Author: Madeline Farnsworth

Mentor: Nikolas R. Webster, Ph.D.

Palos Verdes High School

Abstract

Sports injuries are common across all levels of athletic participation, but anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears represent one of the most serious and career-altering conditions, particularly for female athletes in high-intensity sports like basketball. This paper examines the multifactorial causes, impacts, and prevention strategies of ACL injuries, with a specific emphasis on women’s basketball. Drawing from current literature, the study outlines sport-specific injury patterns, the anatomy and function of the ACL, and the factors of anatomical, hormonal, and neuromuscular risks that contribute to the elevated risk in female athletes. The discussion highlights both the physical and psychological consequences of ACL tears, including long rehabilitation periods, fear of re-injury, and decreased performance. Evidence-based prevention strategies, such as neuromuscular training, plyometrics, and biomechanical education, are reviewed, with emphasis on their demonstrated effectiveness in reducing non-contact ACL injuries in female basketball players. While research supports the value of these interventions, barriers to consistent implementation remain. The paper concludes that integrating targeted, sport-specific prevention programs into regular training is essential to reducing ACL injury incidence and preserving long-term athlete health and performance.

Introduction

Sport injuries are very common and can happen to anyone who exercises. According to the Cleveland Clinic (2024), a sport injury is a body injury while participating in any type of physical activity. Some of them happen suddenly, like when someone gets injured after falling, colliding with another player, or twisting a joint while in the midst of a game. Other injuries build up over a period of time, usually as a result of overuse. When the same motions are performed too frequently by a player, muscles and joints become inflamed and weakened and ultimately lead to injuries.

Sports injuries have many different causes. Injuries may be caused by an athlete’s improper form, failure to warm up, poor or imbalanced muscles, or overuse (Cleveland Clinic, 2024). The risk of getting hurt may also depend on the sport, the athlete’s gender and age. There are injuries that tend to happen more with younger athletes because they are growing, and other injuries tend to happen more with older athletes because their bodies are more utilized. Similarly, female athletes are more likely to get certain injuries than males, which shows that many factors come into play when it comes to sports injuries. The most common sports injuries overall are, sprains, strains, fractures, dislocations, tendonitis, and concussions (Cleveland Clinic, 2024). Which ones have a greater likelihood is based on the sports and the movements of the sport (Stephenson, 2021).

This paper examines the complex nature of ACL injuries across sports, with a focused lens on female athletes and the sport of basketball. Topics include the types of injuries common in different sports, the specific anatomy and function of the ACL, and why women are more prone to these injuries. It also explores the psychological toll of recovery, as well as the science-backed prevention strategies designed to reduce ACL risk, particularly those that have shown success in women’s basketball. Understanding the multifaceted causes and solutions to ACL injuries is critical for protecting athletes and extending their careers.

