it helped achieve both geographic and socioeconomic diversity while safeguarding participants from political dangers in the unstable setting.

The study participants were all Venezuelan residents who received healthcare from the national system during the previous years. While the study excluded participants who lacked capacity to give consent or lived outside Venezuela. The study selected women as participants because their input was necessary for conducting gender-based research.

The three-day interview schedule from July 14 to July 16 2025 worked with participants’ work commitments and protected them from dangerous extended online sessions because of unreliable power supply. The researcher understands that snowball sampling could have brought social-network bias because people with restricted smartphone access became less probable to join the study. The Study Limitations section provides further information about these methodological restrictions.

3.2 Data Collection

The research team conducted Spanish-language interviews through WhatsApp text and voice calls from July 14 to July 16 2025 with each session lasting between 30 to 55 minutes. The platform enabled participants to interact at their own pace while ensuring their safety through asynchronous communication. The interview guide asked participants to answer open-ended questions about their care-seeking actions, their experiences with medication access, healthcare facilities, specialist availability and their financial approaches and their coping strategies.

The researcher conducted a pilot test of the interview guide with two Venezuelan contacts to verify both cultural understanding and language precision. The participants gave their consent through WhatsApp messages of all interviews while bilingual reviewers checked the accuracy of the English translation to preserve the original meaning which confirmed their willingness to participate and their ability to leave the study anytime. The transcription researcher substituted all personal information with pseudonyms to protect participant confidentiality.

3.3 Ethical Considerations

The research followed all necessary ethical guidelines for qualitative studies with low risk while the participants received information about digital communication privacy risks in Venezuela while being told to keep hospital names and official identities undisclosed. The researcher stored all data through encrypted files which required password protection and immediately removed identifying information from translated transcripts. The researcher also did not offer any payment to participants because they wanted to protect them from external influences in a region with limited resources.

3.4 Data Analysis

The researcher conducted inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to find recurring patterns and categories. The researcher performed multiple readings of transcripts for familiarization before using line-by-line coding to produce initial codes which later became broader thematic categories. The researcher examined candidate themes throughout the complete dataset to develop them into final themes while creating analytical memos for support.

The researcher documented all coding choices in a very detailed audit trail while performing negative-case searches and by also maintaining reflexive notes about positionality and translation decisions.The study’s exploratory nature required a single coder to analyze data while reflexive documentation replaced traditional intercoder reliability assessment.

4. Results

The research study found seven core themes which demonstrate how Venezuelan patients handle their healthcare needs in a system that lacks stability and has broken down into seven separate parts. The themes show how patients experience multiple forms of scarcity, adaptation and inequality which demonstrate both the complete breakdown of official healthcare services as well as the development of survival methods outside formal care. The following section presents an overview of theme distribution and relationships through Figures 1 and 2 before moving to the detailed analysis.

