Author: Hana Khedr

Mentor: Dr. Andrew Franks

Needham High School

Abstract

Misogyny is hatred towards women. It involves belittling, harassing, using, objectifying, sexualising, and harming women. Users on seemingly every social media network have been known to demonstrate some sort of misogynistic behavior towards women, and this behavior may perpetuate misogynistic attitudes and behaviors in others. The proposed study is designed to examine whether exposure to misogynistic attitudes online can affect participants’ attitudes regarding gender violence and, if so, whether this effect is stronger for participants who already hold hostile sexist attitudes. The expected results of this study may help explain the continued prevalence of misogynistic attitude, victim blaming, and consequently reticence among women to report experiences of rape and sexual assault.

Exposure to misogyny is expected to affect attitudes towards gender violence among individuals with high levels of implicit sexism

Increase of accessibility to dangerous ideas and misogynistic behavior online is leading to increased radical criminalization and violence against women. Exposure to and participation in online extremist groups has been a motivating factor in many recent acts of extreme acts of violence such as the racially motivated attack in Buffalo, New York, which was streamed live on Twitch to other users who shared the shooter’s hateful beliefs. While much of the focus of examining hate groups, extremist organizations, and informal forums devoted to spreading hate online has been devoted to issues related to race, women are often the targets of vile, sexualized violent rhetoric (e.g., “Gamergate ”) and this online hatred towards women has been shown to have real world consequences (see, Jane, 2016). In the real world, the effects of gender-based violence are apparent in myriad ways: almost one in three—have been subjected to physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence, non-partner sexual violence, or both at least once in their life (30 per cent of women aged 15 and older). More than 640 million women aged 15 and older have been subjected to intimate partner violence (26 per cent of women aged 15 and older)Of those who have been in a relationship, almost one in four adolescent girls aged 15–19 (24 per cent) have experienced physical and/or sexual violence from an intimate partner or husband.90% of adult rape victims are female. Females ages 16-19 are 4 times more likely than the general population to be victims of rape, attempted rape, or sexual assault. Often, violent crimes against women, even when explicitly motivated by misogyny, are not considered hate crimes despite meeting widely accepted definitions (see, Copeland & Wolfe, 1991). In addition, individuals often are radicalized and emboldened to commit hate crimes and crimes against women–or to perceive such crimes as more acceptable–slowly through incremental exposure to hateful ideas and rhetoric (Soral et al., 2017). Accordingly, the proposed research seeks to examine whether exposure to misogynistic attitudes online increases sexist attitudes regarding violence towards women (including perceptions that such crimes should be considered hate crimes), particularly for individuals with pre-existing implicit misogyny.

Sexism & Violence Against Women

Prior research has indicated that individuals higher in hostile sexism–a belief that women seek to control and dominate men (Glick & Fiske, 1996)–are both more likely to be verbally aggressive toward their own partners (Martinez-Pecino & Duran, 2016) and more accepting of intimate partner violence committed by others (e.g., Yamawaki, et al., 2009). Further, Cross and colleagues (2017) found that, under certain conditions, men who more strongly endorsed hostile sexism were more aggressive toward their female partners during couples’ daily life (Study 1) and conflict discussions (Study 2). International studies have demonstrated that cultures promoting more traditional gender roles also promote higher levels of hostile sexism, which leads people living in those cultures to be more likely to blame women for their own sexual victimization (Hill & Marshall, 2018). Victim blaming is when targets of sexual violence have their own character, motives, and prior behavior scrutinized, and is related to rape myth acceptance, which is a set of beliefs that minimize harm to the victim and attempts to diminish perpetrator responsibility (e.g., Chapleau et al. 2007). High levels of hostile sexism among men are associated with victim-blaming and approval of the aggressor’s behavior (Koepke et al. 2014). Other studies have additionally shown that sexist attitudes are related to a belief that victims of sexual and gender violence “deserved” it (Valor-Segura, 2013; Moya, 2013). Sexist attitudes do not always have to be explicit. Ferrer-Perez and colleagues (2020) expressed concern that traditional measures of sexism are subject to socially desirable response biases (i.e., many people do not want to admit that they hold sexist attitudes). Based on the original Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald & Banaji, 1998), they developed the Gender Violence Implicit Association Test (GVIAT) to measure such attitudes in a way that is less prone to faking and found that the measure predicts outcomes related to gender violence.