Injuries Within Specific Sports

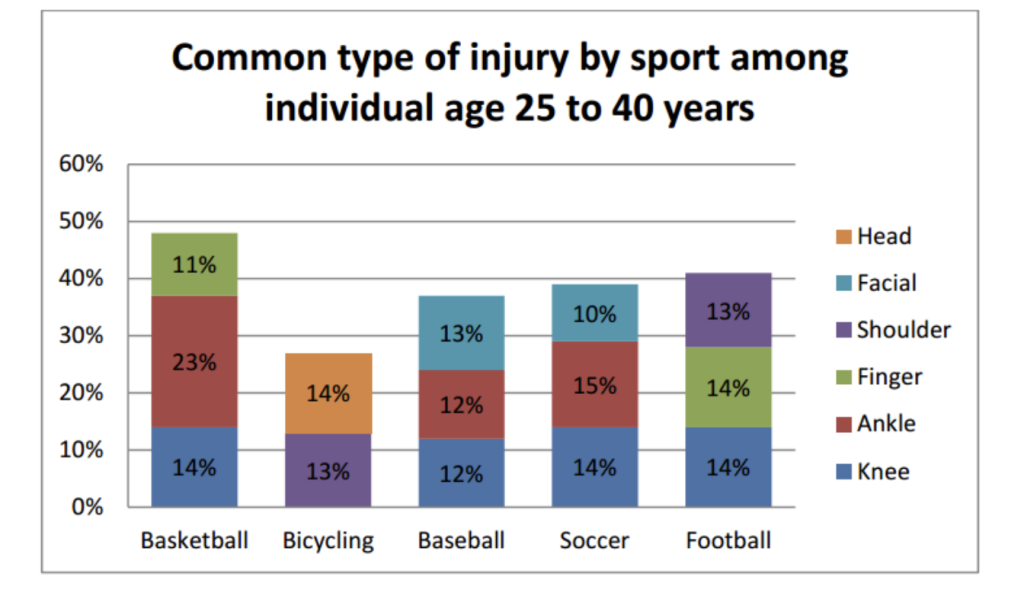

While all athletes are prone to injury while participating in sports, there are more dangerous sports than others (Stephenson, 2021). Contact sports like football and hockey generate more traumatic injuries, including concussions, fractures, and dislocations, because athletes collide into each other and take hard falls. In football, concussions and knee ligament tears are the most common and serious (Gessel, 2007).

Non-contact sports like swimming and running are generally safe in terms of sudden trauma, but they can experience overuse injuries, like tendonitis or stress fractures, from repeatedly doing the same motion (Cleveland Clinic, 2024). In long-distance runners, stress fractures in the tibia and metatarsals are especially prevalent due to the repetitive impact on hard surfaces (Warden, 2014). Swimmers commonly suffer from shoulder impingement and rotator cuff issues due to high volume of overhead motion (Bak, 2010).

Some sports carry both risks. Taylor (2015) highlighted that basketball and soccer are sports of high velocity, in which sprinting, jumping, quick changes of direction, and even collisions at times are involved. All these activities cause maximum stress on the lower extremities. Basketball has one of the highest injury rates of any team sport, with the majority of injuries happening in the lower body (Taylor, 2015). Different sports stress different parts of the body, and understanding these patterns can help athletes, coaches, and trainers get their prevention strategies.

