Author: Lilya Elchahal

Mentor: Dr. Bart Bonikowski

The Westminster Schools

Abstract

This study investigates the impact of technology use and urbanization on cultural practices in Brazilian communities, with a focus on family routines, media consumption, and community engagement. Using a survey of 35 respondents from rural and semi-urban towns, data were collected on cultural habits during primary school and adulthood, technology usage, and urbanization-related variables such as commuting and town migration. Composite scales were created to measure cultural engagement and technology use. Results indicate a modest decline in traditional cultural practices, such as sit-down family dinners, while engagement with global media (European and U.S. films, music, and digital platforms) has increased significantly. Urbanization shows strong associations with decreased family meal frequency and community interaction, while technology correlates moderately with increased media consumption and online engagement. These findings highlight the nuanced role of modernization in reshaping cultural life: while traditional practices persist, they are increasingly supplemented or substituted by digital and urban influences. The study underscores the importance of considering both generational and technological factors when analyzing cultural change in contemporary Brazil.

1. Introduction

Latin American culture is quite diverse, complex, and representative of the region’s rich history. It is an amalgamation of indigenous, African, European, and Asian cultures. Of all the countries in Latin America, however, there is only one that does not have a Spanish colonial legacy. Brazil is now the only Latin American country where Portuguese is the official spoken language. It has long been known as a family-based culture, in which Brazilians widely celebrate Carnival, samba, and the national soccer team. Culture is a collection of the beliefs, practices, symbols, and rules of a people, which can be spread verbally or through practice. Culture is ever-evolving, shaped by rapid changes in economic, social, and political environments. Given these shifts, it is likely that new beliefs have emerged as part of this dynamic culture in recent years. These transformations raise an important question: to what extent have modern influences affected traditional cultural practices? Traditional practices include the impact of family-centered values on media representations and the emphasis on culinary traditions and festive holidays. Even though these traditional cultural norms continue to predominate in some parts of the country, globalization has introduced new influences. Consumerist culture, international mass media, and rapid advances in digital technology have altered consumption patterns, entertainment patterns, and even language use patterns, particularly among the younger population (Graham). Urbanization has also changed the way of life, blending traditional lifestyles with modern urban life and restructuring work, social, and cultural norms (Aldrich). As a result, traditional practices are being modified and redefined rapidly. While scholars generally agree that cultural practices are undergoing significant transformations, the extent of these changes and their relative significance—especially in Latin America—remain poorly understood (Caldeira). This study investigates how rapid economic, social, and political changes in Brazil have affected traditional cultural practices through ethnographic survey data.

Though modern consumer culture has certainly penetrated the economic markets of Brazil, introducing international brands, fast food, and digital technology, the exact extent of their influence on daily life—be it diet, leisure activities, or language—is unclear. Consumer culture refers to the lifestyle and social practices centered around the consumption of goods and services, heavily influenced by capitalism, advertising, and mass media in modern societies. Urbanization, particularly in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Brasília, has catalyzed a mixture of traditional Brazilian ways with cosmopolitan, contemporary lifestyles. At the same time, traditional cultural events such as Carnival continue to celebrate the classic parade, but incorporate international music, fashion, and lighting and stage design technology advances (Abreu). While Carnival is not native to the Brazilian indigenous population, it remains a popular celebration that is considered culturally important. Social media and the World Wide Web are connecting Brazilian society to the rest of the world more than ever before, allowing Brazilians to experience multicultural exchanges where they are both shaping and being shaped by global trends. This essay will examine the various degrees to which these forces of globalization, urbanization, and technology are influencing Brazilian culture in terms of lifestyle changes and time-honored practices. I will attempt to shed light on the extent to which these cultural changes are taking place, clarify their causes, and explore whether there are other hidden forces at play.

In this study, I will assess cultural change through four key concepts and their impact on rural Brazilian societies. The first concept evaluated is Cultural Practices, which include traditional norms, rituals, and social routines. To measure this, I will examine respondents’ frequency of having family meals, attending cultural events in their area, and engaging in religious or community activities. These behaviors will be coded into a scale to capture the strength and frequency of such behaviors, with survey questions asking how frequently participants have dinner with their families, attend cultural events, or visit local religious services or community events.

The second critical construct is technology use, reflecting the extent to which people use modern-day technologies, primarily in the context of media consumption, social media use, and access to information digitally. This will be measured via a “Technology Use” scale, for which participants’ responses related to the level of their media consumption—such as TV watching, browsing on social media, or reading news online—will be evaluated. Through these responses, I intend to measure the degree of technological embeddedness in participants’ lives and its potential influence on cultural habits.

