Author: Akshar Belaguly

Mentor: Tyson Smith

Gretchen Whitney High School

Introduction

“I was neither able to sleep, nor was I able to move out. Many don’t take these medications because of this fear only. ” This was from an unnamed 40-year-old rural male patient from Nagpur, India, who reported adverse drug effects as a barrier for treatment adherence.

“I felt like I was going up and down; I could not sleep the whole night. Taking 12-13 pills was impossible for me… I am already weak, even when you utter my name of taking medicine, my head starts cracking. ”

This was from another rural male patient, but this time 28 years of age, who also mentioned that the side effects were exacerbated due to the quantity of pills and consistency of time required to complete treatment, another key factor as to why long treatment fails.

The above quotes represent rural patients’ experiences with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and its health effects (Deshmukh, Dhande, et. al, 2015). This came from a study between 2012 and 2013, in the Nagpur Drug Resistant TB Centre, a drug resistant tuberculosis center in India, where patients were randomly chosen to describe their feelings after an intensive drug prescription session after they had been diagnosed with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, one of the most dangerous infectious diseases in India right now, if not the most dangerous, according to the CDC as of 2024. Patients have had difficulty adhering to treatments and consistently upholding their regimens due to many reasons; it could all be too much for them and draining their energy or they could have a mental stigma against these medications. All of these will be discussed later in the paper. But first, we must learn more about the disease of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, which is lately causing a lot of problems for patients in India across both urban and rural settings in terms of upheavals of social dynamics and biomedical issues.

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), or rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (RR-TB) is a major, increasingly dangerous, and virulent infectious disease in today ’ s world. Harboring much of the same symptoms of regular tuberculosis, including fever, chest pain, general weakness, cough, and sputum production, MDR-TB is a more dangerous and form of TB, showing large amounts of resistance to major drug classes and products including rifampicin and isoniazid, both commonly used and powerful first-line drugs to treat TB that are now obsolete to treat MDR-TB. This drug resistance is, from the biomedical perspective, caused by increasing numbers of efflux pumps in MDR-TB cells that pump out antibiotic drugs intended to kill the pathogen and more enzymes that inactivate drugs like rifampicin and isoniazid. As a result, the pathogen becomes more potentially fatal considering there are less options for medical professionals to successfully treat the disease as time goes on.

Discovered in 2012 in a Mumbai hospital, the impacts of MDR-TB have gotten worse for a long period of time, mainly explained by the fact that India continues to have 26% of global TB cases as of 2023 (Mandal, Rao, Joshi, et al.). It has become a public health crisis , as this 26% involves 8.2 million people diagnosed with tuberculosis, 1.23 million of those people dying that year.

However, much of the current medical community overlooks the important sociocultural and socioeconomic factors that play a role in exacerbating the MDR-TB situation in India. In culturally-diverse areas with different ways of living and interpreting the world, disparities are bound to occur in terms of medical treatments and how the government and politicians make relevant policies or participate in corruption with regards to MDR-TB regulation and management. These disparities is a main point of focus for medical anthropologists, who use them to explore the historical, sociocultural, socioeconomic, political, economic, and biomedical discrepancies that set the stage for the current crisis of MDR-TB.

The pathogen’ s history of interventions and attempts at treatments, ranging from physical sanatoria to increasing reliance of pharmaceutical drugs after much biomedical research, paints a picture of how global research, beliefs, and actions taken to address tuberculosis has grown over time, especially considering different perspectives and treatment theories that have sprouted throughout history. In addition, socioeconomic disparities, which tend to be highlighted in a densely-populated developing country like India where even an 11.9% poverty rate (as of 2021) is large due to being the most populated nation (as of April 2023), run rampant, consisting of radical differences and discrimination in opportunities for personal and professional development between urban and rural areas (Forbes India, 2024). As will be discussed later, political pressure and corruption is also there to sometimes curb honest data and initiatives being passed, while pharmaceuticalization has grown to be an integral part of India ’ s GDP and overall economic policy.

Integral to the sociological analysis of the TB crisis is the phenomenon of medicalization, a process in which a certain health problem (whether it has to do with psychological, mental, or cultural illnesses) is transformed into a medical problem, where medication and mainstream medicine picks up treatment of this particular illness. In many cases, medicalization can be of benefit to certain sufferers; utilizing prescription drugs and treatments for psychological conditions like schizophrenia and depression has led to success in treating, controlling, and sometimes curing these illnesses. However, most cases of medicalization in other countries (especially developing countries) have actually caused more harm than benefit, often straying the focus away from the ever-important cultural and sociological impacts and influences of disease (Lantz, Goldberg, Gollust, 2023). Therefore, this paper focuses on the classic examples of medicalization in the context of tuberculosis in India, and how that has inadvertently led to its rising drug resistance.

The late sociologist Peter Conrad found that society is now witnessing the “ shifting engines of medicalization, ” explaining how the agents and factors causing medicalization are now shifting away from medical professionals to entities like the pharmaceutical and biotech industries, propelled by consumer demand and commercial influence. The boom in pharmaceutical drugs and treatments via the multiple microbusinesses and private local health practitioners, providing the bulk of Indian healthcare, add further fuel to current medicalization and drug resistance.

