Author: Nimeesha Kolari & Radha Panse

Cupertino High School

Abstract

Muscle fatigue is a critical physiological condition that limits physical performance and impacts overall health. While commonly experienced during intense activity, the chemical processes driving fatigue are often overlooked. This paper explores the molecular mechanisms underlying muscular exhaustion, including neurotransmitter imbalances, disruptions in energy metabolism, and calcium regulation failures. By examining the complex processes that result in muscle fatigue, such as glycolysis, byproduct accumulation, and E-C coupling, this paper highlights how biochemical changes affect muscle function. Additionally, strategies such as buffering with sodium bicarbonate to delay fatigue offer insight into potential solutions, thereby enhancing performance. This review first outlines the biological processes that affect muscle fatigue before diving into the deeper chemical aspects of it.

Keywords: fatigue, glycolysis, lactic acid, muscle exhaustion, anaerobic, sodium bicarbonate buffers, E-C coupling, calcium regulation

Introduction

Athletes oftentimes experience severe soreness and slow recovery following a high intensity workout, hindering their ability to perform as usual in the following days. The physiological context of this phenomenon, known as muscle fatigue, was first researched by Angelo Mosso in the late 1800s, who demonstrated how while exercise increases endurance and muscular strength, it simultaneously extends fatigue. He was the first to describe the chemical process behind this fatigue, attributing it to toxic substances and acid. In 1891, he eventually published the paper “La Fatica” (Fatigue), which included a formulation of laws that described the causes of exhaustion. Presently, further research has been established to expand on the cellular and molecular mechanism of muscle fatigue and more specific chemical processes than what Mosso explored over a hundred years ago. Muscle fatigue is now defined as the decline in the body’s ability to produce force, and is known to exist as soreness following physical activity or more critically as a result of a chronic condition.

Fatigue and Hyperthermia

Types of Fatigue Muscle

fatigue results from both central and peripheral mechanisms. Central fatigue originates in the central nervous system (CNS) and occurs when the brain’s ability to send signals to the muscles becomes reduced. Peripheral fatigue, on the other hand, originates within the muscle fibres themselves and reflects impairments within the muscle. Fatigue can also be classified as acute, developing from short term exertion, or chronic, persisting over an extended period due to underlying health conditions. Additionally, hyperthermia, which is a state of increased core body temperature, can worsen both types of fatigue by disrupting homeostatic and neurochemical balances. Key neurotransmitters, including serotonin, dopamine, glutamate, and GABA, play significant roles in the development of fatigue during physical activity.

Hyperthermia and its Impact on Fatigue

Central Fatigue and Key Neurotransmitters

One of the most important neurotransmitters involved in the process of central fatigue is serotonin. Serotonin levels increase during exercise due to a rise in free tryptophan, an amino acid that forms serotonin. As fat stores are broken down during exercise, free fatty acids displace tryptophan from the protein albumin, allowing more tryptophan to enter the brain. There, it is converted into serotonin. High levels of serotonin are linked to sensations of lethargy and reduced motor function. This occurs when serotonin binds to specific receptors (such as 5-HT1A) that inhibit muscle activation once they are overstimulated.

Dopamine, another key neurotransmitter, works in opposition to serotonin in many ways. Dopamine is responsible for maintaining motivation and alertness, both of which are essential for continued physical performance. It is made from the amino acid tyrosine and supports sustained motor output. When dopamine levels are low, central fatigue is more likely to occur. However, regular physical training can increase dopamine synthesis and receptor activity, improving an individual’s resistance to fatigue over time.

Glutamate, the brain’s primary excitatory neurotransmitter, also contributes to central fatigue. Normally glutamate levels are tightly controlled by transporter proteins such as GLT-1. However, intense exercise can impair the function of these transporters, allowing glutamate to build up on the outside of nerve cells. This can disrupt communication between neurons and potentially lead to neurotoxic effects. Additionally, glutamate plays a role in the production of lactate by brain cells, which helps supply energy. If glutamate is not properly regulated, it can affect both brain signaling and energy metabolism, further promoting fatigue.

GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS. During exercise, GABA levels rise, especially in the sensorimotor cortex. This increase is linked to higher blood lactate levels, suggesting a connection between muscle metabolism and brain chemistry. Elevated GABA activity can reduce the brain’s ability to sustain motor output, leading to the perception of fatigue and a decline in performance.

Peripheral Fatigue

Peripheral fatigue occurs when there are changes inside the muscle that interfere with its ability to contract efficiency. These changes often include the buildup of byproducts like H+ ions, inorganic phosphate, and reactive oxygen species, all of which can reduce the effectiveness of muscle contractions. Metabolic acidosis, caused by a drop in pH, weakens the interactions between actin and myosin, the proteins responsible for muscle contraction. At the same time, depletion of stored energy molecules like ATP and glycogen reduce the muscle’s ability to generate force.

Effect of Hyperthermia on Central and Peripheral Fatigue

Hyperthermia acts as a catalyst that intensifies both central and peripheral fatigue by simultaneously disrupting brain and muscle function. When core body temperature rises above approximately 40°C, brain temperature also increases, which can interfere with the hypothalamus and reduce the brain’s ability to send signals to the muscles. This effect on the CNS becomes especially noticeable during prolonged exercise, leading to a drop in endurance and lower motor unit activation. At the same time, hyperthermia stresses the cardiovascular system, as more blood is sent to the skin to release heat. This reduces the amount of blood and oxygen reaching active muscles, pushing them to rely more on anaerobic metabolism. As a result, lactate and H+ ions build up, resulting in peripheral fatigue. Heat also interferes with energy production in muscle cells, making contractions less effective. Together, these effects cause fatigue to set in faster and more severely, especially in hot environments or during physical exercise.

Energy Depletion: Glycolysis

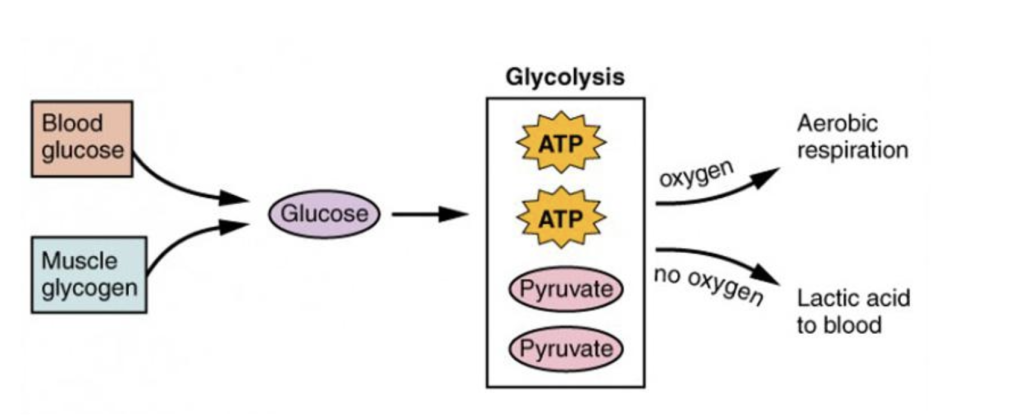

Muscle fatigue is driven by disruptions in ATP availability, particularly when glycolysis becomes the primary energy source during prolonged physical activity. Glycolysis converts glucose to pyruvate, producing ATP rapidly but in limited amounts. As glycogen, the primary substrate for glycolysis, is depleted, ATP synthesis declines, weakening critical energy-dependent processes within the muscle fiber. This process is shown below by Figure 1:

Figure 1: Blood glucose and muscle glycogen provide glucose for glycolysis, producing ATP . With oxygen, pyruvate enters aerobic respiration. Without the presence of oxygen, pyruvate is converted to lactic acid, which enters the bloodstream (Betts et al., 2013)

One of the most affected systems is excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling, which links electrical signals to mechanical contraction. This process relies on ATP to fuel the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+-ATPase, which pumps calcium back into the SR, and for cross-bridge cycling between actin and myosin, the proteins responsible for muscle contraction. Glycogen stored near the SR, particularly in intermyofibrillar regions, plays a key role in sustaining ATP levels. Depletion of this glycogen pool has been shown to reduce SR calcium release, disrupting calcium signaling and weakening muscle contraction even when total cellular ATP is maintained.