The third concept is the effect of urbanization on individuals and the scale of migration from rural towns to urban cities. This will be reflected through analysis of factors such as how often respondents travel to cities, respondents’ migration experiences (e.g., whether they have migrated from villages to cities), and historical patterns of population density, which can serve as an urbanization proxy. It is essential to determine the extent to which migration and experience in urban settings could impact cultural practices and the adoption of technology in rural communities.

Lastly, I will analyze the effect of modern globalization on indigenous culture, specifically regarding the impact of media and technology on individuals’ lifestyle choices and values. Lifestyle refers to the habits, attitudes, and economic level that together constitute the mode of living of an individual or group. This will be quantified through respondents’ exposure to Western media (e.g., American movies, TV shows, or music) and activities most commonly associated with Western lifestyles (e.g., reading global media materials or keeping up with Western fashion). These factors will ensure an understanding of how Western cultural values and globalization can affect traditional cultural patterns. Globalization refers to the process of increasing interdependence and integration of the world’s economies, cultures, and populations. On the other hand, urbanization is the process of people moving from rural areas to cities and towns, leading to population growth and the expansion of urban centers.

The four key concepts—cultural practices, technology use, urbanization, and modern globalization in rural Brazilian societies—will help identify patterns in societal changes driven by these dynamic external influences. The survey conducted will investigate different correlation patterns between overarching variables to begin determining whether they impact cultural changes currently occurring.

2. Background

Brazil’s current cultural ecosystem is shaped by a complex interplay of urbanization, modern global influences from around the world, and technological advancements. While it is commonly agreed that such forces influence cultural practices and social norms, the question remains: specifically, how have they affected Brazilian culture, and among these forces, which are the most dominant? This is a significant question because even though cultural change is recognized, the exact mechanisms driving this change—the relative contributions of globalization, urbanization, and technology, in particular—are not yet adequately explored (Aldrich, Goldman, and Lipman 2004). Comprehending these nuances would help illuminate the magnitude of these changes and their impact on shaping the future of an important country such as Brazil.

With the early dominance of a slave and plantation economy and the 19th-century emergence of industrialization, Brazil has faced many shifts in its identity. Like the rest of Latin America, Brazil has been significantly influenced by global powers, such as the United States and Asia. Globalization, through media, consumerism, and a host of ideals, has contributed to a sense of cultural dissonance in Brazil (Madukwe and Madukwe). Notwithstanding, some developments, both present and future, influence Brazilian society in unique ways. For instance, multinational companies have promoted a more consumerist economy and materialistic culture, with both positive and negative consequences. This, in turn, has affected market dynamics and social interactions (Graham). The adoption of fast foods, fashion, and technology has brought drastic changes to society. Although these influences have contributed to the erosion of Brazil’s ethnic and indigenous cultures, they also reflect broader cultural adaptation. The breakdown of family structures, religious influence, and the impact of other cultures brought by globalization has been documented by numerous scholars (Caldeira). In Brazil, the weakening of extended family connections and the rise of individualism have profoundly affected lives, resulting in diminished communal relations, a shift toward more autonomous lifestyles, and the transformation of social support mechanisms (Hutchinson). This shift reduces the role of the extended family as a source of social support, encouraging individualism and reshaping community-based welfare.

Western legal systems, particularly in modern contexts, emphasize individual rights, whereas many traditional Western cultures (e.g., pre-industrial Europe) prioritize communal solidarity. However, the interaction of law and culture remains complex. Young generations are most vulnerable to cultural dissonance as they navigate global trends and traditions (Sibani). This manifests in their increased consumption of foreign films, street foods, and fashion. Older generations, conversely, may struggle to adapt to rapid cultural changes as they clash with traditional practices. Although youth are usually at the forefront of adopting new customs, they may also experience negative effects from losing valuable social elements native to their culture while embracing a more globalized lifestyle.

Urbanization has also transformed Brazilian culture, particularly in urban hubs such as Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, where rural-influenced culture mixes with urban ways of life (Chauvin). Migration from rural towns to cities has resulted in both cultural assimilation and conflict between rural customs and urban norms. The acceleration of urbanism is accompanied by changes in family structures. New nuclear family types have emerged due to increased mobility and independence (Liu). Traditional dependence on extended families, which historically provided both economic and emotional support, has decreased, leading to a more individualized family system. The heightened emphasis on nuclear families, particularly in urban areas, can contribute to social disintegration, as individuals rely less on extended families and more on nuclear families for support (Lai).

Urban lifestyles and attitudes continue to challenge conventional family values and communal affiliations, promoting ideologies centered on individualism and autonomy. Beyond socio-cultural effects, urbanization is associated with economic changes, such as a shift from pre-market to market economies (Villa). With Brazil’s transition to urban settlements, reliance on barter exchange or informal social support systems is diminishing, replaced by material culture. The transition to a cash economy and emphasis on personal wealth promotes competitiveness and social differentiation.