This recent emphasis on medicalization also brings forth another aspect into the issue: sociocultural factors. A culturally rich and diverse nation like India harbors multiple cultural beliefs, customs, and practices relating to the health of their various regional populations. Regional cultures, before the arrival of modern medicine and thought, have tended to view disease, especially tuberculosis, in ways that focused more on the social determinants of health rather than the biomedical ones. As we have seen modern medicine and the current global public health system essentially flip the script on this initial approach, community interactions between the old and new will be integral to developing and understanding holistic approaches towards tackling disease.

Historical

Tuberculosis, let alone MDR-TB, has had a long, complex history. Formally discovered in 1882 by Dr. Robert Koch, tuberculosis had been killing “ one in every seven people in the United States and Europe [at the time], ” according to the CDC. However, TB has existed for thousands of years, even showing up in India through ancient medical records and artifacts. During the early 1900s, India largely used sanatoria (isolated medical facilities focusing on good hygiene and care barring antibiotics) to treat tuberculosis, with varying degrees of success. In 1917, the first TB dispensary–a hub for testing and TB treatment–was opened in Bombay, while the first official national study on TB was conducted in 1914 by Arthur Lankester (Central TB Division, 2025 ).

The introduction of allopathic medicine from Europe to colonized nations like India initiated a focus among doctors in India on the biomedical theories and findings of Dr. Koch. Nevertheless, there were a few dissenters who were more keen in delving into alternative theories about the true causes of tuberculosis.

One of these dissenters was David Chowry-Muthu, a T amil Christian doctor specializing in TB. Apart from setting up the first sanatorium hospital in India in 1928, he is also known for challenging the then-largely-accepted bacterial theory of disease causation to instead emphasize the role of environmental factors like poor living conditions and personal well-being in the reduction of illness while avoiding the excessive inclusion of antibiotics. He outlined this stance in his 1921 book Pulmonary Tuberculosis: Its Etiology and Treatment, also proposing reductions in military expenditures to prevent war-related illnesses and investment in urban planning, economic reforms, and improvement in living standards. Even prominent Indian leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru (the first Prime Minister of India) and Mahatma Gandhi (who spearheaded the Indian independence movement), concurred, discussing environmental factors and familial experiences with TB that supported Chowry-Muthu ’ s theory; Nehru used his experience of his wife ’ s struggle with TB to stress the need for more adequate hospital resources while Gandhi emphasized public health and environmental factors like water and air quality, cleanliness, and sanitation as key players in reducing TB’ s spread.

However, Chowry-Muthu ’ s claims could not gain traction mainly due to the Madras Study done in 1950. This study demonstrated that home-based antibiotic treatment was effective in managing TB. It also initiated a rise in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as a gold standard to determine treatment efficacy, leading to more critical views of prior treatment methods.

This larger emphasis on patient autonomy in health and medication decisions synthesized the foundation for the current state of the Indian pharmaceutical industry, which controls the means of production, ownership, and transfer of drugs and treatments for prominent diseases in India. This also includes tuberculosis, and the increasing emphasis on stronger antibiotic drug regimens. It also led to the emergence of the TB Association of India in 1939, and later the National TB Control Programme in 1962-1963 (now the Revised National TB Control Program to address disparities and deficiencies in the original program).

However, this social and medical shift also spelled problems for the control of TB in India. It opened the possibilities for usual patient non-adherence to treatments (due to indiscipline or insufficient resources and education), drug resistance, and major anxiety about the recency of treatments and their efficacies. The initially popular Bacillus-Calmette-Guerin vaccine for TB became ineffective in 1979, while the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in India in 1984 and development of drug resistant strains of TB in 1992 spelled further trouble for those suffering from TB symptoms.These expose the deep sociocultural barriers and disparities present in various Indian communities, which exacerbate the toll TB is taking on the Indian populace with regards to the rampant antimicrobial resistance.

Sociocultural

Arguably the largest factor about the current spread of MDR-TB in India is the influence of sociocultural factors. This is true to a capacity for essentially any disease, but this has been recognized by the current medical community mainly for diseases relating to mental health and wellness, while these same factors that apply to infectious diseases with physical symptoms have been overlooked by much of this mainstream medical community, which tends to focus mostly on the biomedical aspect of these diseases. In the case of tuberculosis, even with all of its physical symptoms like coughing, sputum production, and fatigue, there are extensive cultural habits, beliefs, and practices especially prevalent in India that can be attributed to the exacerbation of certain virulence factors and creating perfect environments for maximum infection and worsening of symptoms.

The rampant medicalization in the modern world, comprised of larger focuses on biomedical aspects without consideration of sociocultural, economic, and other external factors, has led to large cultural shifts in India especially, with more urban participation in biomedical treatment regimens like Direct Observation Therapy, Short-Course (DOTS) being a largely popular treatment option. This treatment option involves regular supervision of TB patients from medical professionals (mainly to ensure treatment adherence) as they take complex doses of specific medications as a multidrug treatment, common among patients whose TB strains have gained resistance. The degree to which these kinds of programs succeed in India vary strongly by unique state funding and political support, but over the years, DOTS has become the main option for a lot of Indian citizens, with over 12 million TB patients using DOTS since the program’ s inception. However, to understand the true sociocultural and anthropological concepts underlying these issues, we need to go over some basic theories.

