Author: Ryan Jung

Mentor: Dr. Hong Pan

Suffield Academy

Abstract

Obesity is often misunderstood as a simple matter of overeating or moving too little. In reality, it’s a deeply rooted physiological condition caused by the breakdown of several key systems in the body. This paper examines the development of obesity through five closely interconnected biological mechanisms: fat storage (adiposity), insulin resistance, energy balance, hunger signaling via leptin, and chronic low-grade inflammation. These systems work together to regulate how we store energy, control appetite, burn calories, and respond to stress. When one system begins to fail, like when fat cells grow too large or the brain stops responding to fullness signals, the others often follow, creating a cycle that makes weight gain easier and weight loss harder. The paper also highlights how prevention needs to go far beyond willpower or dieting. Real solutions come from supporting the body’s natural systems through better sleep, balanced eating, physical activity, stress management, and more. Understanding the biology behind obesity helps us replace blame with empathy and find smarter, more lasting ways to support health.

Key terms

| Term | Definition | Relevance to Research Topic |

| Adiposity | The condition of having an excessive amount of body fat. It can be generalized or localized and is often measured by BMI, waist circumference, or body fat percentage. | Central to understanding obesity-related health risks and their metabolic consequences. |

| Insulin Resistance | A physiological condition in which cells fail to respond effectively to insulin, leading to impaired glucose uptake and elevated blood sugar levels. | A key mechanism linking obesity (especially visceral adiposity) to type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome. |

| Energy Balance | The relationship between energy intake (from food) and energy expenditure (through basal metabolism, activity, and thermogenesis). | Governs weight gain or loss; imbalance leads to adiposity and metabolic disruption. |

| Leptin | A hormone primarily produced by adipose tissue that signals satiety and regulates energy balance by inhibiting hunger. | Plays a crucial role in appetite control and is often dysregulated in individuals with obesity (leptin resistance). |

| Inflammation | A biological response to harmful stimuli, which in chronic form can be associated with obesity and metabolic diseases. | Chronic low-grade inflammation in adipose tissue is a hallmark of obesity-related metabolic dysfunction. |

Introduction

Obesity is not just a personal struggle; it is a public health crisis that affects over 650 million adults and 124 million children worldwide. Traditional narratives have oversimplified its causes, framing obesity as a result of poor choices, lack of exercise, or overeating. However, such views ignore decades of research that reveal a much deeper truth: obesity is a chronic physiological disorder involving multiple, interdependent systems that govern metabolism, hormonal signaling, energy storage, and immune response.

Rather than a purely behavioral issue, obesity reflects a breakdown in metabolic homeostasis, the body’s ability to maintain internal balance in response to changing environments. At its core, obesity is the result of a persistent imbalance between energy intake and expenditure, complicated by the dysregulation of hormones such as insulin and leptin, altered fat cell function, and chronic low-grade inflammation.

This paper explores the physiological mechanisms that cause obesity and the interventions that can help prevent or reverse it. We focus on five interconnected biological systems:

- Adiposity (fat accumulation and behavior of fat tissue)

- Insulin resistance (metabolic inefficiency and hormonal disruption)

- Energy balance (caloric intake vs. expenditure dynamics)

- Leptin resistance (dysfunctional satiety signaling)

- Inflammation (chronic immune activation affecting metabolism)

By understanding how these systems interact, we can move toward more effective, biologically grounded strategies to prevent obesity not only at the individual level, but across public health, clinical, and policy landscapes.

1. Adiposity: The Biology of Fat Storage

Adiposity is the quantity and distribution of fat, and that fat, as active tissue, is capable of storing excess energy in the form of triglycerides and communicating with the brain and immune system through hormones and messengers such as leptin, adiponectin, and resistin, assists in thermoregulation, and contributes to the body’s response to infections. (Neufingerl and Eilander 2021)