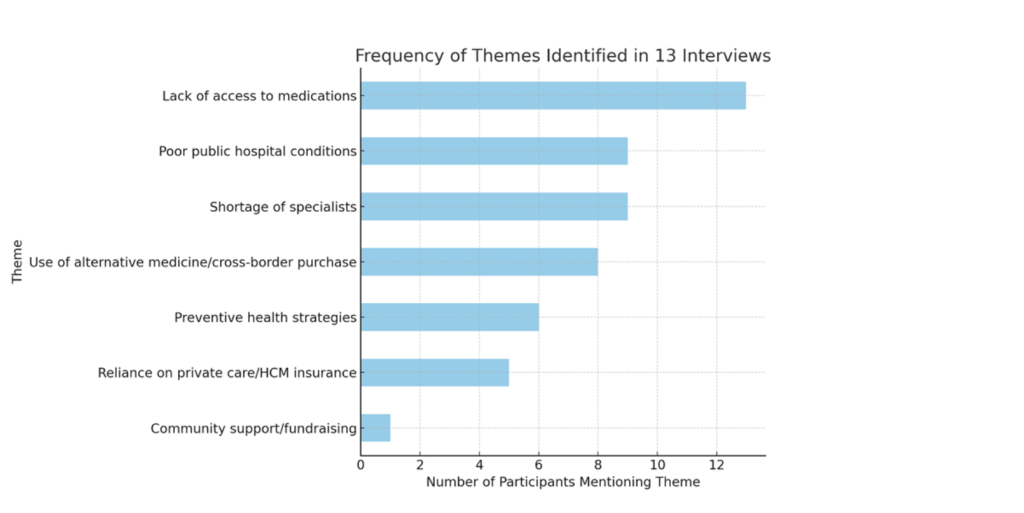

Figure 1 presents a frequency chart showing how often each of the seven themes appeared across the thirteen interviews. All participants discussed medication unavailability but specialist shortages and substandard public hospital conditions were mentioned by most many participants. The frequency chart in Figure 1. The themes of preventive health behaviors and private insurance use emerged less often but generated intense emotional as well as social responses. The visual data shows that scarcity-related problems took center stage in participant experiences while serving as the foundation for their coping mechanisms.

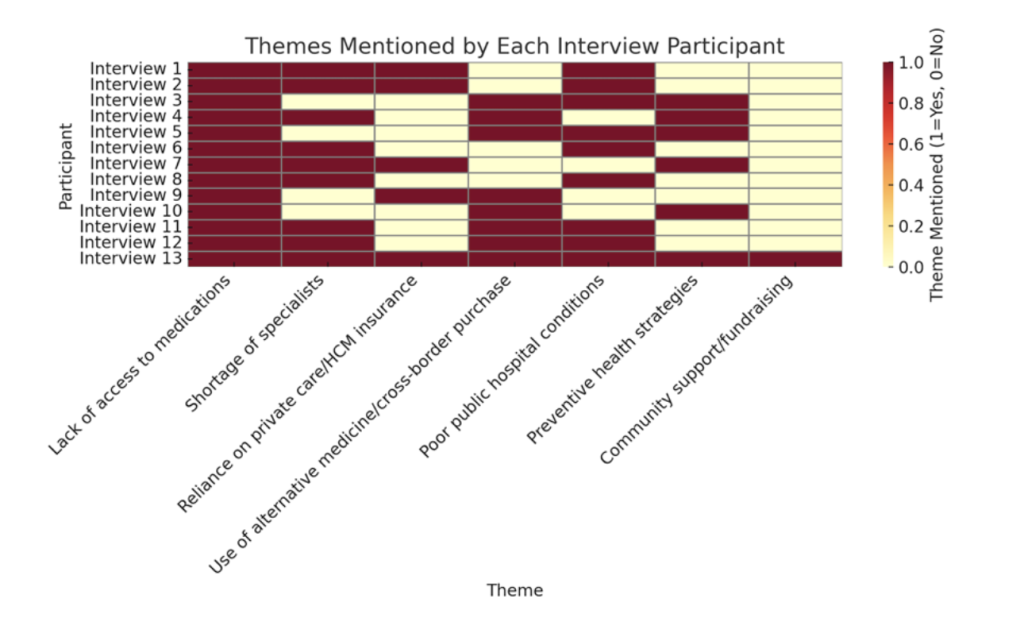

The binary-coded matrix in Figure 2 shows which seven key themes each of the thirteen participants discussed during their interviews. The left column contains participant identification numbers which match the thematic categories found in the right columns. The maroon filled cells in the matrix indicate participants discussed specific themes while yellow cells show their absence. The visualization shows that participants experienced both common barriers like medication shortages and less common challenges related to community fundraising and also preventive self-care. The chart demonstrates how different participants experienced various structural barriers at different levels which reveals how coping strategies spread unevenly throughout the healthcare system collapse.

4.1 Theme 1→Medication Unavailability

The thirteen participants in the study all described their ongoing struggles to get necessary medications through Venezuela’s public healthcare system. The participants identified medication shortages as their main obstacles which made it difficult to treat hypertension, diabetes, Parkinson’s disease and even asthma.

The woman from Nueva Casarapa explained that her friend received no medical supplies during her pneumonia hospitalization because her family needed to purchase all necessary items including gloves, she stated “the experience made me lose faith in the public healthcare system.” The patient population learned to accept that hospitals would only offer physical care facilities.