The concepts of illness and disease, while sounding similar, are defined differently in the medical anthropology field. Illness describes a patient’ s sociocultural experience of disrupted health, characterized by physical symptoms (like a fever or sore throat), or psychological symptoms (like missing out on a vacation with friends), meaning that illnesses are not confined in only the mental, psychological, or physical space. For example, the flu, a disease caused by the influenza virus, portrays these same aspects; an affected individual has physical symptoms like cold and runny nose as well as psychological and mental symptoms like intrinsic feeling of weariness separate from the physical malaise that the flu is known to cause. However, disease is confined to only physical illnesses and biological abnormalities, like a viral infection. It is the illness which can validly have real consequences and effects on both social dynamics and biological health, while the term “disease ” can really only be utilized to describe an ailment with physical symptoms. It is the misuse and misinformation, along with potential for social manipulation, of the definitions of these two terms that set the foundation for the underlying sociological dynamics surrounding India ’ s public health and tuberculosis situation.

Especially in the case of India, social norms and cultural practices often exacerbate and amplify this stigma and these negative social dynamics. In multiple communities, cultural dynamics and disparities continue to alienate TB patients even with current efforts by the government to reduce the incidence of TB. While the government may be dealing with the physical, biological problem of tuberculosis, not much is being done to address its persistent social impacts. Cultural beliefs and practices of citizens

According to a health care providers handbook developed by the Montgomery County Office of Community Partnerships and the Asian Pacific American Advisory Group in Montgomery County, Maryland, multiple considerations into religious, cultural, and ethnic beliefs must be taken in healthcare settings. Some cultural beliefs listed include a steadfast belief in cleanliness and bathing, higher power granted to elders of families for decision-making, occasional reliance on traditional home remedies based in Ayurvedic medicine, and a severe aversion to cow and pig materials due to religious reasons.

Though this pamphlet describes appropriate treatment strategies and ways to approach the health of Hindu patients, this applies fairly well to Indian Hindu citizens due to having the same foundational beliefs, practices, and worldviews (Queensland Health Multicultural Services, 2011). However, whatever is identical in theory may not be identical in social and physical symptoms. Some of these beliefs, including this belief in cleanliness, may not be able to be fully carried out due to inherent vulnerabilities in India surrounding unclean facilities and resources that may make it theoretically impossible to fulfill these things. In many rural communities, taking a bath may constitute bathing and submerging oneself in a holy river or nearby lake, but many of these communities may have unclean water and unsanitary facilities for this activity, resulting in inadvertent bodily contamination in the guise of an important cultural practice and belief in cleanliness.

Ayurvedic medicine, the main native-Indian medical and cultural belief and practice system based on Hindu tenets, is centered around natural materials like herbs, spices, and other plants typically found in South Asian regions, is not a proven legitimate alternative to allopathic medicine, though it shows much promise nonetheless. Due to the uncertainty of value and effectiveness of this medicine, Indian patients, especially older ones, may have a natural preference for Ayurvedic medicine, which could have an impact on the effectiveness of their treatment (if they do ultimately opt for Ayurvedic medicine), or have a psychological impact on the manner in which they utilize allopathic medicine (since they may not fully believe in it).

Most importantly, most Hindu patients view all illnesses as containing a biological, psychological, and spiritual element, often attaching a stigma to mental illness and cognitive dysfunction in particular.

This stigma results in illnesses being considered as karma for misdeeds in a past life, along with the concept of the evil eye (which is usually attributed to being a cause of mental or physical illness). These kinds of stigmas, especially amplified in rural communities, often lead to social ostracization from friend groups and extended families, which can lead to isolation and a real belief of being punished by a religious power.

The nuance doesn’t stop there. While a lack of emphasis on biomedical knowledge could definitely end up badly with social ostracization, medicalization can shake up the entire dynamic. This time, because an illness is related to an actual explainable biological problem, people tend to start avoiding affected individuals and refuse to reach out for social connections or social gathering to help accommodate the individual in the community; essentially, it is an internal exile from society that occurs.

These social conditions and issues are further exacerbated through the specific social dynamics present in care centers and hospitals in both rural and urban India. In fact, doctor-patient dynamics aren’t instrumental to just Indian TB, but to any health condition in any country. And it’ s been mainly due to American medical influence.

For example, Ethan Watters, through his New York Times article The Americanization of Mental Illness, talked about Dr. Sing Lee, a Hong Kong doctor who witnessed the moment when anorexia hit China; before the Western media could describe it, Chinese locals believed that anorexia, like multiple other physical diseases, wasn’t really connected to fat phobia, and not many reports of fat phobia came out initially (Watters, 2010). However, once the local Hong Kong population Western media connected anorexia to fat phobia, the number of reports on fat phobia in Hong Kong skyrocketed (not because there was fat phobia in the first place, but because the perception of individuals ’ health changed due to exertion of social control by the Western media).