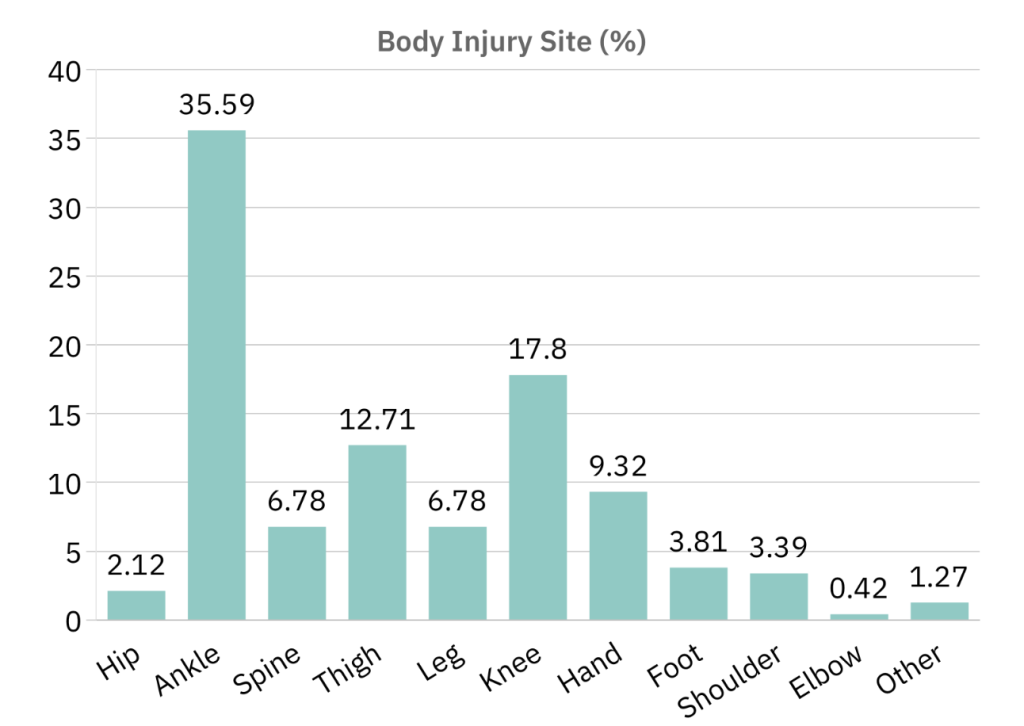

Injuries can affect many parts of the body and often cause pain and difficulty with movement (Griffin, 2006). Among these, injuries to the lower limbs are especially common and can significantly impact a person;s ability to perform everyday activities.The knee joint allows movements like walking, running, and jumping. One of the most frequent knee injuries involves the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), which is crucial for stabilizing the knee during any physical activity. ACL injuries are especially common in athletes and can lead to long-term problems such as joint instability and even early arthritis if not properly treated (Lohmander, 2007).

While different sports tend to produce distinct types of injuries based on their unique demands and risks, one injury stands out across many athletic activities. The ACL ligament tear is very common whether in high-contact sports or in fast-paced sports that require sudden changes in direction, ACL injuries are a common and serious problem. This ligament plays a key role in stabilizing the knee during movement, making it vulnerable during sports that involve high-impact motions. Due to its importance and frequency, ACL injuries have become a major focus in sports medicine.

ACL Injuries in Sport

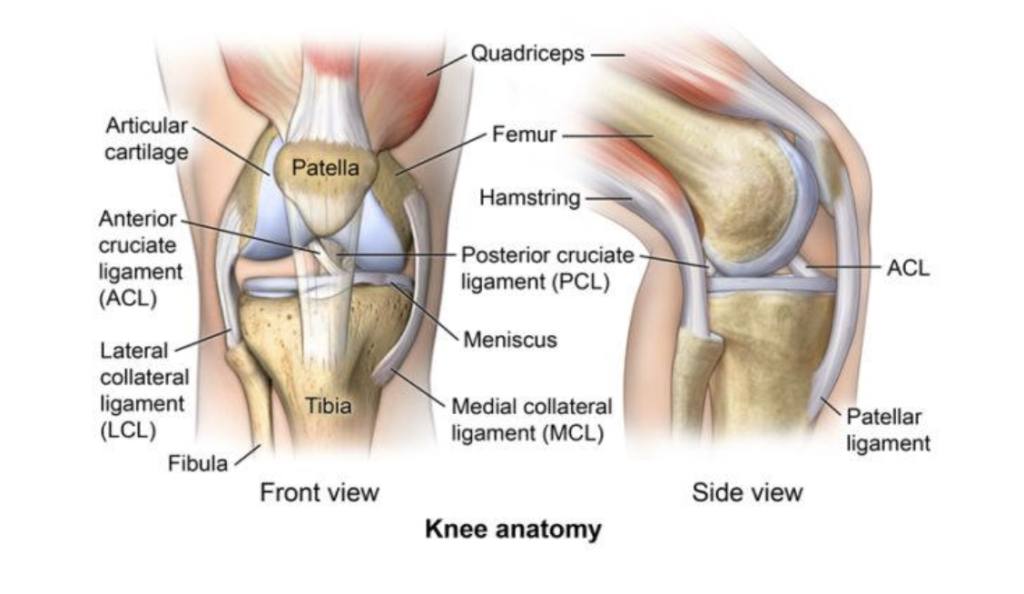

One of the most serious and well-known sports injuries is an ACL injury. The knee joint is made up of several main ligaments, including the medial collateral ligament (MCL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), and the anterolateral ligament (ALL), all of which work together to provide stability and control movement. The ACL is one of the major four knee ligaments. Park (2022) explained that it functions to stop the tibia from moving too far forward in relation to the femur and also helps control rotational knee movement. The knee is one of the largest and most complex joints in the body, made up of bones, ligaments, tendons, and muscles that all work together to allow movements like running, walking, and jumping. Once the ACL is ruptured, the knee becomes unstable and it may be very hard to keep playing sports without surgery and a long recovery. ACL injuries are extremely common in sports that have a lot of sudden stopping, sudden changes of direction, and jumping and landing. Since the movement is such a major part of so many sports, ACL injuries are a big problem for many athletes.