A healthcare provider at Guarenas Hospital stated that medications remain the hospital’s top priority but the supplies never reach on schedule. The resident of Ciudad Bolívar described how his grandmother suffered from severe leg pain because the hospital lacked any pain medication. The testimonies demonstrate how the official supply system has failed to deliver basic pain medication which causes emotional distress to patients.

The scarcity situation made people change their daily routines according to multiple participants. The high prices and unavailability of products in Valles del Tuy forced residents to share their medication and reduce their dosage for extended usage. The practice of medicine supply management through informal prescription sharing and dose reduction demonstrates both creative problem-solving as well as very high risk dangerous consequences because families had to stretch their limited medication supplies.The participants chose to purchase medications from outside their country because they had no other options left.

The mother from Maracay described her experience of buying medicine in Cúcuta after her son developed asthma because the hospital refused to provide oxygen, “the experience made me understand that we needed to leave the country.” The situation forced her to migrate to Colombia with her family after she obtained medication in Cúcuta.

The participants from different areas shared similar experiences about medicine shortages which they viewed as both a system failure and a heavy emotional and moral challenge. The participants displayed three main emotional responses to the situation: they worried about their family members’ worsening health and felt responsible for their inability to help and even lost faith in the healthcare system they used to trust. The widespread nature of these accounts demonstrates that medicine shortages represent both a national healthcare emergency and a personal indicator of Venezuela’s failing healthcare system.

4.2 Theme 2 →Substandard Public Hospital Conditions

Nine participants painted a grim picture of the extent to which Venezuelan public hospitals were very overcrowded, dirty, chronically under-resourced and unsanitary. Together, their accounts offer a glimpse into how systemic infrastructure failure has transformed the very meaning of hospital care from a site of treatment to one of uncertainty and survival.

A Guarenas woman described, “In public hospitals it’ s a mess, there are too many patients, no medicine, and sometimes not even water. And you sit there for three hours only to be told there’ s no specialist available.” Her experience is a mirror of the common experience of trying to work one’s way through institutions which can no longer maintain minimum standards of hygiene or even effectiveness.

A third participant from Caracas shared her mother-in-law’s ordeal after falling: “There, at Salud Chacao, they took an X-ray and said there was no traumatologist, we had to carry her across town to El Llanito and there were not even painkillers. Imagine seeing an old person in pain and being told there’ s no basic pain medicine.” This accounting of pain shows how staff shortages and supply deficits are magnifying suffering ushering routine emergencies into the territory of traumatic scourge.

A health-office worker who used to oversee public-sector spending gave an infrastructure-oriented explanation: “I could look at paper and see how little money was given versus what communities needed. This was always a gap between what people needed and what they could get.” And her double identity as administrator and patient bridges personal experience as well as systemic dereliction.

Some also relayed what they had seen of medical personnel being run ragged with unmanageable work duties where one woman said, “You see a doctor alone trying to assist 20-something people with not one glove nor disinfectant, absolutely nothing. After hours of waiting, most leave without being seen.” In the eyes of patients, these images of sick and very exhausted staff serve as visual reminders that the public health system had tragically caved from within.

In all of these stories, public hospitals serve as concrete avatars for Venezuela’s broader institutional collapse as respondents didn’t depict them as isolated failures but rather demonstrated how they were the product of visible outcomes from a chronic underinvestment, staff migration, and bureaucratic rot. Their stories demonstrate how systemic failure undermines trust by forcing patients to rely on private clinics or informal options whenever they can.

4.3 Theme 3→Specialist Shortages and Delays

Most participants described long waiting times and difficulty accessing medical specialists such as cardiologists, neurologists, and oncologists. These delays were not isolated inconveniences but structural outcomes of Venezuela’s shrinking medical workforce and deteriorating hospital capacity as participants consistently framed these shortages as both a medical as well as psychological burden turning treatable conditions into prolonged uncertainties.

A man from Caracas recounted, “My mother had tachycardia. At the emergency room, the EKG machine wasn’t working and there was no cardiologist. We had to take her to a private hospital.” His story reveals how technical failures and missing personnel really forced families to seek private care regardless of their financial hardship.