This Americanization of illness in general continues to affect Indian tuberculosis, especially through doctor interactions. When an Indian patient visits a doctor from a high-profile medical institute or hospital, the expectation is that prescription medication and biomedical treatments will be given, due to recent Westernization of global medicine. However, the same is not true as to when a patient visits a local clinic or uncertified care provider like a Ayurvedic medicine guru in villages; in this case, patients usually expect local, homely treatments like simple spices, herbs, fruits and vegetables, and more ordinary forms of medicine rather than prescription medication.

The differences don’t stop there. The social dynamics run so deep that even the expectations for quality of care are influenced across backgrounds. Patients may expect allopathic medicine doctors from wealthier, more well-organized areas to be of higher quality, while they may also expect local healers to have less quality health (though they may go to the healer aware of this and ready to take the risk unless they truly believe in alternative forms of medicine). This just goes to show the extent to which the Western world has influenced medicine in India, and it’ s impacting tuberculosis very much.

Often with diseases like tuberculosis, mortality statistics are assumed to be directly related to medical measures and advancements directly taken by national governments to decrease incidence of a particular disease or illness. However, this is not always the case. Around the twentieth century, there was a growing discussion in the scientific community regarding the questionable contribution of medical measures and medical service expansions to a recent decline in mortality rates; this was especially seen with the decline of smallpox in Britain, with people believing that the invention of smallpox inoculation helped eradicate it. While the smallpox inoculation did play a large role in curbing smallpox cases, improvements in environment were also pointed out, mainly by Habakkuk and McKeown, especially focusing on rising standards of living (mainly in diet), hygiene improvements, and a favorable trend in the relationship between microorganisms and their human hosts.

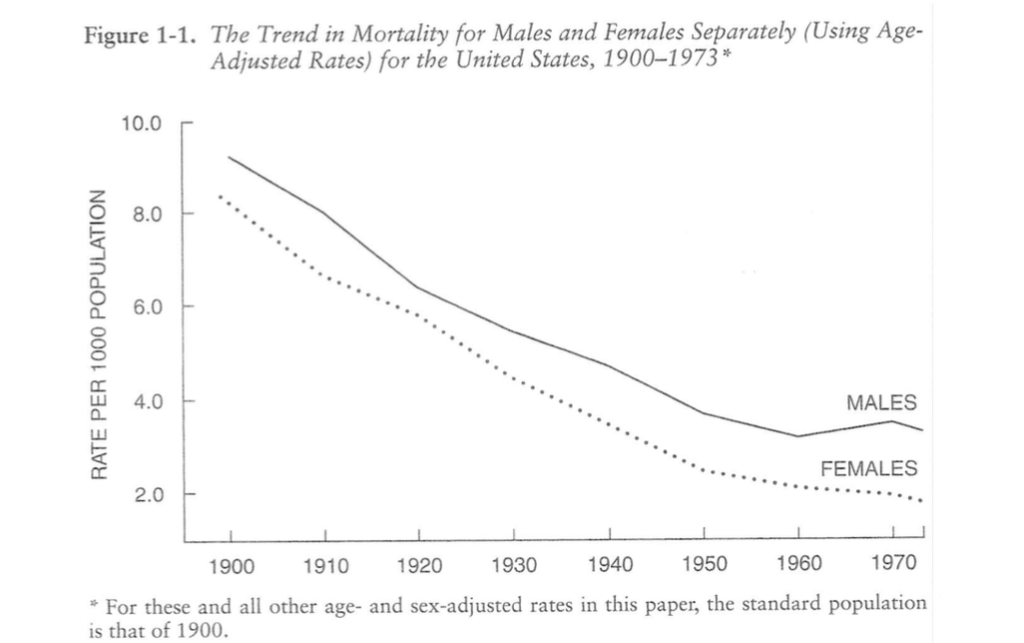

Since 75% of the decline in mortality rates in the 20th century were associated with infectious diseases, there can be three primary influences: medical measures and immunization, reduced exposure, and improved nutrition. In the graph below (citation: McKinlay), this effect has been largely shown between men and women in the US.

Source: Medical Measures and the Decline of Mortality (McKinlay, 2013)

In addition, most of the mortality decline is from a decline in infectious diseases, so medical measures have usually been focused on this instead of other causes of mortality like heart disease, cancer, and other conditions. This further reinforces the fact that medication and biomedical advancements weren’t the chief agents that caused the massive drop in reduction in the 20th century. Especially as can be seen with tuberculosis in the graphs shown below for the nine most common infectious diseases, the first powerful and reliable drug for tuberculosis, isoniazid, came out around 1950, but the mortality rate associated with TB was already decreasing significantly by that time (McKinlay, 2013).

Source: Medical Measures and the Decline of Mortality (McKinlay, 2013)

So because these medical measures contributed little to the overall decline in mortality for the US, this data can be extrapolated and generalized for tuberculosis in India as well. There is, in reality, a much larger emphasis on cultural contexts, practices, and beliefs through this concept than biomedical interventions when it comes to tuberculosis rates in India. Therefore, medicalization, by amplifying the need to focus on the biomedical aspect, is indirectly hurting efforts to control tuberculosis long-term while risking to increase resistance to dangerous levels.