It comes in two primary forms: white adipose tissue (WAT), the primary storage type that also secretes hormones to regulate appetite and guide energy balance, and brown adipose tissue (BAT), rich in mitochondria that burns calories to produce heat through thermogenesis. It is more abundant in infants, and in adults is found in small quantities, which can be activated with safe cold exposure or during some physical activity. Immune cells, such as macrophages, release the inflammatory factors TNF-α and IL-6 while protective adiponectin falls below a certain threshold. This is known as the ‘adipose tissue dysfunction’. This phenomenon lowers the insulin signal and increases the risk for metabolic disease. From a pathobiology perspective, the location of fat tissue is important because subcutaneous fat located just under the skin is usually neutral, sometimes even protective, and visceral fat that envelops the liver, pancreas, and intestines is pathologically active and produces and excretes inflammatory factors and free fatty acids bound for the liver via the portal vein. This visceral fat is associated with type 2 diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. These behavioral patterns begin at a young age. For example, by performing daily exercise, teens can decrease their fat stores, which improves the functions of the fat cells. These exercise habits, coupled with the intake of healthy unsaturated fatty acids found 5 in nuts, olive oil, and fatty fish, the avoidance of ultra-processed foods, proper hydration that facilitates the lipolytic response, and the application of safe cooling in daily life to invigorate brown fat, shift the ratio of subcutaneous to visceral fat in the desired direction while maintaining the long-term functionality of the adipose tissue. (Guarino et al. 2023)

2. Insulin Resistance: When Cells Stop Listening

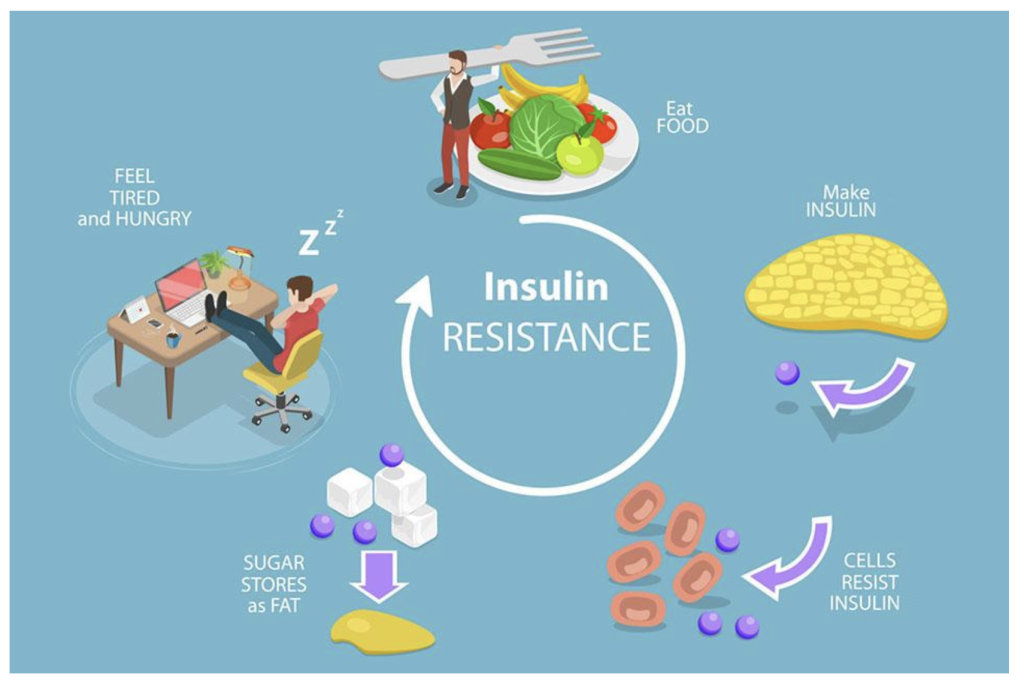

Insulin, which is produced in the pancreas, is a hormone that functions as a ‘key’ that enables the cells in the body to absorb blood sugar. Blood sugar (or glucose) comes from the food we eat, and in particular carbohydrates, which serve as energy for anything from the movement of the muscles to activities done in the brain. When blood glucose is well managed in the body, these cells extract the glucose from the blood and either use it for immediate energy or store it for later use. Save this process, other functioning organs in the body would not get energy, and along with that, blood sugar levels would go uncontrolled.

Insulin is like a key that lets sugar from your food into your cells so they can make energy. With insulin resistance, the locks on the cells get sticky. The key still fits, but the door is hard to open. More sugar stays in your blood, so your pancreas sends out extra insulin to try to force it in. Constantly high insulin, called hyperinsulinemia, makes your body store more fat, especially in your belly, and increases the chance of developing type 2 diabetes over time.