In addition to the ACL, the knee relies on other key anatomical structures to maintain its function and stability. The anterolateral ligament (ALL), located on the outer front portion of the knee, originates near the lateral femoral epicondyle and inserts onto the anterolateral tibia (Park, 2022). It plays a key role in controlling internal tibia rotation and works in coordination with the ACL, especially when the knee is flexed. The iliotibial band (ITB) and the deep capsulo-osseous layer are also important components of the anterolateral complex, contributing to resistance against rotational forces (Park, 2022). Together, these elements form a system that helps stabilize the knee during cutting, pivoting, and landing motions common in many sports.

While ACL injuries are a serious concern for all athletes due to the knee’s complex structure and the ligament’s key role in stability and movement, research shows that women are at a significantly higher risk for these injuries compared to men (Park, 2022). Factors such as anatomical differences, hormonal influences, and neuromuscular control variations contribute to this increased vulnerability among female athletes. Sports that involve sudden stops, cutting, and jumping put female athletes at particular risk for ACL tears, making it important to understand how these injuries affect women differently and to develop prevention strategies tailored to their needs.

ACL Injuries for Women in Sports

Female athletes are more likely to have an ACL injury than male athletes who play the same sports (Ireland, 1999). Huston’s (2000) research has determined that women are about 2 to 8 times more likely to sustain an ACL tear than men. This is especially true for sports like soccer and basketball, which require quick movements and jumping are required but not necessarily colliding with another player. There are numerous reasons women are more prone to ACL tears. They also carry a greater risk from anatomical, hormonal, and neuromuscular risks. Females generally have wider hips, and their knees will tend to angle inward more, placing more stress on the joint. They also tend to use their quadriceps more and their hamstrings less when stabilizing the knee, increasing more stress on the ACL (Huston, 2000).

Huston (2000) also explained that males engage their hamstrings, this provides tibial protection and shifts the stress away from the ACL. Hormonally, there are two hormones, estrogen and relaxin, which are modified throughout the menstrual cycle and may make ligaments more flexible and weaker at certain times, increasing injury risk (Huston, 2000).

Athletes at the highest level have experienced ACL injuries, highlighting the prevalence of this injury in women’s sports. For instance, soccer star Alex Morgan, a key player for the U.S. Women’s National Team and Olympic gold medalist, tore her ACL during her high school career in 2007, which required surgery and rehabilitation before she returned to top-level play (Sterett, 2025). Similarly, tennis player Venus Williams suffered a knee injury related to ligament damage in 2023, which affected her performance and led to a period of recovery (Ramchandani, 2023). These examples emphasize the physical challenges female athletes face and highlight the importance of targeted prevention and recovery strategies for ACL injuries.

Among the various sports where female athletes face a high risk of ACL injury, basketball stands out as one of the most affected. The combination of rapid direction changes, frequent jumping, and quick stops makes the sport demanding on the knee joint. As discussed earlier, female athletes already face such elevated risks due to a variety of factors. In basketball, these risks are heightened by the fast pace and physical demands of the game, placing constant stress on the lower extremities. As a result, ACL injuries have become not only common but also career-altering for many women basketball players, making it critical to explore the unique challenges they face within the sport.

ACL Injuries in Women’s Basketball

ACL injuries are a major issue in women’s basketball, representing one of the most frequent and severe lower-extremity injuries sustained in the sport (Stojanović, 2023). Female basketball players are at an even greater risk for ACL injuries than male players. Up to 16% of female basketball players will tear their ACL at some point in their career, which is about two to four times higher than the risk for males (Taylor, 2015). These injuries typically occur during high-intensity movements such as landing from a jump, abrupt deceleration, or cutting laterally. These are all actions that are integral to basketball (Huston, 2000). According to systematic data, ACL injuries account for a significant portion of time-loss injuries and often require surgical reconstruction and extensive rehabilitation. These injuries frequently occur during solo movements like jump landings, particularly when athletes land on a single leg or in an unbalanced position (Huston, 2000).