This rampant medicalization in the modern world has led to large cultural shifts in India especially, with more urban participation in biomedical treatment regimens like Direct Observation Therapy, Short-Course (DOTS) being a largely popular treatment option, involving regular supervision of TB patients from medical professionals to ensure treatment adherence. The degree to which these kinds of programs succeed in India vary strongly by unique state funding and political support, but over the years, DOTS has become the main option for a lot of Indian citizens, with over 12 million TB patients using DOTS since the program’ s inception.

DOTS has a lot of social nuances to it. The concept, involving supervision and encouragement from medical professionals to take large, consistent regimens of medication to fight TB (the prescriptions grow larger as TB becomes more resistant), may seem theoretically sound, but practically, it’ s more complicated than that. The main complaint with DOTS has been the social connection between the medical provider and patient. If the medical provider is a distinguished health professional or doctor while the patient is a rural patient, there may not be much trust and connection immediately that may guarantee a consistent adherence to the treatment regimen. However, a local healer facilitating the DOTS process may have much more success due to greater familiarity and connection and trust. This, as will be discussed later, can only be achieved through regulation of the private sector, which has so far been a huge missed opportunity for the Indian government.

Socioeconomic and political economy

Just as there are sociocultural disparities and nuances with the way healthcare resources are utilized for tuberculosis treatment, socioeconomic gaps and political influence reign supreme in determining the way the Indian public health system deals with MDR-TB. However, some major economic drivers and players need to be examined to first get a grasp on the scope of the issue at hand.

As discussed earlier, the newfound citizen medical and health autonomy has come in recent times with a stronger pharmaceutical sector. The Indian pharmaceutical sector is one of the most popular and sought-after markets in the world, and it’ s very easy to see why it’ s called the “Pharmacy of the World” . With over 10,500 manufacturing facilities, this sector, the 3rd largest (by volume) and 14th largest (by value) global provider of generic drugs, is mainly used for aspects of global medicine like affordable vaccines and treatments; this has been so well done that India is known for giving low-cost, high-quality medicines to its citizens and to other countries receiving Indian imports. This cost efficiency and innovation has greatly enhanced India ’ s GDP and improved healthcare outcomes for diseases like tuberculosis.

According to the Indian Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF), as of 2024, the Indian pharmaceutical market was worth 65 billion USD and is expected to reach a valuation of 130 billion USD by 2030 and a valuation of 450 billion USD by 2047. In addition, India has the largest number of USFDA-compliant pharmaceutical plants outside the US, along with over 2,000 World Health Organization Good Manufacturing Practices (WHO-GMP) approved facilities with more than 10,500 facilities in more than 150 countries. These statistics continue to show the sheer dominance, reliability, and influence India holds in the global pharmaceutical market. This ultimately has many effects towards the national economy.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) DataMapper and other recent data from the Indian government, the Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Industry has a large 1.72% contribution to the national GDP (Make in India, 2025). In addition, a trade surplus (meaning more pharmaceutical goods have been exported rather than imported, which increases GDP contribution) has also been maintained since 2010, with an annual trade surplus of about $13.10 billion USD in the 2018-2019 year range. The industry has also received a cumulative FDI (foreign direct investment) of about $16.5 billion USD from April 2000 to March 2020, showing its appeal and potential for further outside investment. Distribution of drugs via the pharmaceutical sector is achieved through multiple health care centers and health-based microbusinesses, mainly prevalent in multiple population-dense areas and making up nearly 30% of India ’ s GDP (Aftab, 2024).

The scope and grandeur of the Indian pharmaceutical industry has so far been conveyed with the above economic statistics and information. However, with a densely populated country like India, problems and socioeconomic disparities are bound to occur with how the pharmaceutical sector transfers and communicates health information and medication to the public, with both urban and rural areas having numerous issues regarding this.

When it comes to the quality of healers, it was already mentioned earlier that perceived higher quality healers, which tend to be more professional healthcare providers from the biomedical sector, are seen more favorably by the expectations of patients than perceived lower quality local healers. In addition to this, as may be obvious, these higher quality healers tend to be more expensive and may be inaccessible to poorer individuals (of which there are many in rural areas), while lower quality healers may be the first choice due to cost efficiency. However, this relationship between quality of care and socioeconomic standing greatly widens the wealth and health gap, as poorer individuals tend to have worse health outcomes with TB than wealthy individuals, all because of class differences between local healers and more high-profile health professionals in relatively large hospitals.

This can also be seen with DOTS, as it was already mentioned earlier that DOTS tends to be more successful if trust and connection is there between patient and health provider; this tends to be truer if a wealthy patient connects with a health professional while a poor patient might connect better with a local healer (again, there will be a difference in quality of care if this occurs, and it may not look good). Therefore, it can be said that higher quality DOTS is more available and viable to individuals in high socioeconomic standing and quality of living, while the opposite is true for lower socioeconomic standing, which may not get proper DOTS treatment from local healers, especially considering the lack of governmental regulation of the private sector of health.

