Author: Bill Wu

Mentor: Dr. Eric Golson

Western Reserve Academy

The Taiwan Strait is considered to be one of the most tense areas in the world, but despite this, the area has not been the scene of a major armed conflict since the Second World War. Even though the situation is perceived to be tense, both China and Taiwan have been able to manage their differences reasonably well. Over the period 1996-2022, the situation in the Taiwan Strait was seen as controllable. After the 1996 Taiwan Strait crisis, the overall military tension between the two sides was in a stable state. Encounters were generally dealt with diplomatically. This trend was irrevocably reversed when Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan in 2022. China has normalized its military deterrence against Taiwan and has expressed peaceful reunification less and less in public. The United States’ more aggressive calls against unilateral changes to the status quo in the Taiwan Strait rhetorically confirm the 2022 change.

Despite the existence of different opinions, historians and sociologists still generally agree that Mainland China and Taiwan belong to the same core range of the Greater China Cultural Circle, speak Chinese, share similar cultural practices, and are genetically similar. And unlike the multi-ethnic countries in Southeast Asia where some Chinese are part of the population, both Mainland China and Taiwan are countries where Han-ethnicity is the majority.

The issue of the Taiwan Strait is legally an extension of the civil war between the Communist Party of China (CPC) and Kuomintang (KMT). Which means that the Mainland China and Taiwan are still in a nominal state of war, and the two sides have not signed an armistice agreement of any kind. Therefore, legally speaking, the Taiwan authorities represent the Government of the Republic of China (ROC), while mainland China represents the Government of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

I. History and Analysis of Mainland China’s Policy toward Taiwan

1. Mao Zedong’s China–Postscript to the Revolution

In 1949, the Communist Party of China (CPC) recovered most of the China’s land, and the strategic decision made by Chiang Kai-shek under the leadership of the Kuomintang (KMT) was to withdraw to Taiwan. There is an old Chinese saying “when there are green hills, there will be wood to burn”, which means that as long as the Kuomintang (KMT) regime, army and financial resources are still there, there will be a chance to regain the whole of China, and it would be better to retreat to Taiwan rather than fighting the Communist Party of China (CPC) on the ultra-long front in Mainland China. In hindsight, Chiang Kai-shek made the right defensive decision. The Communist Party of China (CPC) lacked sufficient amphibious and sea-crossing capabilities at the time. Additionally, they were able to rely on the U.S. containment strategy against communism, with the Americans regularly sending the Seventh Fleet to patrol the Taiwan Strait.

In addition to the military reasons, China’s domestic economy was poor and not improving: people’s lives were in ruins because of the years of war. The Communist Party of China (CPC) long relied on popularity and the masses to gain an advantage in the civil war; but then failed to deliver economic growth. It was well known that if the Communist Party of China (CPC) fails to gain the confidence of the people in the short term, it may trigger a new round of civil war. Therefore, the Communist Party of China (CPC) needed to divert a lot of energy from domestic reconstruction. At the same time, with the outbreak of the Korean War, the Communist Party of China (CPC) needed to devote a large amount of military resources to the Korean battlefield. At the end of the Korean War, Mainland China’s military strength was greatly depleted, and the Kuomintang (KMT) had already carried out five years of social and military construction in Taiwan. It can be said at time neither the Kuomintang (KMT) nor the Communist Party of China (CPC) had the ability to launch a large-scale offensive against the other side.

Unable to do much else given their weak positions, both Communist Party of China (CPC) and the Kuomintang (KMT) resorted to low-cost ideological war on the other side’s territory. The Kuomintang (KMT) carried out destructive operations by planting spies and agents in Mainland China. The Communist Party of China (CPC) supported the communist movement in Taiwan. So although CPC continued to claim that Taiwan was the territory of the People’s Republic of China, it used the communist movement to try to dismantle the Kuomintang (KMT)’s dictatorship in Taiwan.

There are even claims from Taiwan side that in the 1960s, with the Cultural Revolution taking place and the gap between Mainland China’s overall power and Taiwan’s widening, Mao Zedong had wanted Taiwan to become independent. Doing so would have allowed the international community to fully recognize the Communist Party of China (CPC) as the sole government representing Mainland China and resolving the long-standing problems of international recognition.