Technological innovation, particularly through social media and digital platforms, has had a significant influence on Brazilian cultural practices. Such innovations have introduced global culture into Brazilian households, accelerating the alignment of local practices with Western norms (Chung). Cross-cultural exchange has occurred for centuries via books, television, and film. However, digital media makes this exchange more direct, interactive, and immediate, with platforms such as Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube enabling real-time participation. Brazil both absorbs and projects global culture in ways not possible with older media (Stuenkel). Traditional festivities, like Carnival, have adapted to incorporate contemporary technologies such as advanced lighting and stage design (Graham). Digital communication devices have also altered social composition, particularly among younger generations, changing methods of communication, socialization, and relationship formation. Mobile technologies and the internet have revolutionized socialization and idea sharing, sometimes supplementing or substituting face-to-face interaction (Lai 2016). While these platforms provide global connectivity, they do not entirely replace in-person interactions but offer alternatives, facilitating rapid cultural exchanges. These changes have introduced new cultural patterns, including increased use of English in daily communication and alternative modes of cultural learning through videos and other digital media (Liu).

Tension persists between maintaining traditional Brazilian values and adopting globalized norms. Traditional practices remain valued but are increasingly modified or replaced by contemporary consumer practices and individual lifestyles. Younger generations, especially in urban centers, are more receptive to Western cultural norms, while older generations retain traditional values. This generational gap permeates family life. Despite globalization, some Brazilian cultural aspects, such as Carnival, demonstrate resilience.

Globalization is not merely the transfer of ideas, technologies, and goods across borders but represents a fundamental transformation of societies through the diffusion of global economic, cultural, and political structures (Sibani). Western values are often dominant, influencing not only material life but also local beliefs and traditions. The imposition of global political, economic, and cultural norms, particularly from the United States and Europe, has profoundly reshaped societies, frequently at the expense of local cultures and identities. One consequence has been the reconfiguration of traditional religions, belief systems, and social structures, which must adapt to remain relevant as new routines emerge. Although Brazil’s culture has always been dynamic, the pace of change induced by globalization, technology, and urbanization warrants closer examination. In Brazil, globalization is particularly evident in the shift toward individualism, materialism, and a consumerist lifestyle. The introduction of global media and consumer culture has significantly impacted daily life, particularly in urban areas such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Exposure to global ideologies, fashion, and technology has contributed to a decline in historically prioritized collective values, including familial reliance and communal unity. International brands, fast foods, and global attire have shaped social spaces and identity formation (Madukwe and Madukwe).

Social scientific literature suggests that technology, particularly social media and digital platforms, plays a larger role in promoting cultural change in Brazil than urbanization or Western influences. While urbanization and globalization contribute to cultural change, technology accelerates it by making global trends accessible and influential across all aspects of society, from communication to fashion. Digital technologies and social media enable the rapid dissemination of cultural practices and norms, altering social interactions and self-representation.

Younger generations are especially adept at adopting global influences, blending them with local practices, and modifying traditions such as Carnival or family norms. Technology fosters individualism, challenging Brazil’s traditionally communal values. Research indicates that young Brazilians, in particular, align with global digital cultures and adopt individualistic identities. Older age groups are more likely to adhere to traditional practices, and scholars suggest that this generational divide significantly shapes Brazilian culture. Despite these changes, Brazilian culture demonstrates resilience, balancing the adoption of modern technology with the preservation of traditional values. The ongoing negotiation between technological adoption and cultural preservation remains a critical area of research in understanding Brazil’s evolving cultural identity.

In conclusion, Brazilian culture has undeniably transformed in response to these forces, yet it retains remarkable resilience. The central challenge is reconciling modernizing influences, such as technology and globalization, with traditional cultural practices. As Brazil engages with globalization, it must navigate adopting modern innovations without sacrificing its cultural essence. Understanding how Brazilian culture adapts and evolves amid technological progress, while preserving its core customs, is essential for grasping the future trajectory of this vibrant society.

3. Data and Methods

To answer the main research question in this study, I conducted a survey to gather original data from Brazilian citizens living in rural towns and from diverse backgrounds. The survey aimed to collect information regarding cultural practices, social habits, technology use, and demographics. It was also designed to compare participants’ behaviors during their primary school years with their behaviors today. The survey was distributed online using a convenience sampling method and was completed by 35 participants. Respondents ranged in age from 18 to over 50 years old. The survey was available in both English and Portuguese to facilitate completion by participants with different linguistic backgrounds, including Brazilian and Brazilian-American individuals. All responses were collected anonymously. As a convenience survey, the sample was not randomly collected, which constitutes a potential limitation affecting the generalizability of the results.