The simple solution to this, one could say, is to meaningfully expand higher quality DOTS care, medication, and health resources to poorer parts of the country. However, an expansion of care, testing units and areas, treatments, and appropriate medical expertise to more rural areas of India while keeping consistency of good quality is incredibly difficult and costly; this is especially true for India, the world’ s most populated nation. Costs for the Central TB Division, the main governmental department dealing with the control and reduction of tuberculosis cases through the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme (NTEP), have risen from $76 million USD from 2016 to nearly $2.5 billion USD, reflecting India ’ s promise to eradicate tuberculosis by 2025, but this still continues to fall short of their goal of a 2.5% GDP budget allocation, though this may change in the coming years. Additionally, the possibility of false data reporting, internal corruption, and underrepresentation among numerous regions threatens to derail these seemingly promising statistics. Just the baseline upscaling, without even factoring in DOTS and medical private sector regulation, is already costly and not meeting its GDP allocation goals so far, showing that if India wants to upscale its TB testing and treatment centers without sacrificing quality, a shift in the baseline system is necessary.

Biomedical/Biological/Biochemical

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB), harboring much of the same symptoms of regular tuberculosis, including fever, chest pain, general weakness, cough, and sputum production, is a more dangerous form of TB, showing large amounts of resistance to major drug classes and products including rifampicin and isoniazid, both commonly used and powerful first-line drugs to treat TB that are now obsolete to treat MDR-TB. This drug resistance, as mentioned earlier in the introduction, is caused by increasing numbers of efflux pumps in MDR-TB cells that pump out antibiotic drugs intended to kill the pathogen and more enzymes that inactivate drugs like rifampicin and isoniazid. As already discussed, patient and sole care-related factors that may exacerbate antimicrobial resistance include inappropriate use of TB drugs and formulations along with premature treatment interruption, causing drug resistance.

Currently, multiple prescription drugs that can treat multidrug-resistant tuberculosis now are in good supply, although the pathogen can threaten these drugs too if resistance goes unchecked into the future. These include second-line drugs like levofloxacin, moxifloxacin (both of which are fluoroquinolones), and combination regimens that include drugs like moxifloxacin, clofazimine, and ethambutol, among others. These combination regimens are commonly used in Direct Observation Therapy Short-Course (earlier described as DOTS), which has had growing global success but still suffers the risk of patient indiscipline and misinformation. This risk, while negligible in the first few decades since antibiotics were introduced to treat tuberculosis due to their great strength, has now become relatively larger, making those same antibiotics powerless against modern infections. Due to this growing resistance, it is imperative for affected nations to focus on widespread access for testing and treatments; in India specifically, as will be discussed in a later section in more detail, the Central TB Division is now hoping to do this.

The actual process of drug resistance is quite complex. Tuberculosis drug resistance occurs when the bacteria that cause TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, develop mutations (or are transferred genetic material from other bacteria with resistance genes) that allow them to survive despite the use of anti-TB drugs. These mutations usually become a problem when treatment is not properly followed, as already discussed. For example, mutations in the katG or inhA genes make the bacteria resistant to isoniazid, while mutations in the rpoB gene cause resistance to rifampin, both of which are the top-line drugs to treat tuberculosis. When the bacteria become resistant to both, the condition is called multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). If resistance extends to second-line drugs like fluoroquinolones or injectables, it is called extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB). If the process goes even further and the TB pathogen somehow becomes resistant to all drugs (meaning it is practically impossible to treat with medication), it is called pan-drug-resistant TB (PDR-TB); while there haven’t been much cases of PDR-TB yet, it still remains a looming fear on the horizon should the global public health system continue to neglect drug resistance.

To combat these threats of multidrug-resistance and extensive drug resistance, global public health systems and the modern medical community are focusing a lot on biomedical treatments like novel drug development, new drug therapies, possible applications of immunotherapy, and more. This emphasis on medical conditions, while important, has also come at the expense of neglecting relevant external issues relating to regional cultures, socioeconomic disparities, and other topics that are listed in this paper. While biomedical treatments have been emphasized (especially in India, where , there has been a relatively lack of concern for these conditions, which may include poor living conditions, unsanitary resources (water, food, air), lack of sanitary protocol in everyday life (for example, lack of handwashing), and even certain cultural practices and beliefs that may inadvertently cause this (as was already discussed in a previous section).

Over time, Indian biomedical treatments themselves have changed in efficacy towards treating TB (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; Govt. of India, 2022). Mass Bacillus-Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine campaigns started in India in 1951, but soon proved ineffective in the 1990s, especially against TB strains in India that had grown more resistant and more strongly attacked the lungs of the victim. Shortly after these campaigns, there was a notable shift towards home-based chemotherapy, employing many of the same drugs that are used today to treat tuberculosis; however, access to these drugs varied in the initial days, and access only got strengthened following the rapid growth of India ’ s pharmaceutical market, which was discussed earlier. The treatments and testing methods for TB, while advanced, are relatively costly and hard to implement; a regular DOTS regimen

As mentioned earlier in the introduction, MDR-TB has proven to be a huge problem over the past few years for the country ’ s public health. The impacts have gotten worse since its discovery in 2012 in a Mumbai hospital, explained by the fact that India continues to have 26% of global TB cases as of 2023 according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). It has become a public health crisis , as this 26% involves 8.2 million people diagnosed with tuberculosis, 1.23 million of those people dying that year (Mandal, Rao, Joshi, 2023).