A former Indigenous Health Office employee offered a similar account from the administrative side: “My father needed a cardiology exam. Every hospital said the same thing, the machine was broken, or the technician wasn’t there. In the end, we had to pay privately, and my family had to pool money just to make it happen.” Her testimony links institutional scarcity to unequal outcomes where access depends on financial capacity rather than the patients medical needs.

Another participant from Caracas recalled the fatal consequences of these delays: “We took my mother to Vargas Hospital for an emergency. They didn’t even run tests, they just said she was fine and sent her home. Two days later, she died. I can’t explain the anger and pain.” Her account conveys the moral, emotional toll of systemic neglect as well as the collapse of clinical accountability.

For others, the absence of specialists created a cycle of deferred care. A participant from Valles del Tuy summarized, “If you need a specialist, you travel to Caracas, wait weeks, and still might not get seen. People just give up.” These accounts show how spatial and temporal barriers combine to make even basic specialist consultations inaccessible.

Together, these testimonies portray specialist scarcity as both a symptom and a driver of broader healthcare inequality. The inability to access specialized treatment deepens existing vulnerabilities, particularly for older adults and those managing chronic illness. Specialist shortages thus stand as one of the clearest indicators of Venezuela’s fractured health infrastructure where time itself has become a form of rationed resource.

4.4 Theme 4→ Reliance on Private Care or HCM Insurance

As public healthcare deteriorated, many participants described shifting toward private clinics or even employer-sponsored insurance programs known as HCM (Hospitalización, Cirugía y Maternidad). This reliance on private coverage emerged not as a preference but as a survival strategy as an adaptation to the state’s withdrawal from healthcare provision. Participants’ narratives show that while private access provided greater reliability it also reinforced very deep financial inequalities and excluded those without stable employment.

A woman from Guarenas explained, “When my neighbor couldn’t get care in the public hospital, she went to a private clinic. It cost her everything she had, but at least she was treated. People say, ‘If you want to live, you have to pay.” Her statement captures both the necessity and resentment surrounding privatized care.

Several participants reported prioritizing jobs that offered HCM insurance as a healthcare worker from Caracas shared, “I took a position mainly because it included private health insurance. Public hospitals don’t have medicine or equipment, so you end up needing HCM for even basic care.” Insurance thus functioned as a form of social capital, one that actually determined not only medical outcomes but also employment choices.

Another participant highlighted the limitations of such plans: “Even with HCM, you still pay a lot out-of-pocket. The coverage runs out fast, and the prices keep going up. It’ s like having a lifeboat with holes in it.” Her metaphor reflects the precariousness of middle-class adaptation under crisis conditions.

For women, these disparities were compounded by reproductive health needs. A participant from Caracas noted, “There’ s almost nowhere left for gynecological care unless you pay privately. Public hospitals cancel appointments all the time, and traveling far alone doesn’t feel safe.” Her account illustrates how gender, safety, and mobility intersect to limit care options even for those with insurance access.

Across these testimonies, private healthcare appears as both refuge and reminder of inequality. While HCM coverage temporarily shields patients from systemic failure it simultaneously deepens divides between those with institutional protection and those without as participants portrayed this duality with ambivalence gratitude for access mixed with anger that survival had become conditional on wealth or employment.

4.5 Theme 5→Alternative Practices and Cross-Border Procurement

When official healthcare systems failed many participants described turning to alternative remedies and informal medication channels to manage illness. These adaptations ranged from home herbal treatments to complex cross-border purchasing networks coordinated through many relatives abroad. The accounts portray a spectrum of creativity and desperation which are strategies that temporarily alleviated suffering but also carried risks of misinformation and even inequity.

A woman from Guarenas shared, “People started using natural medicine as teas, herbs, whatever helped. We learned recipes from neighbors or online because the pharmacies were empty.” Her story highlights how traditional knowledge re-emerged as an informal safety net when biomedical options vanished.