However, the CPC need for Taiwanese independence changed with a series of political events such as the People’s Republic of China gaining a seat in the United Nations, Nixon’s visit to China, and the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the United States. In 1972 with Nixon’s visit to China, the Shanghai Communiqué was issued, recognizing there was only one China, but not stating the Government of the People’s Republic of China was the sole legitimate government representing China. In the same year, the U.S. and China signed the August 17 Communiqué, which reaffirmed the “one China” policy, while the U.S. side promised to gradually reduce arms sales to Taiwan and ultimately reach a solution to the issue.

Of course, this position was ultimately a realist move to end the war in Vietnam and was pragmatically self-serving for Nixon; it did not necessarily mean the United States exclusively supports the one-China policy. With the 1972 election approaching, Nixon was trying to end the Vietnam War. He had already committed to end the Vietnam War during his successful 1968 campaign, but the United States was still stuck in Vietnam when he was being re-elected. With China as the main supporter of North Vietnam, the U.S. provided China with some benefits, including a declaration about one China policy; it was convinced North Vietnam not to attack South Vietnam and the U.S troops when the U.S. withdrew from Vietnam, and provided Nixon with political capital during the U.S. campaign season in which he could brag that the U.S. had won a victory in Vietnam.

Overall, during the Maoist era, the Mainland China’s policy toward Taiwan shifted to a forced expression of peaceful intentions based on limited strength. However, building a dominating force remained a priority consideration, and the Communist Party of China (CPC) conducted a number of military deterrence operations against Taiwan in the 1950s and 1960s. Mao died in 1976, and the Cultural Revolution ended after a series of intra-party battles within the Communist Party of China (CPC).

2. Deng Xiaoping’s China–One Country, Two Systems

Mao’s health was not what it used to be in the 1970s, and he did not see the day when China and the United States fully establish diplomatic relations. After Mao’s death, the Communist Party of China (CPC) went through a series of internal fights. The first was the purge of the Gang of Four, also known as the Huairentang Incident, which established the end of the Cultural Revolution. Mao’s immediate successor was not Deng Xiaoping, but Hua Guofeng, who was considered the representative of the conservative faction of the Communist Party of China (CPC), and continued to support Mao’s line, putting forward the famous “Two Whatever” ideology, which stated: We (CPC) will resolutely uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made. We (CPC) will unswervingly follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave.” This ideology was later used by Deng Xiaoping to weaken Hua Guofeng’s power and make him the leader of the Communist Party of China (CPC), as he gradually gained power and put forward the idea of “economic construction as the center” at the Third Plenary Session of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and further established the Communist Party of China (CPC)’s “Seek Truth from Facts” style of work, which made him the defacto leader of the Communist Party of China (CPC). This dramatic policy shift also pushed forward the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the United States.

On December 16, 1978, on the eve of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the U.S., both sides issued the Communique on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between China and the U.S. In the communiqué, the U.S. formally recognized the government of the People’s Republic of China as the sole legal government of China, acknowledged that Taiwan was a part of China, and severed diplomatic relations with Taiwan, terminating the Mutual Defense Treaty. At the same time, the United States emphasized the establishment of diplomatic relations with the Mainland China does not mean that it agrees with the Mainland China to resolve the Taiwan issue by force. In the same year, Deng Xiaoping visited the U.S., and the Chinese leader, who liked to smoke and was not very tall, made a deep impression on politicians and people in the United States.

The establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the United States and Deng’s visit to the U.S. marked the breaking of the ice in Sino-U.S. relations and an ideological alignment in the Cold War. Li Shenzhi, Vice President of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and Director of the Institute of American Studies, who accompanied Deng on his visit to the U.S., asked Deng on the plane, “Why do we attach so much importance to our relationship with the U.S.?” Deng replied, “The countries that followed the United States have become rich, while the countries that followed the Soviet Union are still poor.” He also suggested that “socialism is not characterized by poverty, but by wealth.” As the United States was mired in the Vietnam War, China wanted to open and develop; meanwhile border disputes with the Soviet Union further pushed China toward the United States. In the 1970s and 1980s, the world landscape was effectively one capitalist and one socialist country, China and the United States, united against the Soviet Union.

After the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and the U.S., the relationship between Mainland China and Taiwan has become more of a sub-topic of Sino-Western relations and Sino-U.S. relations. Under Deng Xiaoping, with the reform and opening up, any other issues were given way to the economy and the development of people’s livelihoods. Deng Xiaoping proposed the development strategy of “hide the strength, bide the time”, which was gradually abandoned until the Xi Jinping era. So at that time, political, diplomatic, and military goals would take precedence over economic ones.