The Effects of Exposure to Sexism

Prior research has demonstrated that exposure to sexist images in advertising increases acceptance of sexual assault (Reichl, et al. 2018). Exposure to sexism has also been shown to increase sexist behavior among men in ostensibly real interactions with women (Rudman & Borgida, 1995). Many studies have demonstrated that proliferation of and exposure to sexist attitudes is rampant online (e.g., Fox & Tang, 2014; Shaw, 2014). Germane to the topic of sexual harassment of women online, prior research has demonstrated that anonymity promotes higher levels of sexism on social media through interactive media effects, and such sexism is amplified both via retweets and (even moreso) through writing of new tweets. (Sundar et al., 2015). Such findings indicate that many levels of interactivity may have important implications for the effects of messages sent through online outlets.

Further, exposure to sexist humor leads to increased tolerance of sexism for men high in hostile sexism. Men that are high in hostile sexism have an easy time perceiving sexism as the “norm”. These results indicate that interacting with sexist comments and content online can lead to sexist attitudes offline as well as it is normalized. The fact that the effects of exposure to sexist humor were stronger for participants who were already high in sexism and misogyny is highly relevant to the current study (Ford, 2000). Finally, in a study focused on prejudice more broadly, Newman and colleagues (2019) argued that hate speech should have an ‘emboldening effect’ among the prejudiced. They tested this argument by focusing on the case of the Trump presidential campaign in 2016 and found that prejudiced speech, especially when it is spoken by elite group members and allowed by other elite group members, encourages followers to share and act on their prejudices. These findings are also highly relevant to the hypotheses of the current proposed study.

Hypothesis

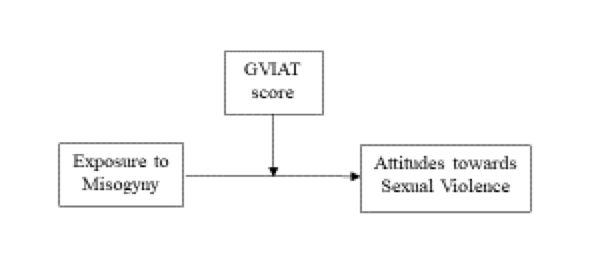

Based on the relevant prior research, I expect that individuals who are exposed to misogynistic attitudes will be more likely to express sexist attitudes regarding violence against women, and this relationship will be moderated by an individuals implicit attitudes towards gender violence. In particular, we expect participants with more positive implicit attitudes regarding gender violence to report less condemnation of sexual violence after being exposed to misogynistic attitudes online.

Method

Participants

Participants will be recruited from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk online workforce and paid $1 USD to complete an experiment hosted on Qualtrics. Participants will report their age, gender, race, income, and education level.