A healthcare worker from Caracas described a similar pattern of cautious substitution: “When medicines disappear, you do what you can use home remedies, eat healthy, try to stretch the little medicine you have left. It’ s survival.” This pragmatic tone resignation without illusion echoed through many interviews.

For others, adaptation required geographic movement. A mother from Maracay who had ultimately migrated to Colombia, explained, “Every few months, someone from our neighborhood crossed the border to buy insulin or antibiotics. We all pitched in money and sent lists. Sometimes they came back empty-handed; sometimes they didn’t make the trip.” Her narrative shows how scarcity created collective networks of cross-border cooperation grounded in trust and necessity.

Participants viewed these alternative strategies ambivalently: they provided temporary control but also underscored dependence on unstable, unregulated systems. A man from Valles del Tuy summarized, “You feel proud that people find ways to survive, but also scared—because it shouldn’t be this way.” His reflection captures the tension between resilience and resignation that runs throughout the data.

Ultimately, these testimonies reveal that informal and transnational health practices have become integral to everyday survival in Venezuela. Yet the uneven access to information, money, and cross-border mobility means that such coping mechanisms often reproduce the very inequalities they are meant to alleviate.

4.6 Theme 6→ Preventive Health Behaviors

Six participants described developing preventive health routines as a way to reduce dependence on Venezuela’s collapsing medical infrastructure. With hospitals being unreliable and medicines scarce many prevention became a deliberate survival strategy as a an attempt to regain control in an unpredictable environment.

Participants framed these lifestyle adjustments not as wellness trends but as pragmatic risk management.A woman from Guarenas explained, “I try to eat well, exercise, and meditate. During the hardest years, when medicine disappeared, that was all we could do.” Her statement reflects how self-care practices became substitutes for unavailable treatments.

A healthcare worker from Caracas expressed a similar sentiment: “You learn to avoid getting sick. I rely on my job’ s small clinic, but mostly I take care of myself because public hospitals are too dangerous.” The combination of precaution and fear shows how prevention emerged from distrust rather than health promotion.

Another participant from Venezuela’s Indigenous Health Office connected this shift to structural awareness: “After seeing how little funding there was, I started saving money for emergencies and taking vitamins. Prevention is cheaper than depending on the system.” Her comment reveals an economic logic to self-care, framing it as an investment in personal resilience.

Across these accounts, preventive health practices carried both empowerment and burden; they offered participants a sense of agency yet simultaneously transferred responsibility from institutions to individuals. A man from Guarenas summarized this trade-off: “It’ s good to be healthy, but it’ s also exhausting because you’re doing the government’ s job.”

These narratives highlight the privatization of risk at the household level and prevention, once a public-health goal, has become an individual coping mechanism as a an act of necessity shaped by structural abandonment.

4.7 Theme 7→ Community Fundraising and Support Systems

When formal health systems broke down the respondents narrated seeking solutions through traditional and informal medicine for their ailing bodies. These adaptations covered different levels, from herbal treatment in the home to intricate transborder shopping strategies passed on through relatives living abroad. The accounts reflect a range of creativity and desperation strategies that offered such temporary relief while also posing the risk of misinformation, expense, and inequality.

One health-care worker in Caracas said that these were part of the gradual process of standing-in: “You do what you can because when medicines vanish from the store shelves, you have to treat yourself at home and eat healthfully and stretch out the last bit of prescription drugs. It’ s survival.” This pragmatic coarseness of resignation without illusion sounded through many interviews.

Others had to move geographically to adapt, “From time to time, someone we knew would go over and buy insulin or antibiotics,” said a mother in Maracay who eventually relocated to Colombia. “We all chipped in money, and we sent lists. Sometimes when they went out in the morning, they didn’t come back with anything; sometimes they never left.” Feign’s story illustrates how the scarcity generated cross-border networks of collective action based on trust and mutual need.

Such alternatives were actually only weakly accepted by the participants; in a way as they gave temporary power but at the same time repeated and underlined an insufficient dependency on unstable, unregulated systems. A man from Valles del Tuy put it like this: “You feel proud that people are finding ways to survive but also scared because people shouldn’t have to do things this way.” His reflection is a poignant tension between that of resilience and resignation that courses through the data.