The questionnaire was designed to capture information on cultural practices, social habits, technology use, and demographics, with a focus on comparing participants’ early primary school habits to their current behaviors. Questions addressed social habits, including family meals, media consumption, news habits, music preferences, attendance at cultural events, community engagement, religious practices, and technology use. The survey was divided into three sections: cultural practices, technology use, and demographics. All questions were formatted as multiple-choice items with pre-set response options. Completion time was approximately 10 minutes.

Demographic questions covered participants’ place of origin, gender, age, education, occupation, and marital status. Respondents were from various Brazilian towns, including Goiás, São Paulo, and Rio de Janeiro, as well as a small group of recent Brazilian immigrants to the United States, primarily in Georgia and Florida, who had immigrated within the last five years. The responses of immigrants were included in the analysis due to their frequent returns to Brazil and their careful understanding of the survey’s objectives. Regarding education, 33.3% of participants held a bachelor’s degree, and 22.2% worked in business or service occupations. The gender split was 60% male and 40% female, and most participants (55.2%) were married.

To assess the impact of technology use on cultural changes, I created scales for key behaviors related to cultural practices and technology use. This involved combining multiple questions measuring similar behaviors into composite variables. For example, responses on the frequency of family dinners, participation in cultural activities, and religious observance were aggregated into a “Cultural Engagement” scale. Similarly, responses on media use (movies, music, news) and social media activity were combined into a “Technology Use” scale. Urbanization was incorporated using variables such as proximity to large cities and migration history (e.g., moving from rural to urban locations). Population density over time was also used as a proxy for urbanization.

Once the scales were constructed, two-way tables were used to analyze data and examine relationships between technology usage and cultural behaviors to determine whether increased exposure to global media or technology influenced traditional cultural habits, such as family meal frequency or religious participation. The dependent measures focused on cultural change indicators, including frequency of family dinners, media consumption, and engagement in local community routines. Correlations between technology use, globalization, and urbanization scales with these dependent measures were analyzed. Descriptive statistics provided response frequencies for all variables, while two-way tables allowed assessment of relationships between technology use (e.g., frequency of social media use or online news consumption), cultural practices, and globalization. Additional variables such as education, age, and migration experience were examined to determine whether they shaped these relationships. This approach allowed identification of patterns indicating how technology, urbanization, or exposure to global cultures affected current cultural practices.

Several limitations of the study must be noted. Convenience sampling, small sample size, and the self-reporting nature of the survey constrain the generalizability of the findings. The non-random sample may not fully represent the broader Brazilian population, and the sample size of 35 limits statistical power. Additionally, self-reported data may introduce bias, as participants could respond inconsistently or inaccurately.

Analysis of the survey findings revealed trends in technology adoption, urbanization, and cultural practice interrelations in Brazilian rural areas. However, the extent of observed cultural change appeared less pronounced than anticipated. This may be a result of the limited sample and may not reflect the full scale of cultural change experienced in more isolated or traditional contexts. The sample, which included respondents already exposed to modern technology and urban influences to varying degrees, may underrepresent the magnitude of cultural shifts. All participants were raised in rural areas but had experienced modernization, either through media exposure or urban migration, potentially diluting the observable impact of cultural change.

This distinction is important when considered in the context of the theoretical model. Individuals raised in small, traditional rural villages—similar to those existing in the 1960s—would likely show more pronounced cultural changes due to globalization, technology, and urbanization. By contrast, participants in this sample, who were already influenced by these factors during childhood, exhibited only modest changes. Thus, the muted cultural change observed is likely due to gradual exposure rather than the absence of change.

The relatively moderate findings should be interpreted cautiously. While the data provides insight into the effects of technology and urbanization on cultural practices, the scope of change may be less dramatic than in populations with more traditional lifestyles. Future studies involving participants from isolated communities or longitudinal studies tracking individuals over time would provide stronger evidence of the magnitude of cultural changes driven by globalization and technological advancement. Despite these limitations, the survey data offers valuable preliminary insights into technology use and cultural practices among rural Brazilian communities. This exploratory research can serve as a foundation for more representative studies and provide informative background for understanding trends within these populations.

4. Results: Descriptive Statistics

To begin examining cultural change, particularly regarding family dinners, 80 percent of respondents reported having a sit-down family dinner each day during their primary school years. This figure decreases slightly in adulthood, with 73.3 percent now having family dinners regularly, either daily or a few times per week. However, this shift may not directly indicate a cultural transformation. It could instead reflect life-stage factors. As individuals grow older, increased responsibilities—such as work, extracurricular activities, and travel—often interfere with the consistency of shared family meals. Therefore, while there is a measurable decline, it is crucial to consider whether this change results from cultural globalization or simply natural changes in daily routines.