Unlike many contact-related injuries, most ACL tears in basketball are non-contact related. These injuries frequently occur during solo movements like jump landings, particularly when athletes land on a single leg or in an unbalanced position (Huston, 2000). The repetition of these high-risk movements across practices and games places female basketball players at constant risk for ACL damage (Stojanović, 2023). For example, WNBA player Cameron Brink suffered a season-ending ACL injury as a rookie following an awkward landing during a game, illustrating how common such injuries are at elite levels (Ramkumar, 2025). Similarly, collegiate standout Paige Bueckers experienced an ACL tear early in her career that required surgery and extensive rehabilitation, highlighting the long recovery period and challenges of returning during peak performance (Philippou, 2023).

Huston (2000) claimed that ACL tears are not only season-ending injuries but often career-altering. Rehabilitation can last six months to over a year, depending on surgical outcomes and adherence to physical therapy protocols. Even with optimal recovery, many athletes do not return to their pre-injury performance levels. Studies have also shown a high rate of second ACL injuries, either to the reconstructed knee or the opposite one, within two years of return to sport. These recurring injuries can lead to chronic instability (Huston, 2000).

While the physical impact of ACL injuries on female basketball players is profound, the psychological effects are equally and often overlooked. The long recovery process, uncertainty about returning to their pre-injury performance level, and fear of re-injury can significantly affect an athlete’s mental health and motivation during rehabilitation. Understanding these psychological challenges is crucial for supporting athletes through recovery and improving overall outcomes.

Psychological Considerations of ACL Injuries

Huston (2000) also explained the psychological effects often accompany the physical consequences of ACL injury. Fear of reinjury, lack of confidence, and hesitation during gameplay are commonly reported in female basketball players post-ACL reconstruction.. Athletes frequently modify their playing style after returning, which may further compromise performance or lead to compensatory injuries (Huston, 2000). Hart’s (2020) recent research underscores the fear of reinjury, often referred to as “kinesiophobia,” is a major psychological barrier to returning to sport and is strongly associated with poorer functional outcomes, reduced knee confidence, and reduced readiness to return to pivoting sports one year post surgery.

Russell’s (2024) further studies reveal that athletes who experience persistent reinjury anxiety or perceived limitations after surgery may delay or fail to return to their respective sport altogether, and those with higher fear are more likely to suffer a second ACL injury. Moreover, Christino (2015) found that rehabilitation following ACL reconstruction is often accompanied by significant mood disturbances, including anxiety, depression, lowered self-esteem, and emotional distress, which can negatively affect compliance, physical recovery, and overall outcomes. The high rate of ACL injuries in women’s basketball highlights an urgent need for sport specific injury management strategies.

These psychological challenges emphasize that ACL injuries are not only physically debilitating but also mentally and emotionally taxing, often hindering a full return to sport. Given the significant short- and long-term impacts on both performance and well-being, especially in female basketball players, it becomes clear that prevention is essential. By implementing targeted, sport-specific strategies aimed at reducing injury risk, athletes, coaches, and healthcare professionals can work proactively to mitigate both the physical and psychological toll of ACL injuries.

Prevention of ACL Injuries

Taylor (2015) had suggested that targeted injury prevention programs had shown a significant reduction in anterior cruciate ligament injury rates across sports. These programs are most effective when they incorporate a combination of plyometric drills, balance training, strength exercises, and exercises that reinforce proper landing and cutting techniques. Movements that focus on knee alignment and body control during single-leg landings and lateral changes in direction are particularly useful in reducing ACL strain (Taylor, 2015).

According to Stephenson, the consistent use of these interventions throughout a training cycle, particularly during the preseasons, has been linked to greater injury reductions. Many of these programs can be built into warm-ups and regular team practices, making them accessible even in resource-limited settings. However, their success depends on athletes receiving proper instruction and coaches ensuring that exercises are performed with correct form (Stephenson, 2021).

Yung (2021) emphasizes that injury prevention should also be viewed as part of a bigger picture, where injury risk is influenced by multiple interacting variables like training load, fatigue, emotional stress, and environmental factors. Effective strategies should not only train specific movement skills but also adapt to the context of the athlete’s current condition and recent workload. Adjustments to training intensity during periods of fatigue or mental burnout can reduce the likelihood of movement errors that may lead to ACL injury (Yung, 2021).