Measures

Implicit Attitudes towards gender violence. The GVIAT is is the most common procedure used, providing a predictive rational compared to explicit measures for socially sensitive topics. In this context, the overall objective of my research project is to provide multi-method measures (explicit and implicit) of misogynistic attitudes and violence against women. The GVIAT operates by categorizing certain words and images into two different categories. In an attempt to overcome the limitations of direct measures, attitudes can be measured through reaction times (RT) (Blair, Dasgupta, & Glaser, 2015). One of the best researched implicit tests is the IAT. The IAT is an indirect measure used to assess the relative strength of cognitive associations between two target concepts and an evaluative measurment by utilizing a number of response discrimination tasks (Fazio & Olson, 2003; Greenwald et al., 1998). The IAT measures the strength of these associations (implicit attitudes) by comparing response reactions to different pairings of the concepts of interest with target stimuli. The preferences of the individual are inferred from the speed of responding to stimuli in a categorization task (Blair et al., 2015; Greenwald, Nosek, & Banaji, 2003). The GV-IAT consists of asking participants to classify target stimuli, presented in the center of a computer screen, into two response categories, Each of these categories are located on either side of the screen, and is represented by two different concepts. Participants have to press a computer key (left or right) as quickly as possible to classify the word in the center (target stimuli) into one of the two categories located on the sides, creating compatible and incompatible pairings. The concepts of the target category are Gender violence vs. Non gender violence and the concepts of the attribute category are Good vs. Bad. Participants will complete a misogyny IAT in which four types of stimuli will be used: pictures of womens, pictures of men, words with negative connotations (e.g., “bad”), and words with positive connotations (e.g. “good”). At the beginning of the task, participants will be told to hit the “e” key if either one type of face (e.g.,women) or one type of word (e.g., positive words) appear and to hit the “i” key if either of the other types of stimuli appear. During the task, stimuli will appear in the center of the screen one at a time, and the participants will need to respond by hitting the correct key as quickly as possible. The computer program will automatically measure the response time and whether the response was correct. Halfway through the task, the pairs will switch. For instance, if the participant was first asked to pair women’s faces with positive words and men faces with negative words, they will now switch to pairs women/negative and men/positive. The computer program will calculate the difference in speed and accuracy for the trials when women faces were paired with positive words and the trials when men faces were paired with negative words. A score of 0 will indicate no misogynistic behavior, while a negative score will indicate high misogynistic behavior.

Exposure to misogynistic attitudes. Exposure to misogynistic attitudes will be an experimental variable where by participants will be randomly assigned to either, a) read a mock Reddit forum regarding gender violence where in no sexist or misogynistic attitudes are expressed, or b) read a mock Reddit forum regarding gender violence where in sexist and misogynistic attitudes are expressed. The full text of the conversations for each condition can be found in Appendix A.

Explicit attitudes regarding sexual violence. The dependent measure will consist of a series of three items measuring different aspects of the participants’ attitudes regarding violence against women. Each item will be responded to on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale. The three aspects regarding violence against women that will be addressed by the items are 1) belief that crimes motivated by misogyny should be considered hate crimes, 2) belief that sexual crimes against women should be considered as severe as murder offenses, 3) belief that many victims of sexual assault are somewhat responsible for being targeted (victim blaming; reverse coded). Full text of items can be found in Appendix B.

Procedure

When first accessing the survey, participants will complete an informed consent document. Participants will then read one of the two Reddit forums containing either non sexist/ misogynistic attitudes v.s sexist/misogynistic attitudes, and respond to attention check items to ensure that they paid attention to what they were reading. Next, participants will complete the measures of sexist attitudes regarding violence towards women. Shortly after, participants will be asked to complete a GVIAT, which will test. Finally, participants will complete measures of demographic and personal characteristics, read a debriefing statement regarding the purpose of the study, and generate a survey completion code to submit on mTurk.

The Gender Violence Implicit Association Test will be used to measure misogyny. Misogyny will be measured on a GVIAT scale. Participants will complete a misogyny IAT in which four types of stimuli will be used: pictures of womens, pictures of men, words with negative connotations (e.g., “bad”), and words with positive connotations (e.g. “good”). At the beginning of the task, participants will be told to hit the “e” key if either one type of face (e.g.,women) or one type of word (e.g., positive words) appear and to hit the “i” key if either of the other types of stimuli appear. During the task, stimuli will appear in the center of the screen one at a time, and the participants will need to respond by hitting the correct key as quickly as possible. The computer program will automatically measure the response time and whether the response was correct. Halfway through the task, the pairs will switch. For instance, if the participant was first asked to pair women’s faces with positive words and men faces with negative words, they will now switch to pairs women/negative and men/positive. The computer program will calculate the difference in speed and accuracy for the trials when women faces were paired with positive words and the trials when men faces were paired with negative words. A score of 0 will indicate no misogynistic behavior, while a negative score will indicate high misogynistic behavior.