Concerning media consumption, which reflects aspects of globalization, noticeable changes are evident. During their primary school years, 46.7 percent of respondents watched European or American shows a few times per week. Today, 50 percent watch them regularly, with 36.7 percent doing so daily. Music consumption from the same regions shows a similar pattern. While 40 percent listened daily in childhood, 53.3 percent now do so either daily or several times per week. These trends suggest a deepening integration of Western cultural products into daily Brazilian life, likely facilitated by increased access to global streaming platforms and digital media.

However, international news consumption requires more critical interpretation. Only 20 percent of respondents engaged with news from the United States and Europe daily during childhood. This figure increases to 40 percent in adulthood. While this appears to represent a meaningful shift, it is important to recognize that young children typically consume limited news, regardless of cultural context. To strengthen this analysis, comparing this with Brazilian news consumption during the same early period would help clarify whether the difference reflects content preference or age-related behavior.

In terms of traditional cultural practices, consumption of Brazilian food has remained consistently high. About 93.3 percent reported eating traditional meals daily during primary school, and 80 percent continue to do so today. Religious participation, however, shows a notable decline. During their early years, 43.3 percent of respondents attended services regularly. Today, 20 percent report that they rarely or never participate in religious activities. This shift may indicate a move toward secularization, though further demographic analysis would help clarify whether age or gender plays a role.

Perceptions of Carnival have also shifted over time. While 70 percent of respondents considered it important in childhood, only 13.3 percent now rate it as “very important.” Sixty percent still consider it “important,” but the overall decrease in enthusiasm may reflect generational changes in values or evolving regional traditions. Breaking this data down by demographic variables such as location, age, or exposure to global events could help identify factors influencing this change.

Community interaction offers additional insight. During primary school, 73.3 percent of respondents regularly interacted with neighbors and local communities. This strong sense of engagement likely stems from the rural or close-knit environments in which many participants grew up. Today, only 31 percent report daily engagement with their communities. This reduction may be attributed to urbanization and lifestyle changes rather than globalization directly. The shift from face-to-face interactions to digital connections may also play a role, particularly as individuals move to more urbanized and individualistic settings. In this case, community interaction functions as a dependent variable, reflecting cultural change within local environments.

Perceptions of migration trends further illuminate social and cultural transformation. For example, 13.3 percent of respondents strongly agree that people from their hometowns often move to larger cities such as Brasília or São Paulo. Additionally, 44.8 percent estimate that about half of their current community members are not native to the area. These migration patterns suggest increasing urbanization and mobility, which can shift local cultural identities and increase exposure to global cultural practices. Exploring whether individuals who have migrated themselves show higher engagement with globalized media or technology would add depth to this analysis.

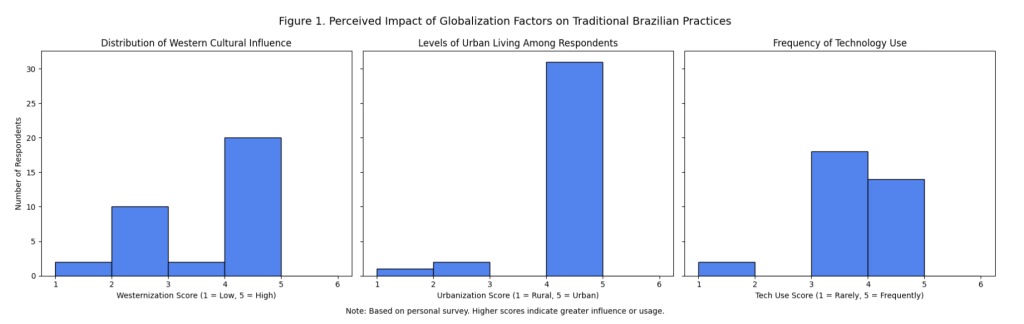

Technology use and social media engagement provide some of the most striking evidence of globalization. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of responses related to technology use, urbanization, and Western cultural influence, offering visual support for the trends discussed. About 43.3 percent of respondents agree that technology has significantly impacted their communities. Daily social media use is widespread, with 40 percent spending two to three hours per day on these platforms and another 40 percent spending five or more hours daily. Furthermore, 69 percent obtain their news primarily from the internet, and nearly all respondents (93.1 percent) conduct banking online or via mobile applications. These behaviors highlight how global technology platforms have become deeply embedded in daily life. To better understand the scope of this influence, breaking down the data by age and gender would clarify whether specific groups are more affected by or engaged with these digital tools.