Preventative efforts are most effective when customized to the individual. Differences in age, sex, injury history, and performance level all affect how an athlete responds to a given intervention (Yung, 2021). Flexible and responsive programming, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, supports both injury reduction and long-term performance sustainability (Yung, 2021).

Despite strong evidence, many teams still fail to consistently use proven prevention strategies due to barriers such as time constraints, lack of coach education, and limited access to medical professionals (Stephenson, 2021). Integrating these practices into the daily structure of team training, especially during high-risk phases of the season, can help overcome these challenges and improve athlete safety (Taylor, 2015).

A well-designed, regularly executed prevention program, one that combines biomechanical training with adaptable load management, offers one of the most effective ways to protect athletes from ACL injuries while promoting safer performance overall. Prevention of ACL Injuries in Women’ s Basketball

In women’s basketball, the implementation of targeted ACL injury prevention strategies is essential. With a high rate of non-contact ACL injuries occurring during landing, cutting, or decelerating, programs that focus on neuromuscular control, strength development, and proper technique have been shown to significantly reduce injury risk (Taylor, 2015). Rigorous, evidence-based prevention programs that integrate neuromuscular training, plyometrics, strength conditioning, and feedback on landing mechanics have demonstrated substantial reductions in ACL injury risk. Research shows that neuromuscular training (NMT) can reduce non-contact ACL injury risk by approximately 73% and overall ACL injuries by roughly 44% in female athletes (Sugimoto, 2012). Additionally, programs including plyometric exercises have been associated with up to a 60% reduction in ACL injury risk (Al Attar, 2022).

Such training improves crucial biomechanical markers like increased knee flexion and decreased knee valgus during landing, which are all movement characteristics associated with lower ACL strain (Ramachandran, 2025). Targeted NMT can also specifically reduce high-risk knee abduction moments in female athletes, enhancing safety during dynamic sports actions (Myer, 2007).

Additionally, a 6-week plyometric jump-training regimen for female collegiate basketball players revealed significant gains in hamstring strength and hamstrings-to-quadriceps ratio, parameters essential for dynamic knee stability and an important protective factor against ACL injury (Wilkerson, 2004). Moreover, multimodal prevention programs combining plyometrics, strength training, flexibility, and education about landing mechanics effectively decreased overall knee injury rates in female basketball players, and were even more effective when implemented prior to the sports season (V oskanian, 2013).

In high-profile cases like Paige Bueckers, her post-injury comeback has been supported by a dedicated rehabilitation schedule incorporating biomechanics analysis, pilates, strength work, and neuromuscular feedback, highlighting how personalized, science-driven practices support both injury prevention and performance maintenance (Philippou, 2023). Cameron Brink, who suffered an ACL tear early in her professional career, emphasized in interviews how relearning neuromuscular control for movements like cutting and jumping was vital during her rehabilitation, a reminder that prevention should extend into post-injury retraining (Dalzell, 2024).

Despite strong evidence supporting these protocols, many women’s basketball programs still fall short in implementation due to constraints like limited training time, insufficient coach education, and lack of access to sports medicine resources. Embedding these prevention strategies as consistent, sport-specific warm-ups, particularly during preseason and maintained in-season, offers a path forward to protect athletes’ health and extend their competitive longevity.

Conclusion

Sports injuries are an inevitable part of athletics, affecting athletes across all types of sports, levels, and ages. While some injuries happen from sudden trauma, others result from overuse and poor mechanics, highlighting the complex and many factors of injury risk. Among the types of injuries, ACL tears stand out as one of the most severe and prevalent, particularly in sports that involve intense movements like jumping, pivoting, and rapid changes in direction. Female athletes, especially in high-intensity sports like basketball and soccer, are at significantly greater risk of ACL injuries due to a combination of anatomical, hormonal, and neuromuscular factors. These injuries not only impact performance and require rehabilitation but they also carry a high risk of re-injury and long-term psychological and physical consequences.