When your body stops responding well to insulin, the effects show up everywhere, because your muscles do not pull in sugar for energy and you feel tired or weak after carb-heavy meals, your liver keeps making sugar even when you do not need it and your blood sugar rises, your fat cells get told by high insulin to store more and belly fat often increases, and your brain’s dopamine system can be thrown off so cravings for sweet or fatty foods get stronger and overeating becomes easier. Early signs include feeling wiped out after eating, 6 getting powerful and frequent cravings for sugary or starchy foods, noticing belly fat that does not budge with normal efforts, and sometimes seeing dark, velvety skin patches on the neck or underarms called acanthosis nigricans.

What drives this problem are habits like eating lots of added sugar and refined grains that spike blood sugar and insulin, long periods of sitting that make muscles worse at using sugar, and ongoing stress that raises cortisol and pushes blood sugar up. What helps most are steady changes such as moving every day with walking, biking, swimming, or strength training so muscles listen to insulin better, cutting back on added sugars and refined carbs while eating more fiber from whole grains, vegetables, beans, and lentils to smooth blood sugar, using a consistent daytime eating window of about ten hours if it suits you so insulin can drop between meals, practicing mindfulness, deep breathing, or yoga to lower stress, and protecting sleep so hormones stay in rhythm. The big idea is simple: insulin resistance is usually a response to a long-term mismatch in food, movement, stress, and sleep, so spotting it early in your teens or early twenties and making steady changes can lower your risk of type 2 diabetes later.

Improved lifestyle habits determine levels of insulin resistance. Diets high in added sugars and refined grains cause blood glucose and insulin levels to spike intermittently, leaving your body with no option other than to “tune out” insulin over time. Prolonged periods of physical inactivity result in the muscular system losing the ability to absorb glucose as blood levels of the sugar increase. Chronic stress also adds insult to injury because of the stress hormone, which elevates blood sugar levels and promotes insulin resistance. The positive news here is that gradual changes work. Exercise most days of the week, including low-impact activities: walking, biking, swimming, and weight lifting, to strengthen the ability of muscle tissues to respond to insulin. Avoid added refined sugars and carbs and consume more whole, plant sources of fiber, including whole grains, vegetables, and legumes, to stabilize blood sugar levels. Time-restricted feeding, or an eating schedule with a shorter time of eating around ten 7 hours, works well for some because it promotes a more sustained drop in insulin between meals. Stress is more effectively managed using mindfulness, breathing exercises, and yoga, and sleep quality must be prioritized in order to regulate hormone levels.

By understanding insulin resistance not as a random malfunction but as the body’s response to a sustained imbalance in diet, activity, and stress, we can take proactive steps to restore metabolic health. Early intervention during adolescence or young adulthood can prevent years of progression toward type 2 diabetes and related conditions, making it a vital focus in obesity prevention efforts. (McGlynn et al. 2022)

Figure 1: Insulin resistance is a type of reaction in a person’s body, especially muscle cells, that makes it less responsive to insulin. By having less reactive insulin within the body, normally it would facilitate the amount of glucose consumed to either store it as an energy source, but since it is getting resisted, the cells do not respond correctly to the insulin signal. This leads to a reduced glucose intake and an increased spike in glucose levels.