Ultimately, these testimonies illustrate that informal and transnational health practices are now central to everyday survival in Venezuela but the unequal ability to access information, money, and cross-border mobility means that these coping strategies can themselves replicate the inequalities they are intended to ameliorate.

5. Discussion

5.1 Understanding Patient Adaptation Through Resilience

The research results show that Venezuelan patients’ healthcare collapse experiences extend beyond institutional breakdowns because they demonstrate intricate social and psychological adaptation patterns which align with resilience theory. According to Norris et al. (2008) community resilience exists as the ability of social systems to withstand disturbances while keeping their fundamental operations intact. While according to Ungar (2018) resilience emerges through the continuous interaction between personal initiative and environmental resource availability. The presented stories show Venezuelans performing both individual adaptation and social environment boundary adjustment at the same time.

The coping strategies of participants including preventive health practices and informal medication distribution and private insurance usage and community-based fundraising efforts demonstrate the interconnected systems which Norris and Ungar describe. People use “navigation and negotiation” according to Ungar to find or even establish alternative resource access routes when faced with restricted circumstances. The adaptive strategies people use to cope with their situation demonstrate how digital networks function as a replacement for missing state-based infrastructure. The adaptive capacity shows uneven distribution patterns among the population. The research supports Norris et al. (2008) who state that resilience depends on four essential domains which include economic development and social capital and information and community competence yet these resources remain unevenly accessible in present-day Venezuela.

The research indicates that patients demonstrate remarkable resourcefulness but their adaptive actions take place within systems that maintain significant social inequalities. Women encountered multiple barriers which restricted their ability to join resource-sharing networks because they faced limitations in mobility and safety and reproductive healthcare access. The anthropological concept of “bounded resilience” describes their situation because they showed bravery through adaptation yet their actions remained restricted by structural barriers.

The research evidence contradicts positive views about resilience as a solely empowering force and it also reveals that people must take on institutional responsibilities when public institutions abandon their duties which results in resilience becoming a sign of systemic failure. The Venezuelan patients’ ability to adapt serves as proof of human flexibility yet it also reveals the unacceptable circumstances which force people to endure such hardships.

5.2 Gendered Vulnerabilities and Health Inequality

The research findings from women participants demonstrate that gender plays a fundamental role in determining how Venezuelan women experience the collapse of their healthcare system. Women took on dual responsibilities by providing care to their families while simultaneously acting as medical coordinators who located medications and arranged transportation and handled healthcare costs. The gendered tasks women performed during this time increased their stress levels and financial difficulties which strengthened existing social and economic inequalities.

A woman who lives in Caracas described her multiple responsibilities when she stated, “You need to perform all nursing duties and medical tasks and psychological support and financial management for your family members.” The statement demonstrates the “care work paradox” which feminist scholars describe as women taking on unpaid work to replace absent institutional care according to Hochschild (1995) and Tronto (2013).

The research data indicates that women experienced different levels of risk because of their reproductive and chronic health requirements. Women participants explained that they experienced prolonged delays when trying to obtain gynecological care and birth control methods and prenatal medical assistance. The participant described her experience of seeking gynecological care in Caracas because she needed to travel long distances but doctors frequently canceled her appointments.

Women who are pregnant or have medical issues must handle their health needs independently because they lack proper care. The breakdown of healthcare systems leads to increased health dangers for women and restricts their ability to control their bodily autonomy. Women encountered special risks when seeking medical care because they needed to navigate dangerous areas while dealing with transportation problems and security threats. The participant from Maracay expressed her fear about needing Caracas treatment because bus services were unavailable. The combination of gender with geographical location and security risks produces what scholars call “layered precarity” (Butler, 2016) which restricts women’s ability to make decisions.

Women showed impressive organizational abilities despite facing numerous obstacles in their community such as organized medicine-sharing programs and operated online fundraising campaigns and distributed health information through WhatsApp messaging. Women’s ability to solve problems through resourcefulness continues to perpetuate the societal norm that they should handle institutional breakdowns through emotional work and logistical management. The participant expressed her question about why mothers consistently need to find solutions for every problem.