The high incidence of ACL injuries, particularly in female athletes, underscores the importance of targeted prevention strategies. Research shows that injury prevention programs that incorporate strength training, neuromuscular education, proper landing techniques, and individualized load management can significantly reduce the occurrence of ACL injuries. However, consistent implementation remains a challenge due to time constraints, lack of awareness, and resource limitations.

To effectively address ACL injuries in sports, particularly among female athletes, there must be a shift in how prevention is prioritized. Coaches, trainers, and athletes need to be educated on the value of these programs, and teams must make them a consistent part of their training routines. Ultimately, injury prevention is not just about avoiding setbacks, it is about preserving the long-term health, performance, and careers of athletes. With the right strategies in place, many of these injuries are preventable, and the athletic experience can be made safer and more sustainable for all participants.

Limitations

While this paper provides a comprehensive overview of ACL injuries in female athletes, particularly within basketball, there are several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, this study did not include primary qualitative data from athletes who have experienced ACL injuries, such as interviews or surveys of female basketball players recovering from or living with ACL tears. Incorporating these firsthand accounts would add depth to the understanding of the psychological and physical challenges faced during rehabilitation, offering more personalized insights beyond the existing literature. Additionally, quantitative data specific to injury rates and prevention program effectiveness within different levels of competition (high school vs. collegiate vs. professional) were not extensively analyzed. Including such data would help clarify how risk factors and prevention strategies may vary across different athlete populations.

Future Research

Future research should explore the influence of playing surfaces on the risk of ACL and other knee injuries in female basketball players. Different court materials, such as hardwood, synthetic floors, concrete, and asphalt may affect traction and joint stress, potentially altering injury rates and severity. Investigating how these surfaces contribute to ACL injuries or combinations of knee injuries could guide safer playing environments and inform sport facility design.

Another important area for further study is the occurrence and impact of multiple concurrent knee injuries, such as ACL tears combined with lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injuries or patellar tendon tears. These complex injury patterns may result in more severe instability, longer recovery times, and unique rehabilitation challenges. Understanding the biomechanical and physiological factors that contribute to multi-ligament knee injuries would improve treatment protocols and prevention strategies tailored to these more complicated cases.

References

Al Attar, W.S.A., Bakhsh, J.M., Khaledi, E.H., Ghulam, H., & Sanders, R.H. (2022). “Injury prevention programs that include plyometric exercises reduce the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury: A systematic review of cluster randomised trials.” Journal of Physiotherapy, 68(4), 255–261.

Bak, K. (2010). “The practical management of swimmer’s painful shoulder: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment.” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 20(5), 386-390.

Christino, M. A., Fantry, A. J., & V opat, B. G. (2015). “Psychological aspects of recovery following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.” Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 23(8), 501–509.

Cleveland Clinic. (2022). “Sports injuries: Types, symptoms, causes & treatment.” Comprehensive Orthopedics, S.C. (n.d.). “Anatomy of the Knee. Comprehensive Orthopedics. Dalzel, N. (2024). 1-on-1 with Cameron Brink: on her rookie season, outstanding defense, and the growth of women’s basketball.” SB Nation.

Gessel, L. M., Fields, S. K., Collins, C. L., Dick, R. W., & Comstock, R. D. (2007). “Concussions among United States high school and collegiate athletes.” Journal of Athletic Training, 42(4), 495-503.

Hart, H. F., Culvenor, A. G., Guermazi, A., & Crossley, K. M. (2020). “Worse knee confidence, fear of movement, psychological readiness to return‑to‑sport and pain are associated with worse function after ACL reconstruction.” Physical Therapy in Sport, 41, 1–8.

Huston, L. J., Greenfield, M. L., & Wojtys, E. M. (2000). “Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the female athlete: potential risk factors.” Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research, 372, 50-63.

Ireland, M. L. (1999). “Anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: Epidemiology.” Journal of Athletic Training, 34(2), 150-154.

Lohmander, L.S., Englund, P.M., Dahl, L.L., & Roos, E.M. (2007). “The Long‑term Consequence of Anterior Cruciate Ligament and Meniscus Injuries: Osteoarthritis.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 35(10), 1756–1769.