3. Energy Balance: The Calorie Equation and Beyond

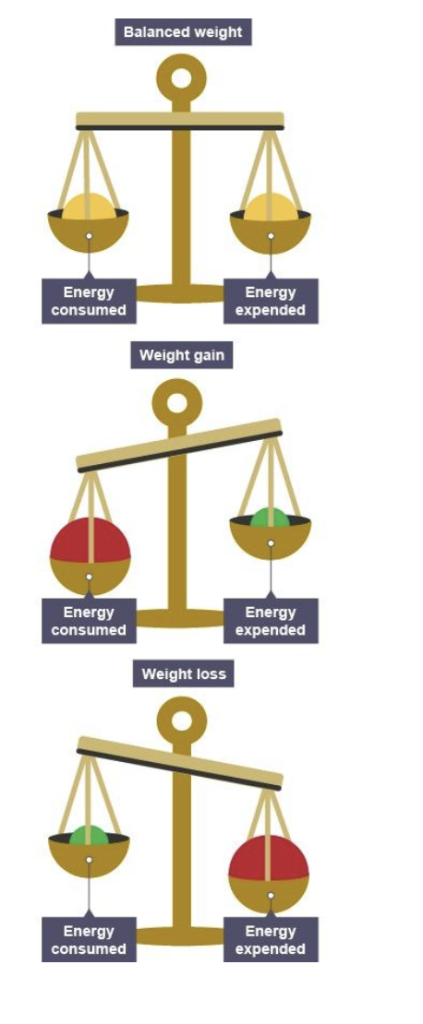

Energy balance is the match between the energy you take in from food and drinks and the energy your body uses for living, moving, and digesting. While it looks like simple math (eat more than you burn to gain, burn more than you eat to lose), your body constantly adapts, so the balance shifts. (Pardo et al. 2021)

Most daily burn comes from basal metabolic rate (BMR), roughly 60–70%, which powers your heart, lungs, brain, and cells even at rest. Physical activity adds a variable share that includes workouts, sports, walking, chores, and small movements like standing and fidgeting (NEAT). Digestion also costs energy via the thermic effect of food (TEF), with protein costing more than carbs or fat. Brown fat can add a small cold-activated boost by turning stored energy into heat. Harsh calorie cuts trigger metabolic adaptation (adaptive thermogenesis) that lowers BMR and, with hormone shifts that raise hunger and reduce fullness, slows loss and promotes regain. Energy imbalance comes in three forms: positive (intake > burn, weight rises), negative (intake < burn, weight falls, but too-large deficits can cause muscle loss, nutrient gaps, and slower metabolism), and neutral (intake ≈ burn, weight holds), and small changes can tip you between them. Long-term balance works best when you support the system rather than obsess over every calorie by building and keeping muscle with resistance training to raise BMR, eating enough protein to protect muscle, increase fullness, and boost TEF, avoiding crash diets that cause large slowdowns, and keeping consistent routines for meals, sleep, and movement. For teens and young adults, habits formed now tend to stick, so favor nutrient-dense foods, daily activity you enjoy, and sustainable patterns, and treat energy balance as a lifelong rhythm rather than a short-term fix to give yourself the best chance at a healthy weight and steady energy. (Kalaitzopoulou et al. 2023)

Figure 2: Energy balance is the amount of calories consumed through food and drink that is equivalent to the amount of calories the body has burned down to equal it out. There are three types of energy balance. A positive energy balance is a state where a person consumes an excessive amount of calories that the body cannot expend. This results in increased adiposity (Obesity) and weight gain. A negative energy balance is the result of taking way too less calories compared to what the body is burning. This will result in weight loss. Lastly, neutral energy balance is the type where the body is equally regulating the amount of calories intake, while the calories are equally burned down. This will lead to weight maintenance.

4. Leptin: The Hunger-Regulating Hormone

Think of leptin as your body’s built-in fuel gauge. It’s a hormone made mostly by your fat cells, and its job is to keep your brain updated on how much energy you have stored. When your body has plenty of fuel, leptin travels through your blood to the hypothalamus, the brain’s control center for hunger, energy, and weight, and delivers a simple message: “We’re good. You can slow down on eating and speed up on burning energy.”

When this system is working as it should, you naturally feel satisfied after eating, your metabolism hums along, and you have the energy and motivation to be active. After a meal, leptin levels rise, telling the brain that your energy needs are met. The brain responds by easing hunger signals and nudging your body to burn a little more. Maybe through movement, maybe through heat production, in a neat feedback loop that helps keep your weight steady without you having to think about it.

When the leptin system breaks, it is called leptin resistance. Leptin levels are high, sometimes very high, but the brain does not “hear” the message. The hunger off-switch feels stuck. Even with plenty of stored energy, the brain acts like fuel is low, so hunger goes up and calorie burn slows down. You can feel hungry soon after eating, and your body holds on to fat. More body fat makes more leptin, which makes the resistance worse, so the cycle repeats. Several forces can throw this system off. Inflammation in the brain, especially in the hypothalamus, can block leptin’s signal. Diets heavy in sugary, ultra-processed, or greasy foods raise oxidative stress, which damages the brain’s appetite pathways. Poor sleep makes it harder too; even one short night can lower leptin, raise ghrelin, and push stronger cravings the next day. Frequent overeating can also numb leptin receptors, the way loud noise can numb hearing.