Consequences of Anaerobic Metabolism in Muscle Fatigue

Intracellular Acidosis and pH Imbalance

Accumulation of Lactic Acid and H+

Intense exercise results in the body having to make energy without oxygen, leading to the accumulation of lactic acid and hydrogen ions in the muscles. During high intensity exercise, the energy consumption of the body’s skeletal muscle cells increases to compensate for what is released. The majority of this Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) comes from anaerobic metabolism, a process which utilizes the breakdown of glycogen into lactic acid to generate ATP at a quicker rate. The anaerobic glycogen breakdown differs from the normal aerobic pathway due to the lack of oxygen available during the process. Initially, the glycogen goes through glycolysis (see section “Energy Depletion: Glycolysis”), which produces pyruvate and a minimal amount of ATP. Aerobic respiration utilizes oxygen to produce substantial amounts of ATP, as the produced pyruvate moves into the mitochondria and produces CO2, H2O, and ATP. In the anaerobic process, the pyruvate is instead converted to lactic acid (C3H6O3) through the lactate dehydrogenase enzyme. Lactic acid is a colorless compound which exists in two active forms, dextro-lactic acid and levo-lactic acid and can occur in the blood, muscles, or organs.

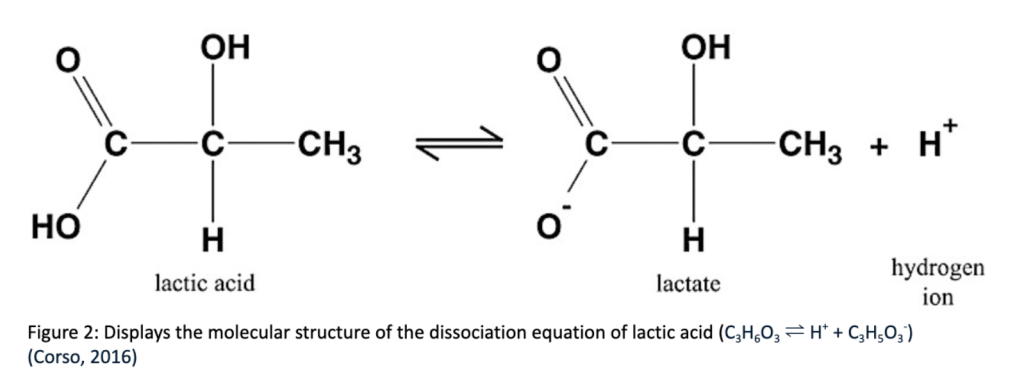

When lactic acid accumulates, it dissociates into lactate and H+ (see Figure 2). The dissociation of lactic acid accumulates H+ , increasing [H+] and therefore reducing pH, as pH is the -log[H+] and is inversely related to the concentration of H+ . The drop in the pH of blood during exercise impairs muscle function and the body’s ability to contract efficiently. In the past, the accumulation of lactic acid was widely considered the main cause of muscle fatigue, but recent studies have attributed the fatigue more to the pH’s effect on the resynthesis of phosphocreatine, rather than a direct effect of the lactic acid.