Results

Moderation Analysis

Moderation analyses will be conducted to examine whether the ability of exposure to misogyny online to affect attitudes towards gender violence is conditional on participants’ levels of implicit gender violence sexism. PROCESS (Hayes, 2013) Model 1 will be used to test the moderation hypothesis that exposure to misogynistic hate speech will increase the expression of explicitly misogynistic attitudes in regards to sexual violence against women (e.g victim blaming) more strongly as a participant’s level of implicit gender violence bias increases. A separate analysis will be conducted with each of the three dependent measure items. Within each of three PROCESS models, experimental exposure to misogynistic attitudes will be entered as the primary independent variable (x), participants GVIAT score will be entered as the moderator (w), and each of the 3 items reflecting explicitly misogynistic attitudes in regards to sexual violence against women (e.g victim blaming) will be entered as dependent variables (y). The conceptual model is illustrated in Figure 1.

The current study was designed to test whether participants are okay with sexual and misoginistical violence against women. We expect that participants high in levels of misogynistic behavior will exhibit higher results on the GVIAT. Overall, we expect to be able to conclude that misogynistic behavior has a strong effect on society and the male gender nowadays, as it is prevalent in many aspects of modern society and my research is conducted to experiment and prove that nature.

Implications

The results of this study demonstrate the ubiquity of misogynistic attitudes is likely to be recognized by women and result in reticence to report experiences of rape and sexual assault for fear of victim blaming, which will become increasingly likely as men are exposed to misogynistic attitudes. The exposure of misogynistic attitudes such as those that participants would see in our study may lead to reduced perceptions of the seriousness of sexual violence against women and to decreased support for the full bodily autonomy of women. Such effects could manifest as reduced protections of the victim’s of rape and sexual assault and increasingly regressive laws regarding reproductive rights.

Limitations

The conclusions drawn from this study may be limited by the non-representative convenience sample data. The sample was relatively diverse and representative for a psychology experiment, and the study was well-powered with pre-registered hypotheses, methods, and analyses. However, participants in this study may not have been paying enough attention to the text-based experimental manipulation. It should also be noted that our manipulation may not have been strong enough to demonstrate the full extent of the effects of exposure to misogynistic attitudes on those individuals who are already on the higher scale of misogyny.

Future Directions

Future research should obtain sufficient funding to recruit a large and representative sample. They should also consider increased funding as it could allow them to increase experimental realism to ensure that participants are fully engaged with the experimental manipulation, and lastly , future research should also provide additional exposure to misogynistic attitudes for more accurate results regarding the effects of increasing levels of misogyny.

References

Chapleau, K. M., Oswald, D. L., & Russell, B. L. (2007). How ambivalent sexism toward women and men support rape myth acceptance. Sex Roles, 57(1), 131-136.

Cross, E. J., Overall, N. C., Hammond, M. D., & Fletcher, G. J. O. (2017). When Does Men’s Hostile Sexism Predict Relationship Aggression? The Moderating Role of Partner Commitment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(3), 331–340.

Durante, F., Fiske, S. T., Kervyn, N., Cuddy, A. J., Akande, A., Adetoun, B. E., … & Storari, C. C. (2013). Nations’ income inequality predicts ambivalence in stereotype content: How societies mind the gap. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 726-746.

Fazio, R. H., & Olson, M. A. (2003). Implicit measures in social cognition research: Their meaning and use. Annual review of psychology, 54(1), 297-327.

Ferrer-Perez, V.A., Sánchez-Prada, A., Delgado-Álvarez, C. et al. The Gender Violence – Implicit Association Test to measure attitudes toward intimate partner violence against women. Psicol. Refl. Crít. 33, 27 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-020-00165-6

Fox, J., & Tang, W. Y. (2014). Sexism in online video games: The role of conformity to masculine norms and social dominance orientation. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 314–320.