The research results support feminist anthropological theories which demonstrate that health emergencies reveal and intensify existing social inequalities as the social structure of gender determines how people experience risk exposure and healthcare access. Women in Venezuela experience both the power of their social connections and the weight of enduring a healthcare system that ignores their needs.

5.3 Policy Implications and Structural Change

The healthcare crisis in Venezuela exists beyond resource shortages because it stems from fundamental problems with system organization and unequal distribution of resources. The solution to these problems needs both emergency policy solutions and enduring structural changes to healthcare systems as the healthcare system needs to focus on these essential priorities that participants identified to rebuild trust and minimize gender-based and geographic healthcare inequalities.

The healthcare system needs to create dependable systems for medication distribution across the country. The participants in this research study all mentioned their struggles to get necessary medications which proves that Venezuela needs better medicine procurement systems and improved distribution networks with monitoring capabilities for all regions. The stabilization of pharmaceutical access through international humanitarian organization partnerships should include oversight systems to stop diversion and corruption activities.

The government needs to create official programs that protect patients who need medical treatment outside their home country. The participants needed to use unofficial networks to buy medication outside their country which exposed them to dangerous situations and legal consequences. The government should also establish controlled humanitarian medication import systems through official agreements with Colombia and Brazil. The current system of private and dangerous medication procurement would become unnecessary through these policies.

The healthcare system needs to create immediate specialized outreach programs which focus on treating women and patients who need ongoing medical care. The research shows that women face the most severe health problems which receive insufficient attention during reproductive and preventive care. Mobile health units together with regional telemedicine programs should be implemented to provide better healthcare services in underserved areas while minimizing travel-related dangers. The implemented measures need to adopt gender-sensitive approaches which account for women’s dual responsibilities in caregiving and their limited mobility.

The protection of financial resources for healthcare services must become a priority to stop the growing separation between different social groups in healthcare access. The current healthcare system operates based on wealth because most people depend on private insurance (HCM) and pay medical expenses directly from their pockets. The health system needs more than technical fixes because it requires public trust to be rebuilt as the participants expressed their sense of being left behind and their complete emotional depletion. The recovery of public trust in healthcare institutions depends on transparent governance and professional retention strategies and community involvement in health planning processes. The success of well-designed reforms depends on rebuilding trust between healthcare providers and their patients because without it these reforms will fail to benefit the intended population.

The proposed recommendations follow the principles of resilience frameworks developed by Norris et al. (2008) and Ungar (2018) which state that recovery success depends on building up social and institutional frameworks at the same time. The combination of supply chain improvement with humanitarian channel legalization and gender-focused policies will enhance healthcare results while bringing back the lost sense of national security.

5.4 Study Limitations and Future Research

As with all qualitative inquiry, this study has several limitations that should guide the interpretation of its findings.

First, the sample was relatively small and although it reached regional diversity between age groups, it cannot be generalized to all women in Venezuela. The study’s aim was depth rather than breadth and its findings should not be taken as statistically generalizable but illustrative.

Second, recruitment occurred through WhatsApp networks and snowball sampling leaving out consideration of those without digital access or outside their social network. As a result, the lives of the most marginalized groups, like people in rural areas who do not possess smartphones or are in absolute poverty, may have been unaccounted for.

Third, the 3-day window of data collection precluded follow-up interviews or even longitudinal tracking. Further fieldwork over a longer term might show how coping strategies shift with continued economic or political changes.

Fourth, all interviews were translated from Spanish to English and some nuance may have been lost in translation despite the benefit of careful checking. Future research would gain from bilingual analysis or Venezuelan co-researchers to increase cultural and linguistic precision.

Lastly, the study focuses on gendered experiences and does not provide in-depth analyses of how class, ethnicity, and disability intersect. Future research could explore the interplay of these attributes with access to care and resilience strategies.

Despite these constraints, the study provides a valuable look at how average Venezuelans are dealing with a failing healthcare system. The uniformity of themes by respondents suggests that such issues are not few and far between and could be examined further through mixed-method or cross-regional designs.