Leptin affects more than hunger. It interacts with dopamine and serotonin, which shape mood, motivation, and pleasure, so weak leptin signaling can make you feel less driven to move and more likely to eat for comfort. It also affects fertility. If the brain thinks energy is low, it may slow or pause reproductive functions, even when the body has enough fuel. Leptin also links to the thyroid, which sets metabolic speed, so leptin problems often come with a slower metabolism.

The upside is that leptin sensitivity can improve. Getting a solid 8–9 hours of sleep each night helps keep hormone rhythms steady. Regular movement, especially strength training and cardio, reduces brain inflammation and helps leptin signals get through. Omega-3 fats from foods like salmon, walnuts, and flaxseed can also help calm brain inflammation. And avoiding constant snacking, particularly on processed foods, lets leptin rise and fall naturally so your brain has a chance to “hear” it again. (Besci et al. 2023)

Figure 3: Leptin is a peptide hormone made mainly by fat cells, and its blood level reflects total fat stores. Its primary role is to signal the hypothalamus that energy is sufficient, which reduces appetite, adjusts energy expenditure and sympathetic tone, and helps coordinate reproductive, thyroid, and immune functions. In common obesity, leptin levels are high but signaling is blunted (“leptin resistance”), so added leptin seldom causes weight loss, whereas replacement helps in true deficiency and some lipodystrophies. (Kamal-Rahmouni et al. 2002)

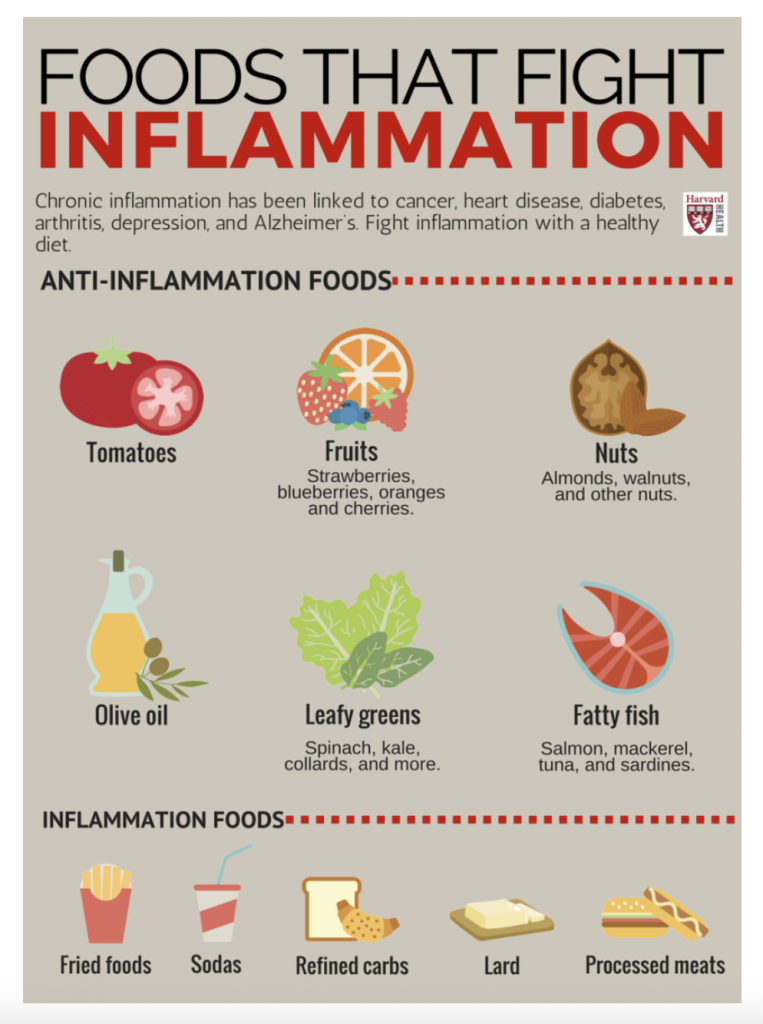

5. Inflammation: The Immune System’s Double-Edged Sword

Inflammation is the body’s built-in alarm system. It’s there to protect us when something goes wrong, like when you cut your finger, catch a cold, or sprain your ankle. In those moments, your immune system sends in its “first responders.” The area becomes red, warm, and swollen because immune cells are flooding in to fight off germs, clear away damage, and start the healing process. Once the job is done, the alarm switches off and your body goes back to normal. That’s acute inflammation, and it’s a good thing.