Fox, J., Cruz, C., & Lee, J. Y. (2015). Perpetuating online sexism offline: Anonymity, interactivity, and the effects of sexist hashtags on social media. Computers in human behavior, 52, 436-442.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512. doi:10.1037/0022-3514. 70.3.491

Ford, T. E., Wentzel, E. R., & Lorion, J. (2001). Effects of exposure to sexist humor on perceptions of normative tolerance of sexism. European Journal of Social Psychology, 31(6), 677-691.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. Journal of personality and social psychology, 74(6), 1464.

Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). ” Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm”: Correction to Greenwald et al.(2003).

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach edn. New York: Guilford Publications, 1, 20.

Hill, S., & Marshall, T. C. (2018). Beliefs about sexual assault in India and Britain are explained by attitudes toward women and hostile sexism. Sex Roles, 79(7), 421-430.

Koehler, D. (2014). The radical online: Individual radicalization processes and the role of the Internet. Journal for Deradicalization, (1), 116-134.

Koepke, Sabrina & Eyssel, Friederike & Bohner, Gerd. (2014). “She deserved it”: Effects of sexism norms, type of violence, and victim’s pre-assault behavior on blame attributions toward female victims and approval of the aggressor’s behavior. Violence Against Women. 20. 446-464. 10.1177/1077801214528581.

Martinez-Pecino, R., & Dura´n, M. (2016). I love you but I cyberbully you: The role of hostile sexism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–4. doi:10.1177/0886260516645817

Newman, B., Merolla, J. L., Shah, S., Lemi, D. C., Collingwood, L., & Ramakrishnan, S. K. (2021). The Trump effect: An experimental investigation of the emboldening effect of racially inflammatory elite communication. British Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 1138-1159.

Oksanen,A. Hawdon,J. Holkeri, E. Näsi, M. & Räsänen,P.(2014), Exposure to Online Hate among Young Social Media Users, in M. Nicole Warehime (ed.) Soul of Society: A Focus on the Lives of Children & Youth (Sociological Studies of Children and Youth, Volume 18) Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 253–273.

Reichl, A. J., Ali, J. I., & Uyeda, K. (2018). Latent sexism in print ads increases acceptance of sexual assault. Sage open, 8(2), 2158244018769755.

Ronke, Ojo. (2019). MISOGYNY AND RAPE RATE.

Shaw, A. (2014). The Internet is full of jerks, because the world is full of jerks: What feminist theory teaches us about the Internet. Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, 11, 273–277

Soral, Wiktor & Bilewicz, Michał & Winiewski, Mikołaj. (2017). Exposure to Hate Speech Increases Prejudice through Desensitization. Aggressive Behavior. 44. 10.1002/ab.21737.

Valor-Segura, I., Expósito, F., & Moya, M. (2011). Victim Blaming and Exoneration of the Perpetrator in Domestic Violence: The Role of Beliefs in a Just World and Ambivalent Sexism. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 14(1), 195-206. doi:10.5209/rev_SJOP.2011.v14.n1.17

Williams, M. L., Burnap, P., Javed, A., Liu, H., & Ozalp, S. (2020). Hate in the machine: Anti-Black and anti-Muslim social media posts as predictors of offline racially and religiously aggravated crime. The British Journal of Criminology, 60(1), 93-117.

Wolfe, L., & Copeland, L. (1994). Violence against women as bias-motivated hate crime: Defining the issues in the USA. Women and violence, 200-13.

Yamawaki, N., Ostenson, J., & Brown, R. C. (2009). The functions of gender role traditionality, ambivalent sexism, injury, and frequency of assault on domestic violence perception: A study between Japanese and American college students. Violence against Women, 15, 1126–1142. doi:10.1177/1077801209340758

About the author

Hana Khedr

Hana is a senior at Needham High school. She loves writing essays and conducting research, especially on topics she is passionate about. Hana is excited to keep pursuing research at college and hopes to get more papers published with her future professors and colleagues. Working on this paper has allowed her to reflect and recognize her strengths and areas of developments when it comes to research based studies and helped Hana develop essential and necessary skills that are required in her future career and in the field of psychology.