6. Conclusion

The research investigates how Venezuelan patients experience the breakdown of their national healthcare system. The research used qualitative interviews with thirteen participants from different areas to document their daily experiences with medication shortages and insufficient hospital facilities and specialist shortages and their need to use private and informal healthcare services and the gender-based differences in healthcare access. The stories present a survival mechanism which people develop because of necessity which researchers term as resilience under constraint.

The participants demonstrate that their ability to cope with the situation exists without choice and has its limits as people and their families have developed survival methods through resourceful behavior, mutual support and personal sacrifices which demonstrate the moral and structural weaknesses of failed institutions. Women take on most of the responsibility for caring for others and managing healthcare services and maintaining household stability. The women’s community support work upholds social structures yet demonstrates how women consistently take on unpaid care duties because of societal expectations about their role.

The study uses resilience theory (Norris et al., 2008; Ungar, 2018) to demonstrate that adaptation depends on the availability of social, economic and informational resources which Venezuelan society distributes unfairly. The creative solutions patients develop show human capability but complete healing needs more than individual perseverance. The path to recovery needs people to work together while institutions must change and public trust needs to be restored.

The research joins multiple academic studies that analyze health emergencies as humanitarian crises while revealing their connection to social inequalities and governmental failures and ethical duties. The testimonies from participants demonstrate that resilience should never serve as a reason for the government to step away from its responsibilities. The recognition of resilience should lead to system reconstruction which will transform survival from improvised measures into an entitlement.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible by the generosity of thirteen Venezuelan participants who shared their life experiences, including some of their most challenging moments. I am deeply grateful to those who assisted with translating the Spanish interviews into English while preserving the integrity and emotion of each story. I also thank everyone who contributed to transcription and offered valuable feedback throughout the research process.

References

Braun, V ., & Clarke, V . (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Butler, J. (2016). Frames of war: When is life grievable? Verso Books.

Doocy, S., Page, K. R., de la Hoz, F., Spiegel, P., & Beyrer, C. (2019). Venezuela’s public health crisis: A regional emergency. The Lancet, 393(10177), 1254–1260. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30344-0

Doocy, S., et al. (2017). The humanitarian response to the Venezuelan migration crisis: Needs, coordination, and challenges. Journal of Refugee Studies, 30(3), 1–17.

Freitez, A. (2022). Household strategies and remittance dependence in Venezuela’ s economic crisis. Universidad Católica Andrés Bello.

Hetland, G. (2021). Crisis and inequality in Venezuela: The limits of redistribution. Latin American Perspectives, 48(1), 5–22.

Hochschild, A. R. (1995). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). (2022). Venezuelan migration and healthcare access report. https://www.iom.int

Melo, S., Rueda-Salazar, A., & García, P. (2023). Gendered health disparities among Venezuelan migrants in Colombia. Global Public Health, 18(2), 215–230.

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

Ortega, D., Guerra, J., & Salas, R. (2020). Public health and governance in Venezuela: Between collapse and adaptation. Revista de Salud Pública, 22(4), 501–515.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). (2023). Health in the Americas: Venezuela country profile. PAHO. https://www.paho.org

Rodríguez, F. (2020). The macroeconomics of Venezuela’s collapse. Center for Economic and Policy Research.

Rueda-Salazar, A., & García, P. (2024). Venezuelan women’s healthcare under migration and crisis: A comparative perspective. Journal of Migration Studies, 12(1), 88–104.

Tronto, J. C. (2013). Caring democracy: Markets, equality, and justice. New York University Press.

Ungar, M. (2018). Systemic resilience: Principles and processes for a science of change in contexts of adversity. Ecology and Society, 23(4), 34. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10385-230434

World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of): Health profile and key indicators. WHO. https://www.who.int

About the author

Hillary Porco

Hillary Porco is a senior researcher at NSU University School whose work centers on global health access, qualitative research, and health policy in Latin America, particularly Venezuela. She completed this project under the mentorship of Dr. Reed Jordan (NYU Public Policy) where her research interests include healthcare inequities, patient narratives, and community-based health systems. She intends to pursue a career in medicine and global public health.