The Role of Phosphocreatine in Muscle Fatigue

Accumulation of Inorganic Phosphate

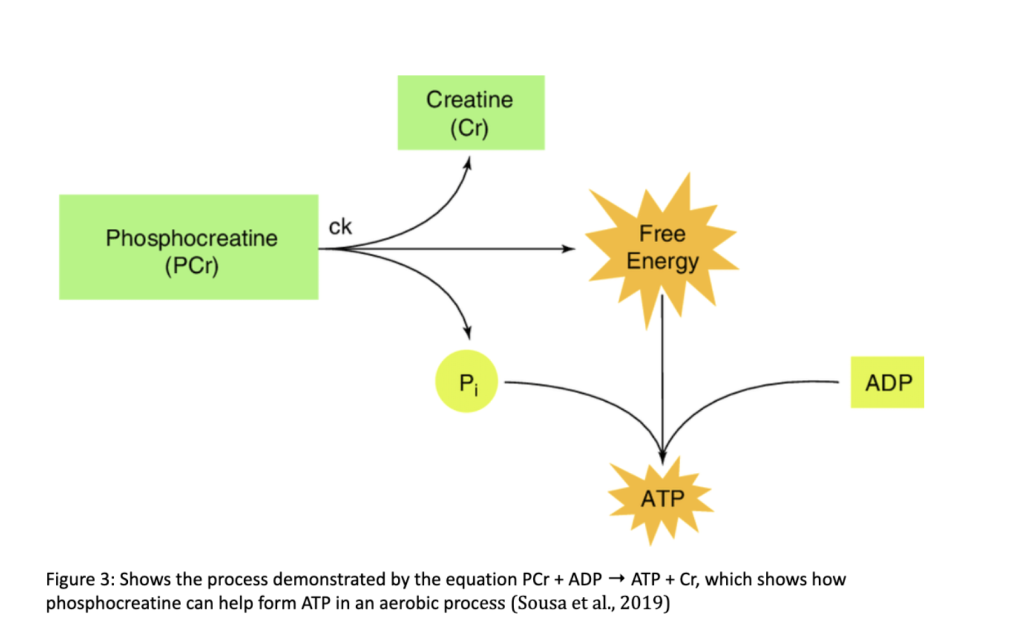

Anaerobic metabolism additionally utilizes phosphocreatine as an anaerobic energy system to speed up the process of ATP generation, as it is able to provide a burst of energy by transferring a phosphate group to ADP (stored energy), forming ATP. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme creatine kinase (CK), and is demonstrated by the image below:

The equation PCr + ADP → ATP + Cr (see Figure 3) displays how the energy that is liberated from the hydrolysis of the phosphocreatine is used to synthesize ATP when the Pi bonds to the ADP. The breakdown of phosphocreatine to inorganic phosphate and creatine can be displayed by the net ionic equation:

PCr → Pi + Cr

The accumulation of inorganic phosphate can depress contractile function and increase muscle fatigue through the formation of calcium phosphate and its effect on our body’s Ca2+ release.

Formation of Calcium Phosphate and Ca2+ Release

The inorganic phosphate formed by the hydrolyzation of phosphocreatine moves from the myoplasm (the cytoplasm of the muscles) to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), a type of reticulum within muscle cells that is responsible for storing and releasing Ca2+ ions and stabilizing calcium ion concentrations. In normal muscle contractions, when muscle fiber is stimulated, the SR releases calcium ions into the cytosol of the cell, allowing the ions to bind to muscle fibers, and triggering muscle contraction. During muscle fatigue, the Pi ions bind to the Ca2+ ions, resulting in the formation of calcium phosphate (CaPi). Due to this, the number of calcium ions available to release reduces, and therefore, the sarcoplasmic reticulum’s ability to efficiently release and uptake Ca2+ is compromised. With a decline in the amount of Ca2+ available for muscle contraction, the body’s ability to generate force is much lower.

Additionally, the decrease in pH in the blood during high intensity exercise (see section “Accumulation of Lactic Acid and pH”) can disrupt the initial process where Ca2+ binds to muscle fibers and triggers contraction in the SR. The surplus of hydrogen ions caused by the accumulation of lactic acid can displace calcium ions from binding sites, where it would otherwise bind with proteins such as troponin C, and allow for normal muscle contraction. The combination of the effect of low pH on the functions of the SR and the effects of the phosphocreatine from the anaerobic process decrease muscle force and power output, resulting in muscle fatigue.