During Deng Xiaoping’s leadership, Mainland China’s policy toward Taiwan can essentially be considered conciliation. In 1978, Deng Xiaoping visited Singapore, a country that was considered to be one of the dominant ethnic groups of the Chinese who practiced a good balance of democracy and order. Deng made a promise to Lee Kuan Yew that he would not export the revolution to Taiwan. The same was true in the case of Taiwan, where there was no concession in principle and the principle of one China (People’s Republic of China) was not changed. This ultimately promoted cross-strait exchanges.

At the same time, Deng put forward the policy of “peaceful reunification, one country, two systems”, and the one country, two systems formula currently in use in Hong Kong and Macao. This was first designed for the peaceful reunification of Taiwan. The core of this policy was to allow Taiwan to maintain its current social system and a high degree of autonomy while adhering to the “one China” principle, i.e., Taiwan could continue to maintain its capitalist system and enjoy a high degree of autonomy, while Mainland China continued to adhere to the socialist system. Deng Xiaoping made it clear Taiwan could retain its own military forces and that China would not send troops or administrators to Taiwan. Despite this, and in keeping with the longstanding and even current Communist Party of China (CPC) foreign policy, Deng also stated he would not rule out the use of force, even if his overall preference was strongly for peaceful reunification.

During this period, although there were various domestic political events within China, the overall trend of opening up to the outside world remained unchanged. The overall shift in the Communist Party of China (CPC)’s political stance from the extreme left to the left of center or even to the center helped significantly to improve the People’s Republic of China (PRC)’s political status globally, and secured the recognition of more countries and the severance of diplomatic relations with the Republic of China (ROC) Taiwan.

3. Jiangzemin’s China–From Conciliation to Deterrence

Jiang Zemin is considered to have been the most Western-like style leader in the history of the Communist Party. He speaks English and Russian fluently. Every leader in China seems to have unique political wisdom from a historical perspective, and Jiang Zemin is no exception. His eloquence in dealing with journalists demonstrates his wisdom. On the Taiwan issue, as more complex domestic reforms were carried out and the international situation shifted, Jiang became more flexible in his practical maneuvering on the Taiwan issue, but overall experienced a shift from conciliation to deterrence.

Although Jiang’s early period and Deng’s late period were themselves overlapping, during Jiang Zemin’s early years, Mainland China’s policy toward Taiwan was still a continuation of Deng Xiaoping’s late conciliation policy. The 1992 Consensus was signed in Hong Kong by Mainland China’s Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS) and Taiwan’s Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF). The 1992 Consensus recognized both sides of the Taiwan Strait were part of one China under a vague statement of principle. This is a legacy of Mainland China’s policy of conciliation with Taiwan, whereby the concept of “China” is strategically blurred to further expand exchanges with the Taiwanese side, to put the relationship between Mainland China and Taiwan on the track of benign and peaceful communication, and to curb the tendency towards independence.

China’s conciliation did not last long, on January 30, 1995, Jiang Zemin made his famous speech on Taiwan policy, in which he put forward “Jiang’s Eight Points” or “Eight Propositions”, which are regarded as the core elements of Jiang’s policy towards Taiwan. In general, the policy statement falls somewhere between Conciliation and Deterrence, but in view of the growing popularity of the island’s independence forces, the timing of Deterrence is preferred to prevent Taiwan from declaring independence. Later that year, Taiwan’s President Lee Teng-hui’s visit to the U.S. was seen as undermining the tacit diplomatic understanding of one China between China, the U.S., and Taiwan. The Mainland China viewed Lee’s visit as an attempt to promote “progressive Taiwan independence” and to enhance Taiwan’s diplomatic status by increasing its international influence as a subject to challenge the “one-China” policy.

During two important events, Lee Teng-hui’s visit to the United States and Taiwan’s first direct presidential election, Mainland China conducted two deterrent military exercises against Taiwan, involving missile launches and artillery shelling. As the exposure of the spying incident showed that at that time the Mainland China was prepared for direct forceful reunification of Taiwan in the most extreme cases. Even though this was less likely, it still triggered the involvement of the United States in China-Taiwan relations by sending two aircraft carriers into the Taiwan Strait, which acted as a deterrent against an escalation in violence.