However, sometimes the body’s alarm does not shut off; it stays low and constant for weeks or years, which is called chronic low-grade inflammation, and it quietly damages tissues over time. In obesity, it often starts in fat tissue, where overgrown fat cells get stressed and send out distress signals that call in immune cells called macrophages; these cells release inflammatory chemicals such as TNF-alpha and IL-6 that make cells ignore insulin and handle sugar poorly, and blood tests often show higher C-reactive protein (CRP), a sign that inflammation is active across the body. This slow fire spreads: in the gut it can weaken the lining and let harmful bacteria slip into the bloodstream (leaky gut), in the brain it can disturb the hypothalamus so hunger and fullness signals break down and leptin resistance develops, in the liver it pushes fat buildup that can lead to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and in blood vessels it speeds plaque growth, which raises the risk of heart attack and stroke.

What you eat, how much you move, and how you handle stress can all influence inflammation. Diets full of sugary drinks, processed meats, fried foods, and packaged snacks make it worse by increasing oxidative stress, a kind of cellular “rusting” that triggers inflammation. Not moving enough is another problem, because muscles release special anti-inflammatory chemicals when you exercise. High stress levels keep the hormone cortisol elevated, which in turn can push inflammation higher. And when you don’t sleep well, your immune system loses its rhythm, tipping the balance toward more inflammation. (Nagorcka-Smith et al. 2022)

The good news is that you can turn the alarm back down. Eating more anti-inflammatory foods, like berries, leafy greens, olive oil, and fatty fish, gives your body nutrients that help calm the immune system. Fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, or kimchi can feed healthy gut bacteria, which in turn protect against inflammation. Moving your body regularly, even just a brisk 20-minute walk, helps your muscles release anti-inflammatory signals. Learning to manage stress through things like meditation, deep breathing, or simply taking time to relax can lower cortisol levels. And making sleep a priority, aiming for 8 to 9 hours most nights, gives your immune system the time it needs to reset. (Nikooyeh and Neyestani et al. 2021)

Figure 4: In nutrition, inflammation is the body’s immune signaling state as affected by diet and body fat. Acute inflammation helps repair, but chronic low-grade inflammation arises with energy excess and poor food quality, raising markers like hs-CRP, IL-6, and TNF-α and promoting insulin resistance, cardiovascular disease, and fatty liver, while ultra-processed foods, refined carbs, trans fats, and heavy alcohol push inflammation up and whole-food patterns rich in vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, nuts, olive oil, omega-3 fish, and fiber that feeds the gut microbiome tend to bring it down, with weight control, regular activity, sleep, and stress management strengthening the effect.

The Cycle: How All Five Systems Work Together

Obesity isn’t caused by one thing; it’s caused by many things going wrong at once:

| System | Problem | Result |

| Adiposity | Fat cells expand and swell | Starts the inflammation cycle |

| Insulin Resistance | Sugar can’t get into cells | Increases hunger and fat storage |

| Energy Balance | Metabolism slows down | Makes weight loss harder |

| Leptin Resistance | The brain ignores fullness signals | Leads to overeating |

| Inflammation | Immune system on high alert | Worsens all other problems |

These problems feed into each other, making it harder to break the cycle. But the good news is: small changes can help reset the system.

Prevention

You don’t need to be perfect. But supporting your body’s natural systems goes a long way in keeping obesity away.

To support metabolic flexibility, try intermittent fasting to improve insulin and leptin and vary your calorie intake across days through caloric cycling, and if you are under 18 or have a medical condition consult a clinician before fasting; eat anti-inflammatory foods by prioritizing whole, unprocessed meals, colorful fruits and vegetables, and healthy fats such as nuts, seeds, olive oil, and fatty fish instead of fried foods; manage stress with short daily meditation, breathing exercises, or yoga and by journaling or talking with a friend, since chronic stress raises cortisol and can promote belly fat; and align with your body’s clock by eating during daylight hours, sleeping at night, and keeping a consistent bedtime because your hormones follow a daily rhythm that works best on a regular schedule.