5. Results: Associations Between Globalization, Urbanization, and Technology Use with Cultural Change.

In order to determine relationships between variables, I compiled three pairs—MoviesNow vs. MoviesThen, FamDinnerNow vs. FamDinnerThen, and NewNeighbors vs. OldNeighbors—representing major shifts in behaviors over time. These dependent variables reflect changes in media consumption, family routines, and community engagement, respectively. Their variation over time provides insight into how broader social forces, particularly urbanization and technology use, might be influencing cultural practices.

MoviesNow vs. MoviesThen examines the frequency of watching European and American films or television shows now compared to during primary school. While the majority of responses initially showed stability, indicated by zero values, there was a noticeable upward trend in later responses marked by increasing “1” scores. This trend suggests a shift toward more frequent engagement with global media content. One possible explanation for this change is the proliferation of digital streaming platforms such as Netflix, YouTube, and other on-demand services, which provide wide access to international films and television. These services reduce barriers such as geography, cost, and scheduling, making global media more accessible than ever. While the correlation between technology use and this cultural change was moderate (0.51), it is important to consider the mechanisms by which technology facilitates cultural exposure. Personalized content recommendations and algorithmic tailoring foster deeper engagement with diverse media, which may gradually influence preferences and behaviors. Although causation cannot be confirmed without further statistical testing, these factors provide a plausible explanation for the observed association.

FamDinnerNow vs. FamDinnerThen shows a more complex pattern, with a mixture of zero and negative values. Negative values suggest a decrease in the frequency or enthusiasm of family dinners over time. This shift may be strongly associated with urbanization and the increasing consumption of technology. Urbanization is typically associated with fast-paced lifestyles, longer commutes, and changing family structures, particularly in urban environments where dual-income households and staggered work schedules are more common. These structural changes can disrupt regular family mealtimes. In addition, digital distractions such as smartphones and tablets can interrupt shared meals or reduce their perceived value. Family members may choose to eat alone while watching individual screens or engaging in online activities. The high correlation between urbanization and cultural change (0.84) supports the idea that these lifestyle factors are influencing communal routines. While statistical significance has not been established in this analysis, the observed association aligns with well-documented trends in urban life and digital media consumption.

NewNeighbors vs. OldNeighbors reveals a significant downward trend in neighborhood social interaction. Negative scores dominate the responses, indicating a decline in engagement with local communities over time. This trend may be attributed to both urbanization and increased technology use. As more individuals move into densely populated, transient city environments, community ties often weaken. People may relocate more frequently and feel less incentive or opportunity to build lasting relationships with neighbors. Technology also contributes by providing alternative forms of socialization, such as social media, online forums, and messaging apps, which often replace in-person interaction. These tools allow people to maintain connections beyond their immediate geographic area, further reducing the importance of local social networks. The strong correlation with urbanization (0.84) and moderate correlation with technology use (0.51) reinforce the possibility that these broader structural and technological changes are influencing how individuals relate to their local communities. However, the absence of statistical significance testing means these results should be interpreted cautiously.

The strongest associations are seen with urbanization, particularly regarding declining family meals and reduced neighborhood interaction. Technology use is moderately correlated and appears especially influential in shaping media consumption and changing modes of social engagement. Globalization shows a much weaker correlation in this dataset, suggesting that while global influences are present, they may not be as directly or measurably impactful in this specific sample. The influence of globalization may also be more subtle or indirect compared to the immediate lifestyle impacts of urban living and daily digital technology use.

Taken together, the changes observed in MoviesNow vs. MoviesThen, FamDinnerNow vs. FamDinnerThen, and NewNeighbors vs. OldNeighbors indicate that technology use and urbanization are the most significant external factors associated with changes in cultural practice. These shifts in entertainment consumption, family routines, and neighborhood interaction illustrate how larger structural and technological developments are influencing cultural values and social behaviors. While the data reveals strong associations, it is important to note that correlation does not imply causation. Furthermore, this study did not perform statistical significance testing, so while the trends appear meaningful, they cannot yet be considered definitive. Future research should apply inferential statistical methods to test whether these observed relationships hold across broader populations and to rule out the possibility of confounding variables.

6. Discussion and Conclusion

This research highlights the complex ways in which urbanization and technological advancement are associated with changes in Brazilian cultural and social life. While the survey data shows correlations between these external forces and shifts in cultural practice—particularly in areas such as family dining and neighborhood interactions—it is important to recognize the limitations of the methodology. Correlation does not imply causation, and the self-reported, retrospective nature of the survey cannot definitively explain the causes of these cultural shifts. However, when interpreted alongside existing literature and broader global trends, the findings offer insight into possible mechanisms through which urbanization and technology may be reshaping cultural norms.