Misra, A. (2014). “Common sports injuries: Incidence and average charges.” U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

Musculoskeletal Key. (2016). “Basketball: Epidemiology and injury mechanism.”

Myer, G.D., Ford, K.R., Brent, J.L., & Hewett, T.E. (2007). “Differential neuromuscular training effects on ACL injury risk factors in “high-risk” versus “low-risk” athletes.” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 8, 39.

Park, J. -G., Han, S. -B., Lee, C. -S., Jeon, O. H., & Jang, K. -M. (2022). “Anatomy, biomechanics, and reconstruction of the anterolateral ligament of the knee joint.” Medicina, 58.6.

Philippou, A. (2023). “Faith, science and Pilates fuel Paige Bueckers’ UConn return.” ESPN.

Philippou, A. (2023). “UConn’s Paige Bueckers ‘very close’ in recovery from ACL tear.” ESPN.

Ramachandran, A.K., Pedley, J.S., Moeskops, S., Oliver, J.L., Myer, G.D., Hsiao, H.-I., & Lloyd, R.S. (2025). “Influence of neuromuscular training interventions on jump-landing biomechanics and implications for ACL injuries in youth females: A systematic review and meta-analysis.” Sports Medicine, 55(5), 1265–1292.

Ramchandani, H. (2023). “I spent the whole summer pretty injured with my knee, like really struggling with it” – Venus Williams. Sports Illustrated.

Ramkumar, P. N. (2025). “Cameron Brink ACL injury, WNBA.” WNBA News.

Russell, H. C., Arendt, E. A., & Wiese‑Bjornstal, D. M. (2024). “Psychological responses during latter rehabilitation and return to sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery.” Journal of Athletic Training, 59(6), 627–632.

Stephenson, S. D., Kocan, J. W., Vinod, A. V ., Kluczynski, M. A., & Bisson, L. J. (2021). “A comprehensive summary of systematic review on sports injury prevention strategies.” Sports Medicine, 51(3), 487-504.

Sterett, B. (2024). “High-Level ACL Repair.”

Stojanović, E., Faude, O., Nikić, M., Scanlan, A. T., Radovanović, D., & Jakovljević, V . (2023). “The incidence rate of ACL injuries and ankle sprains in basketball players: A systematic review and meta-analysis”. Sports Medicine, 9(1), 20.

Sugimoto, D., Myer, G.D., Mckeon, J.M., Hewett, T.E. “Evaluation of the effectiveness of neuromuscular training to reduce anterior cruciate ligament injury in female athletes: a critical review of relative risk reduction and numbers-needed-to-treat analyses.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(14), 979–988

Taylor, J. B., Ford, K. R., Nguyen, A. D., Terry, L. N., & Hegedus, E. J. (2015). “Prevention of lower extremity injuries in basketball: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Sports Health, 7(3), 265-273.

Voskanian, N. (2013). “ACL injury prevention in female athletes: Review of the literature and practical considerations in implementing an ACL prevention program.” Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 6(2), 158–163.

Warden, S. J., Davis, I. S., & Fredericson, M. (2014). “Management and prevention of bone stress injuries in long-distance runners.” Journal of Orthopedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 44(10), 749-765.

Wilkerson, G. B., Colston, M. A., Short, N. I., Neal, K. L., Hoewischer, P. E., & Pixley, J. J. (2004). “Neuromuscular changes in female collegiate athletes resulting from a plyometric jump-training program.” Journal of Athletic Training, 39(1), 17–23.

Yung, K. K., Arden, C. L., Serpiello, F. R., & Robertson, S. (2022). “Characteristics of complex systems in sports injury rehabilitation: examples and implications for practice.” Physical Therapy in Sport, 53, 154-163.

About the author

Madeline Farnsworth

Maddie is a senior at Palos Verdes High School in Southern California, where she excels as a three-sport athlete, competing in basketball, cross country, and track. Her passion for athletics extends beyond competition as she is deeply interested in how sports impact the body and mind, and she plans to pursue this field in the future. Whether on the court or in the classroom, she is dedicated, driven, and committed to understanding the science behind peak performance and overall well-being.