After that, China’s conciliation with Taiwan entered a frozen stage. At that time, China’s comprehensive national and military power was still limited, so it could not launch a direct war against Taiwan without regard to other matters, and China lacked certainty in this regard. Deterrence strengthened China’s linguistic claim to further sovereignty over Taiwan in response to the Taiwan Teng-hui Lee government’s increasingly obvious tendency towards Taiwan independence. Based on this policy lead, Mainland China has reduced its release of goodwill toward the Taiwanese side because, based on the past decades, conciliation has not strengthened the island’s leadership and popular expectations for peaceful cross-strait unification, but rather has promoted the development of independent forces in Taiwan. So, Mainland China’s

late attempts to deter Taiwan’s leadership and population, including by military means, have in fact further damaged relations between Mainland China and Taiwan. But this was clearly a choice which had no choice; Mainland China in fact acquiesced to Taiwan’s de facto independence, but at the same time drew a line in the sand to maintain the status quo for Taiwan – “the day Taiwan declares independence is the

day Mainland China will reunify by force of arms”.

4. Hujintao’s China–Deterrence to Conciliation

Hu Jintao, the first Communist Party of China (CPC) leader after the institutionalization of the succession of the CPC leaders, was more open-minded overall, but did not dramatically change cross straight relations, choosing to carry over policies. At the beginning of Hu Jintao’s tenure, as China had just joined the WTO, the overall tension was not as strong as it had been during the 1996 Taiwan Strait crisis, although the deterrence strategy continued. As the pro-independence tendency of the Chen Shui-bian government became increasingly obvious, Hu Jintao used legal means to strengthen the Taiwan policy, which also indirectly reflected Hu’s legal thinking and concept. In 2005, China’s “Anti-Secession Law” clearly stipulated if the Taiwan authorities took “major incidents of splitting the country”, the Mainland could take “non-peaceful means and other necessary measures” to maintain national unity.

In 2008, Taiwan completed its second post-war election, with the Kuomintang (KMT) regaining power and the new president Ma Ying-jeou once again recognizing the 1992 Consensus, which provided the basis for Mainland China’s policy toward Taiwan to return to conciliation. Hu further promoted cross-Strait economic, trade and cultural exchanges during his tenure, and pushed for the signing of the Cross-Strait Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA). His Taiwan policy is more inclined towards peaceful reunification, emphasizing win-win situations through cooperation.

5. Xijinping’s China–The Great Power Coming Back

In 2012, Xi Jinping, the scion of a prominent red family, became the fifth- generation leader of the Communist Party of China (CPC). During the early years of Xi’s rule, from 2012-2016, the Kuomintang (KMT)’s Ma Ying-jeou government continued to govern in Taiwan, maintaining a relatively stable relationship between the two sides. Both sides pushed for the signing of The Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA), although it did not materialize. For the first time since 1949, the leaders of the two sides met in 2015: the tone of the meeting was friendly and cordial.

It appeared as if a continuation of the position of negotiations from the previous 40 years was possible. In 2016, Tsai Ing-wen of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was elected as Taiwan’s leader. She has led the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) through the past few years in a grueling and ultimately successful effort to continually reform and win over the support of the Taiwanese people. Since Ing-wen’s election, over the past eight years, the relationship between the Taiwan authorities and the Mainland China authorities has not been bad, but it has been complicated by the US’s regional policy. The Obama administration’s proposed Asia-Pacific rebalancing strategy has resulted in China being put increasingly under the spotlight.

The geopolitical situation in the Asia-Pacific has also hardened with several of countries changing governments to those less friendly with China: Moon Jae-in coming to power in South Korea, Duterte in the Philippines, Vietnam’s Nguyen Phu Trong consolidating his power, and even Indonesia’s Joko pursuing a more balanced policy between China and the United States. All of this is based on the growth of China’s power and the international profile that China has largely maintained since its reform and opening up, but more realistically, of course, because of the financial benefits that China has been able to provide to these countries. With issues including occupation and ownership of areas in the South China Sea and the Diaoyu Islands, the world has developed a hardened stance against China’s position on Taiwan.

Donald Trump’s new administration further isolated China. The Chinese government continued to bet on Clinton in the 2016 election, believing instead of supporting an unpredictable populist leader, it would be better to continue to deal with the Clintons, a Democratic Party establishment candidate which it knows well and has more ties to China. But Beijing miscalculated; Trump’s election changed the entire geopolitical landscape of the Asia-Pacific region for the future of Xi’s second term. Perhaps because the Chinese side is fully betting on his rival, or perhaps because, as a businessman, he saw the threat of China and the damage it is doing to American business and industrial interests, China became Trump’s first target.

Given the hardening of other governments and the U.S, tensions heightened further with the Tsai Ing-wen government. Although it did not declare independence, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government’s refusal to recognize the 1992 Consensus and the non-affiliation of the two sides of the Taiwan Strait caused China to change its policy towards Taiwan from conciliation to deterrence, and in the following years.