While this discussion on the biological and social issues and influential factors related to the current case of MDR-TB has been far-reaching, these factors tend to be caused by underlying flaws in global health systems.

Systemic Flaws

A large part of these discrepancies in healthcare, treatment, and true betterment of the afflicted when it comes to MDR-TB in India is due to the underlying public health system of India. There are multiple flaws with the Indian healthcare system when it started to handle the tuberculosis (and later the rising resistance of later strains), and a lot of it has to do with the main government department tasked with controlling the spread of TB: the Central TB Division, carrying out the the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme (formerly called the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme).

The emphasis in this program largely paints MDR-TB as a public problem, which it essentially is. Usually, the government should ideally ensure public action, not necessarily the individuals, but this may need to change in the future, as the public needs help from experts, advocates, pressure groups, and lobbyists to represent their perspectives and interests (which maybe are not being considered by the Central TB Division currently). This conveys that multiple individual actors in Indian society, while having the potential to influence health policies sociopolitically, are usually experiencing a power imbalance, with higher-status actors having more power to influence unlike lower-status actors like the enormous Indian middle class. Systematically speaking, inclusion of all local groups of actors, including public health practitioners, health planners, policy makers, and patients themselves, might seem impractical from a financial and economic standpoint but it is absolutely necessary for this form of equity to show when constructing a public health system.

Additionally, funding tends to gravitate towards the political and medical interests (which tend to be more high-paying and lucrative), which affect the health decisions the Central TB Division takes. This is especially true in defining TB, exerting medical social control over the concept of the disease. This fascinating social dynamic leads to an interesting clash: should we keep the Central TB Division (basically the government) or the vocal actors (that bring in important perspectives, like private practitioners, non-governmental organizations, and researchers) out of the limelight.

Weak data exists for the TB epidemic, as there was a lack of data from the unregulated and diversified private sector (more on this later). When a large TB epidemic sprouted up in 2013, the government took data on a few hospitals in Gujarat and Chennai over the course of a few weeks, hoping to extrapolate and adjust these numbers to represent the whole nation. The data showed 1-3% MDR-TB in Gujarat and Chennai, with 13-17% resistance in previously treated cases. In addition, 3% of TB patients in the Gujarat and Chennai studies are considered to have native MDR-TB (in other words, they had it already when they came into the hospital), while 17% of TB patients were considered to have acquired MDR-TB (meaning they most probably acquired the strain during their hospital stay). This continues to show how drug resistance is especially opportunistic in nosocomial, or hospital-acquired, infections.

Of course, even when assuming that the Central TB Division honestly collected the data as best they could, there are still general epistemological questions to be asked when considering the validity of the data as a whole. For example, mortality statistics may be inadequate; according to sociologist Dr. John B. McKinlay, many conditions may be responsible for deaths (and not just the one that the patient came to the hospital with). In addition, changes in disease classifications and social norms and expectations of health illnesses can also negatively influence these statistics (for example, death by epilepsy might have been perceived as negative spiritual outbursts in an earlier time). However, we should still be able to measure those limitations and hopefully account for them, especially considering these limitations may apply equally to all studies involving mortality stats, especially ones involving TB hospital deaths.

However, critics have a different outlook. Looking at the fishy nature of these numbers and statistics, they feel that the government is not facing up to the problem’ s scope, exaggerating overly optimistic TB data that may give a false sense of security when a 3% nationally-extrapolated rate of MDR-TB, doubting whether the Gujarat and Chennai studies were even representative of the total MDR-TB numbers. In fact, an unnamed microbiologist in these studies mentioned that the government doesn’t like to see high numbers in MDR-TB rates, and therefore the political pressure is on to keep the numbers low (whether it was actually achieved or not). Due to this, most critics are in favor of more rationality and quality of innovations to properly map MDR-TB and bring transparency with the public.

While some of this has already been mentioned in the sociocultural factors section of this paper, multiple drawbacks in the system lead to a lot of discrepancies in the health infrastructure of health facilities like hospitals and clinics. A lot of cases (according to the paper linked at the top of the section) occur due to mismanagement and poor treatment; many times, it ends up being in the hands of the patients, but also can stem from the health professionals in establishments. Central TB Division officers label MDR-TB as a problem created by external factors and the actors themselves (due to lack of regulation and mistreatment at the most direct level, not to mention nonadherent patients). However, critics argue that this is just a narrative pushed by the program to hide its own shortcomings. In reality, this ends up being a little bit of both; while drug pressure does exist with growing strength of TB with each infection and higher malnutrition of a country (making a better “playing ground”).

To add on, DOTS and other standard current TB treatments can also fail if improper direct supervision and little cooperation with the private sector occurs. The private sector, consisting of about 63 million microbusinesses (with over 10,000 of those microbusinesses as recognized health organizations), is probably the most large and far-reaching influential organizational entity in India, across both urban and rural areas (although they do tend to be way more concentrated in urban areas). One issue with the current health system is a noticeable lack of communication and coordination with the private sector, which can lead to many sometimes unscrupulous local healthcare workers deliver improper treatments and drugs to TB patients and may not report proper numbers, distorting the true validity of current data and the effectiveness of the program. If the private sector ends up being regulated by the Central TB Division, multiple local healers and ethnomedical professionals can be held accountable while also having their voices heard on possible holistic treatments, leading to breakthroughs in TB treatment and curbing the rise of resistance.