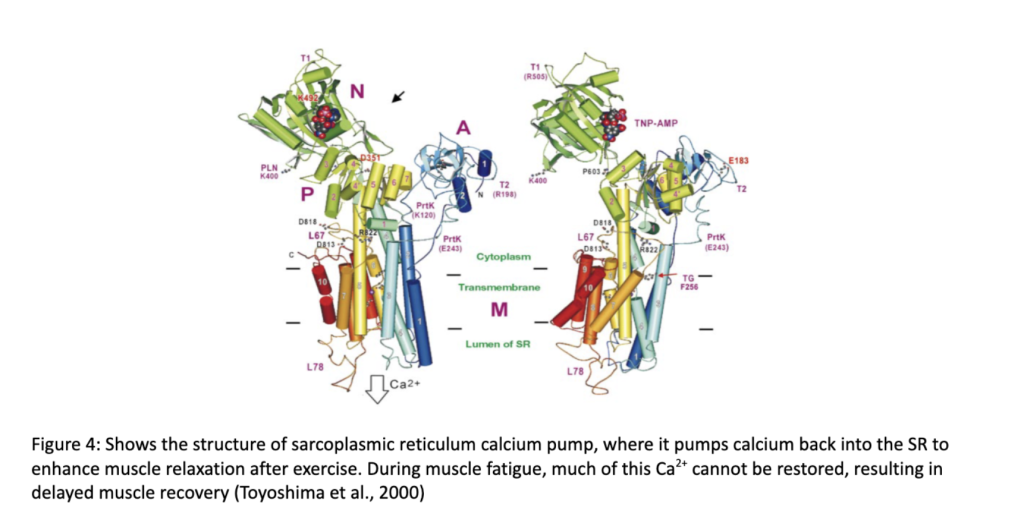

During recovery from high intensity exercise, the sarcoplasmic reticulum uses its Ca2+-ATPase pumps to reabsorb Ca2+ , and ensure relaxation, as shown in Figure 4. Recovery from endurance training, which requires slow-twitch muscles slightly differs from recovery from rapid muscle contractions that require fast-twitch muscle fibers. Due to their higher affinity for calcium transportation, slow-twitch muscle fibers can more efficiently pump Ca2+ back into the SR, allowing for faster recovery from endurance activities than strength or speed work. The difference between recovery for sprint and endurance athletes can be largely attributed to the variation in how their differing muscle fiber types deal with calcium transportation.

Sodium Bicarbonate as a Buffer and its Effect on Athletic Performance

In recent years, some athletes, primarily semi-endurance bikers and runners, have begun a practice of intaking sodium bicarbonate (also referred to as baking soda) with water about 1.5 to 2 hours before their race or competition, with the goal of enhancing their performance. HCO3 – , which is present in sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), is part of the acid-base buffering system present in human bodies that helps regulate blood pH concentrations. The bicarbonate system is the largest buffer system in the blood. When athletes intake sodium bicarbonate, additional reacts with the excess H+ , a process demonstrated by the chemical equation below:

H+ + HCO3 – ⇌ H2CO3 ⇌ H2O + CO2

According to Le Chatelier’s principle and the common ion effect, this shifts the equation to the right and reduces H+ concentration, therefore slightly raising the pH. This further enhances the buffering effect and thus forth delays the decrease in blood pH that occurs as a result of the excess H+ ions. H2CO3 can be defined as a Brønsted-Lowry acid, as it can donate a proton, while HCO3 – , which accepts a proton, can be defined as its conjugate base. A mixture containing an acid and its conjugate base is a buffer and has the ability to resist drastic changes in pH, so by delaying this change, athletes can delay muscle fatigue and slightly improve their performance. As H2CO3 is unstable, it decomposes into H2O and CO2, which is exhaled through the lungs and also helps regulate blood pH. Sodium bicarbonate has also been shown to influence inorganic phosphate creation, again enhancing performance by allowing Ca2+ ions to bind efficiently, even during intense exercise.