The decline in family meal frequency and the weakening of neighborhood social ties observed in the data are patterns consistent with existing research on the social effects of urban living. Scholars have long documented that as societies urbanize, traditional communal structures tend to erode due to increased geographic mobility, demanding work schedules, and spatial reorganization of daily life. In Brazil, the rapid expansion of cities has introduced pressures that disrupt conventional family routines and reduce the frequency of informal community interactions. The strong correlation (0.84) found between urbanization and cultural practice change in this study supports these findings, suggesting that people living in urban environments may be more likely to adopt lifestyles that prioritize individual autonomy over collective ritual.

Technology use also appears to play a significant role in reshaping cultural practices, albeit with a more moderate correlation (0.51). As digital devices and internet access become increasingly integrated into everyday life, patterns of media consumption and social engagement shift accordingly. The rise of social media platforms, online entertainment, and personalized digital environments can create a sense of virtual connection that may, paradoxically, reduce face-to-face interactions within the immediate community. This aligns with the observed decline in neighborly interaction and the substitution of communal activities with individualized digital experiences. Although the survey does not directly measure time spent on digital platforms or social network engagement, these trends are widely reported in other studies and offer a reasonable explanation for the patterns seen in the data.

It is important to emphasize that the observed associations should be interpreted with caution. The study does not include tests of statistical significance, and the retrospective nature of the survey introduces possible memory bias or inaccuracies in self-reporting. In addition, the sample may not represent the full diversity of Brazilian society, particularly rural communities or regions with lower technological penetration. Thus, while the findings suggest important patterns, they should be considered exploratory and preliminary rather than conclusive.

Nonetheless, these results contribute to a growing body of work examining how globalization, urbanization, and technology intersect to transform cultural life. For example, although urbanization and technology appear to be contributing to the erosion of traditional practices, they also present opportunities for cultural reinvention. Technological tools can support cultural preservation through digital archiving, online storytelling, or virtual celebrations of national events like Carnival, enabling new forms of participation and innovation. This dual nature—where culture is both challenged and renewed—emphasizes the need for adaptive cultural frameworks that can absorb change without losing core values.

To build on this research, future studies should investigate generational patterns in cultural adaptation, especially how different age groups experience and negotiate technological and urban pressures. Comparative studies across urban and rural contexts within Brazil could reveal the extent to which these dynamics vary based on infrastructure, community size, or economic development. Moreover, qualitative methods such as interviews or ethnographies could help uncover the lived experiences behind these trends, providing richer context that surveys alone cannot capture.

Beyond Brazil, the patterns observed here are relevant to many societies undergoing rapid urban growth and digital transformation. In global terms, the tension between tradition and modernity is increasingly shaping policy debates about cultural preservation, social cohesion, and identity. Understanding how these macro-level forces influence daily life can inform initiatives aimed at promoting cultural resilience. Resilience, in this context, refers not only to the preservation of traditions but also to the capacity to adapt cultural expressions in ways that remain meaningful amid social change.

In conclusion, while the findings of this study suggest that urbanization and technology use are strongly associated with cultural changes in Brazilian society, further evidence is needed to establish causation and clarify the mechanisms at play. Still, the observed trends reflect broader transformations occurring in contemporary life, and they highlight the urgent need to understand how societies can adapt to change without losing their cultural coherence. These insights are especially vital for shaping cultural policies that strike a balance between embracing innovation and safeguarding community bonds.

References

Abreu, M., & Brasil, E. (2020, August 27). Toward a history of Carnival. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acre fore-9780199366439-e-820

Aldrich, B. W., Goldman, F. P., & Lipman, A. (2004). Urbanization and familism. International Journal of Sociology of the Family. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23027036

Caldeira, T. P. R. (2015). Social movements, cultural production, and protests: São Paulo’s shifting political landscape. Current Anthropology, 56(S11), S126–S136. https://doi.org/10.1086/681927

Chauvin, J. P., Glaeser, E., Ma, Y ., & Tobio, K. (2016). What is different about urbanization in rich and poor countries? Cities in Brazil, China, India and the United States. NBER Working Paper No. 22002. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w22002

Dessen, M. A., & Torres, C. V . (2011). Family and socialization factors in Brazil: An overview. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 6(3). https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/orpc/vol6/iss3/2/

Duarte, R. (2022). The culture industry in Brazil: From the “classic” model to the digital media. Brazilian Research and Studies Journal, 1(1). https://journal.bras-center.com/bras-j/article/view/3

Fix, M., & Arantes, P. F. (2021). On urban studies in Brazil: The favela, uneven urbanisation and beyond. Urban Studies, 58(4), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098021993360