Conclusion, and Suggestions For the Way Forward

Addressing the growing MDR-TB crisis, in summary, will need a lot more avenues of research and problem-solving than the current steps and solutions being devised to merely keep it at bay. The high emphasis on the biomedical aspects of tuberculosis in India (in general) is unfortunately masking the equally important sociocultural aspects and phenomena that occur with Indian tuberculosis. Therefore, to address these aspects as well, an integrated medical approach is needed; the medical community should not only address the biomedical aspects of tuberculosis, but also take into account the sociocultural and economic aspects which are arguably equally important in vulnerable areas like India.

However, this is easier said than done when trying to scale the full scope of this ambition. However, apart from making necessary changes to the Indian public health system, a great starting point is to build cultural competency and sensitivity with Indian patients, no matter the health professionals ’ qualifications, degree, or amount of knowledge. Respecting the patients ’ perspectives, and smoothly guiding them in the right direction with their cultural beliefs about TB and the appropriate hybrid treatment plans that can combine Ayurvedic medicine and allopathic medicine with alleviations to social conditions, can ultimately result in a more culturally respectful environment in multiple rural and religiously devoted regions that can holistically address TB’ s rising antimicrobial resistance. It can also help break stereotypes commonly associated with the healthcare field, various types of health professionals and treatments, and personal psychological evaluations about one ’ s own health.

In a time when systemic and socioeconomic discrepancies have exacerbated the destructive nature of the recent COVID-19 pandemic in multiple countries, these disparities can serve as a learning moment for India and its Central TB Division to improve their main public health system, mode of testing, cost-effectiveness, reach, and sociocultural sensitivity. Tuberculosis is a curable disease, and yet it is still the most prevalent infectious disease in India to this day; hopefully that changes soon.

Bibliography

Aftab, A. (2024, June 27). Small business, big impact: Empowering women for Success. IFC. https://www.ifc.org/en/stories/2024/small-business-big-impact

Asian Pacific American Advisory Group. (2011). Health Care Providers ’ handbook on Hindu patients. AAHII Info. https://aahiinfo.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Healthcare-Handbook_Hindu.pdf Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). History of W orld TB Day.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/world-tb-day/history/?CDC_AAref_Val=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov %2Ftb%2Fworldtbday%2Fhistory.htm

Deshmukh, R. D., Dhande, D. J., Sachdeva, K. S., Sreenivas, A., Kumar, A. M. V., Satyanarayana, S., Parmar, M., Moonan, P. K., & Lo, T. Q. (2015, August 14). Patient and provider reported reasons for lost to follow up in MDRTB treatment: A qualitative study from a drug resistant TB Centre in India. PLOS ONE. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0135802

Government of India. (2025, September 26). About US – central tuberculosis division. Central Tuberculosis Division. https://tbcindia.mohfw.gov.in/about-us/

India, F. (2025, March 5). Poverty rate in India [2024]: Trend over the years and causes. Poverty rate in India: Trend over the years and causes. https://www.forbesindia.com/article/explainers/poverty-rate-in-india/90117/1

Lantz, P. M., Goldberg, D. S., & Gollust, S. E. (2023, April 25). The perils of medicalization for population health and health equity – lantz – 2023 – the Milbank Quarterly – Wiley Online Library. Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1468-0009.12619

Make In India. (2025). Sector highlights: Pharmaceuticals | Make in India. https://www.makeinindia.com/sector-highlights-pharmaceuticals

Mandal, S., Rao, R., & Joshi, R. (2023a, March 24). Estimating the burden of tuberculosis in India: A modelling study. Indian journal of community medicine : official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10353668/#:~:text=We%20estimated%20total%20 TB%20incidence,was%2023%20and%2027%20respectively

Mandal, S., Rao, R., & Joshi, R. (2023b, March 24). Estimating the burden of tuberculosis in India: A modelling study. Indian journal of community medicine : official publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10353668/#:~:text=We%20estimated%20total%20 TB%20incidence,was%2023%20and%2027%20respectively

Mandaviya, M. (2022, March 24). India TB Report 2022 – coming together to end TB … TBC India. https://tbcindia.mohfw.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/TBAnnaulReport2022.pdf

Watters, E. (2010, January 10). The Americanization of mental illness – The New York Times. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/10/magazine/10psyche-t.html

World Health Organization. (2024). Tuberculosis resurges as top infectious disease killer. https://www.who.int/news/item/29-10-2024-tuberculosis-resurges-as-top-infectious-disease-kill er

About the author

Akshar Belaguly

Akshar is currently a freshman at Brown University concentrating in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and wrote the paper while he was a senior at Gretchen Whitney High School in Cerritos, California. Some of his academic interests include biochemistry, genetics, and analytical chemistry, but he also has a deep fascination with medical anthropology that will hopefully give him holistic perspectives in his journey to medical school.

In addition, Akshar has also been part of his school’s Science Olympiad team, loves to watch and play cricket and basketball, and loves to spend time with his family in his free time.