Conclusion

Obesity is not a simple choice. It’s not a result of laziness or weakness. It’s a physiological condition caused by complex changes in the body’s systems, especially the way fat is stored, sugar is used, hormones are regulated, and the immune system responds to stress. But that also means obesity can be prevented. Not just with willpower, but with knowledge, consistency, and self-care. When we understand how the body works, we can give it what it needs to function better. Instead of focusing only on weight, we should focus on balance between eating and moving, between sleeping and waking, between stress and rest. That’s the key to helping your body feel strong, energized, and healthy.

References

Besci, Özge, Sevde Nur Fırat, Samim Özen, Semra Çetinkaya, Leyla Akın, Yılmaz Kör, Zafer Pekkolay, Şervan Özalkak, Elif Özsu, Şenay Savaş Erdeve, Şükran Poyrazoğlu, Merih Berberoğlu, Murat Aydın, Tülay Omma, Barış Akıncı, Korcan Demir, and Elif Arioglu Oral. 2023. “A National Multicenter Study of Leptin and Leptin Receptor Deficiency and Systematic Review. ” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 108(9):2371–88. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgad099.

Guarino, Miriana, Lorena Matonti, Francesco Chiarelli, and Annalisa Blasetti. 2023. “Primary Prevention Programs for Childhood Obesity: Are They Cost-Effective?” Italian Journal of Pediatrics 49(1):28. doi:10.1186/s13052-023-01424-9. 17

Kalaitzopoulou, Ioustini, Xenophon Theodoridis, Evangelia Kotzakioulafi, Kleo Evripidou, and Michail Chourdakis. 2023. “The Effectiveness of a Low Glycemic Index/Load Diet on Cardiometabolic, Glucometabolic, and Anthropometric Indices in Children with Overweight or Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. ” Children 10(9):1481. doi:10.3390/children10091481.

McGlynn, Néma D., Tauseef Ahmad Khan, Lily Wang, Roselyn Zhang, Laura Chiavaroli, Fei Au-Yeung, Jennifer J. Lee, Jarvis C. Noronha, Elena M. Comelli, Sonia Blanco Mejia, Amna Ahmed, Vasanti S. Malik, James O. Hill, Lawrence A. Leiter, Arnav Agarwal, Per B. Jeppesen, Dario Rahelić, Hana Kahleová, Jordi Salas-Salvadó, Cyril W. C. Kendall, and John L. Sievenpiper. 2022. “Association of Low- and No-Calorie Sweetened Beverages as a Replacement for Sugar-Sweetened Beverages With Body Weight and Cardiometabolic Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. ” JAMA Network Open 5(3):e222092. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.2092.

Nagorcka-Smith, Phoebe, Kristy A. Bolton, Jennifer Dam, Melanie Nichols, Laura Alston, Michael Johnstone, and Steven Allender. 2022. “The Impact of Coalition Characteristics on Outcomes in Community-Based Initiatives Targeting the Social Determinants of Health: A Systematic Review. ” BMC Public Health 22(1):1358. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13678-9.

Neufingerl, Nicole, and Ans Eilander. 2021. “Nutrient Intake and Status in Adults Consuming Plant-Based Diets Compared to Meat-Eaters: A Systematic Review. ” Nutrients 14(1):29. doi:10.3390/nu14010029.

Nikooyeh, Bahareh, and Tirang R. Neyestani. 2021. “Effectiveness of Various Methods of Home Fortification in Under-5 Children: Where They Work, Where They Do Not. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. ” Nutrition Reviews 79(4):445–61. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuaa087.

Pardo, Marta R., Elena Garicano Vilar, Ismael San Mauro Martín, and María Alicia Camina Martín. 2021. “Bioavailability of Magnesium Food Supplements: A Systematic Review. ” Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 89:111294. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2021.111294.

The author utilized an artificial intelligence tool, Google Gemini, and Perplexity to enhance the clarity and readability of the writing. All final content, critical interpretation, and responsibility for accuracy remain solely with the author.

About the author

Ryan Jung

Ryan is currently a junior attending school in Suffield, Connecticut.