Gomes, S., Pereira, G. M. L., & Chagas, C. L. (2025). The impact of globalization on changes in cultural aspects. New Science Journal of Social Science, 2(2), 1–10. https://periodicos.newsciencepubl.com/arace/article/download/4299/6291/18045

Hauge, G. M. H., & Magnusson, M. T. (2011). Globalization in Brazil: How has globalization affected the economic, political and social conditions in Brazil? (Master’s thesis, Copenhagen Business School). https://research.cbs.dk/files/58430566/gina_marie_helland_hauge_og_marie_therese_magnusson .pdf

Kelly, J. (2020). The city sprouted: The rise of Brasília. Columbia University Academic Commons. https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/d8-4s5w-ry93/download

La Rosa, T. (2013). Cultural behavior in post-urbanized Brazil: The cordial man (Master’s thesis, Portland State University). https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1666&context=open_access_etds

Maldonado-Mariscal, K. (2020). Social change in Brazil through innovations and educational change. SAGE Open, 10(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020916332

Martine, G. (2010). Brazil’s early urban transition: What can it teach urbanizing countries? International Institute for Environment and Development. https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/10585IIED.pdf

Perlman, J. E. (2007). Globalization and the urban poor. EconStor. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/63592/1/558988636.pdf

Pardo, I., Willaarts, B. A., & De La Mora, G. (2012). Urbanization, socio-economic changes and population growth in Brazil: Dietary shifts and environmental implications. International Union for the Scientific Study of Population. https://iussp.org/sites/default/files/event_call_for_papers/IUSSP%20Willaarts%2C%20Pardo%2 0y%20de%20la%20Mora.pdf

Regis, A. M. de S., Gomes, S. C., & Georges, M. R. R. (2025). The impact of digitalization and technological human capital on the performance of the Brazilian PYME: An empirical study. Journal of Technology Management and Innovation, 20(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-27242025000100074

Salas-Guerra, C. R. (2021). Skills-based on technological knowledge in the digital economy activity. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.01711

Seto, K. S. (2025). Emerging collective actions in Brazil’s tech community. ScienceOpen. https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.13169%2Fworkorgalaboglob.19.1.0050

Silva, D. M. (2022). Digital activism and democratic culture: Can digital political participation strengthen democratic culture in São Paulo? Brazilian Political Science Review, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1590/1981-3821202200010004

Stuenkel, O. (2011). Identity and the concept of the West: The case of Brazil and India. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 54(1), 178–195. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-73292011000100011

Wimmer, A., Bonikowski, B., Crabtree, C., Fu, Z., Golder, M., & Tsutsui, K. (2024). Geo-political rivalry and anti-immigrant sentiment: A conjoint experiment in 22 countries. American Political Science Review, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055424000753

“Vai-Vai: Carnival is fashion, history and resistance.” (2024). Journal of Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology, 5(1). https://medcraveonline.com/JTEFT/vai-vai-carnival-is-fashion-history-and-resistance.html

“Carnival crowds.” (2013). SAGE Open, 3(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013475524

“Carnivals, rogues, and heroes: An interpretation of the Brazilian Carnival.” (2024). Journal of Latin American Studies. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X23000012 Appendix Data collected and visualized by the author through a personal survey

About the author

Lilya Elchahal

Lilya Elchahal is a junior at Westminster in Atlanta, where she has been a dedicated student and community leader since transitioning from the Atlanta International School in sixth grade. Raised in Atlanta, Lilya developed a global perspective early on, fostering a deep love for language and cultures. She is fluent in four languages: English, French, Spanish, and Arabic, and has always had a particular passion for Latin America. Her curiosity about the region was sparked in her sophomore-year Spanish class, where studying Latin American culture inspired her to explore Latin American studies. Researching the political and social environments of various countries deeply resonated with her learning style, and now she hopes to pursue this field as a college major.

At Westminster, Lilya is an active participant in academic and extracurricular life. She is the founder of Angels to Angels, a charitable initiative supporting access to education for underprivileged youth globally, and co-founder and co-president of the school’s Mock Trial program. Lilya leads the Women’s Empowerment and Leadership Club, serves as Business and Outreach Lead for the Robotics Team, and is a committed Lead Admissions Ambassador. She also contributes as a section editor for the Bi-Line, Westminster’s student newspaper, and serves on the Student Alumni Council Board.

Beyond school, Lilya is a Presidential Service Award recipient, a John Locke Essay Competition Finalist, and a member of the National Spanish Honors Society. She has also been recognized by the Scholastic Art & Writing Awards. Lilya is passionate about public service and has held internships with various community organizations while continuing to lead service-based and educational projects.