Conclusion

Muscle fatigue is not simply the result of overuse, but a result of many chemical processes that often go unnoticed by athletes and many who are struggling from muscular exhaustion. From ATP depletion and lactic acid buildup to pH imbalance, fatigue reflects a breakdown in the body’s ability to maintain muscle contraction at the cellular level. Continued exploration of muscle biochemistry can further practical applications in medicine and sports, and allow for the development of better treatment and training methods for muscle fatigue.

References

Allen, D. G., & Westerblad, H. (2001, November 1). Role of phosphate and calcium stores in muscle fatigue. The Journal of physiology. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2278904/

Calderón, J. C., Bolaños, P., & Caputo, C. (2014, March). The excitation-contraction coupling mechanism in skeletal musclAllen, D. Ge. Biophysical reviews. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5425715/

Constantin-Teodosiu, D., & Constantin, D. (2021, October 27). Molecular mechanisms of muscle fatigue. International journal of molecular sciences. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8584022/

Di Giulio C, Daniele F, Tipton CM. Angelo Mosso and muscular fatigue: 116 years after the first Congress of Physiologists: IUPS commemoration. Adv Physiol Educ. 2006 Jun;30(2):51-7. doi: 10.1152/advan.00041.2005. PMID: 16709733.

Enoka, R. M., & Duchateau, J. (2008). Muscle fatigue: what, why and how it influences muscle function. The Journal of physiology, 586(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139477

Hadzic, M., Eckstein, M. L., & Schugardt, M. (2019, June 1). The impact of sodium bicarbonate on performance in response to exercise duration in athletes: A systematic review. Journal of sports science & medicine. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6544001/

Lactic Acid. (2018). Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 1.

Ørtenblad, N., Westerblad, H., & Nielsen, J. (2013, September 15). Muscle glycogen stores and fatigue. The Journal of physiology. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3784189/

Todd, G., Butler, J. E., Taylor, J. L., & Gandevia, S. C. (2005, March 1). Hyperthermia: A failure of the motor cortex and the muscle. The Journal of physiology. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1665582/

Tornero-Aguilera, J. F., Jimenez-Morcillo, J., Rubio-Zarapuz, A., & Clemente-Suárez, V . J. (2022, March 25). Central and peripheral fatigue in physical exercise explained: A narrative review. International journal of environmental research and public health. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8997532/

Toyoshima, C., Nakasako, M., Nomura, H., & Ogawa, H. (2000). Crystal structure of the calcium pump of sarcoplasmic reticulum at 2.6 A resolution. Nature, 405(6787), 647. https://doi-org.rpa.sccl.org/10.1038/35015017

Westerblad, H., Allen, D. G., & Lännergren, J. (2002). Muscle Fatigue: Lactic Acid or Inorganic Phosphate the Major Cause? Physiology, 17(1), 17–21. https://doi.org/10.1152/physiologyonline.2002.17.1.17

Images

Alger, A. H. (n.d.). 8.3 Phosphagen System (ATP-CP System). Nutrition and Physical Fitness. https://pressbooks.calstate.edu/nutritionandfitness/chapter/8-2-phosphagen-system-atp-cp -system/

Lifetime Fitness and wellness. Muscle Fiber Contraction and Relaxation | Lifetime Fitness and Wellness. (n.d.). https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-fitness/chapter/muscle-fiber-contraction-and-rela xation/

truPhys. (2021, April 12). Lactate… the math, the myth, The legend • truphys. https://truphys.com/lactate-the-math-the-myth-the-legend/

About the author

Nimeesha Kolari & Radha Panse

Nimeesha Kolari and Radha Panse are currently seniors at Cupertino High School in Cupertino, California. Nimeesha is passionate about chemistry in the context of the human body, and is planning to to study biochemistry in college. In her free time, she enjoys running cross country and track, trying new foods with her friends and family, and walking her dogs.

Radha enjoys biology, chemistry, and mathematics, particularly in areas such as biochemistry and pharmaceutical sciences. Outside of academics, she is a member of the school’s track and field team and enjoys exploring nearby trails, building LEGO creations, and reading in her free time.