In years which have followed, diplomatic exchanges and progress towards unification between China and Taiwan have dropped to a low level. The Mainland China government has strengthened its military deterrence against Taiwan in general. This has included frequent, provocative, large-scale military exercises and the normalization of flights by military aircraft and warships around Taiwan. Politically, the slowdown in progress has meant the Taiwan issue is also increasingly in the international spotlight, with China continuing to “mine” Taiwan’s diplomatic relations and preventing Taiwan from exercising any form of power in international organizations.

In 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, altering the calculus for any possible resolution of the Taiwan issue by force. Russia’s poor battlefield performance has diminished the Chinese leadership’s confidence in recovering Taiwan by force. In August of the same year, Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan to further deter Mainland China from acting rashly and elevating the deterrence policy. But it her visit was considered to be provocative.

Under Xi Jinping Mainland China’s overall policy toward Taiwan remains under a policy of deterrence. The major difference between deterrence and coercion is deterrence has as its core objective “discouraging independence”, that is, acquiescing to the status quo across the Taiwan Strait, acquiescing to the fact of Taiwan’s existing political independence, and acquiescing to the notion of “one China” in the international arena, in order to minimize the cost of actual reunification. The core of the policy of coercion, on the other hand, is to “promote unification” and to promote cross-Strait unification regardless of the cost, which means that once it enters the stage of normalized coercion, war in the Taiwan Strait will be inevitable. However, such a situation has not arisen since 1949.

During Xi Jinping’s tenure, China has become more nationalistic and populist, while the Chinese people’s overall support for the Communist Party of China (CPC) government is high because of the country’s sustained rapid economic growth through 2022. According to a study by Harvard University’s Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, the Chinese people’s support for the Communist Party of China (CPC) government during Xi’s presidency has almost reached the historical peak of the modern People’s Republic of China.

But as Xi Jinping enters his third term challenges to the status quo are evident. The uncertain future of Mainland China’s economy is a cause concern for the governing power and restraint of the CPC; the election of Lai Ching-Te to the presidency of Taiwan, where the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a more pronounced tendency to be independent; the gradual convergence of Western policies toward China after the Russo-Ukrainian War; the unstable geopolitical situation in Southeast Asia, with the drastic change in the political arena in Vietnam, the new government of the Philippines turning fully toward the U.S., the new and unpredictable president in Indonesia. All of these represent a series of problems which have prompted Xi Jinping’s government to make tough decisions, but the international situation and the deterioration of China’s international image in the past five years raises the challenge to the maintenance of peace.

II. History and Analysis of Taiwan’s Policy toward Mainland China

1. History and Analysis

Taiwan’s policy towards Mainland China has roughly gone through a three-step phase from unification to independence to pragmatic maintenance of the status quo. Until October 1971, in Chiang’s family-controlled Taiwan’s politics, the one-party dictatorship of the Kuomintang (KMT) still retained the dream of retaking the Mainland, and for a long period of time Taiwan became the legitimate government representing all of China. And since most of the politicians in Taiwan’s politics at the time were expatriates (Mainland Chinese who evacuated to Taiwan with the Kuomintang (KMT), they still retained a desire to regain the mainland. So although the Kuomintang (KMT) government ruled only Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu for a long time, it still retained the basic position of unification. However, this unification is different from the basic concept of unification in today’s Taiwan politics, a unification in opposition to the Chinese communist government, a unification with the Republic of China as the main body after unification. Although the Kuomintang (KMT) still proclaims this today, everyone knows a compromise will be necessary.

In 1984, Lee Teng-hui was elected vice president and was seen as the successor to Chiang Ching-kuo, who was well aware of the hopelessness of the counter-offensive at the end of the Chiang dynasty. He went on to become Taiwan’s president in 1988 and led the country’s democratization and vindication of much of the government repression during the Kuomintang (KMT) dictatorship. Although Lee did not show a great tendency towards independence in the early years of his administration, he insisted on the idea of the unification of China by the Republic of China (ROC) on the one hand, and on pragmatic diplomacy to strengthen Taiwan’s non-Chinese presence on international occasions on the other, while also adopting the policy of “giving the Communist Party of China (CPC) a sweet date in return for a punch in the face” by criticizing China’s form of government, and on the other hand, negotiating with the Communist Party of China (CPC). However, after the 1996 Taiwan Strait crisis, Li Teng-hui’s political stance expression gradually formed into a more unique separate Taiwan consciousness.

As the Kuomintang (KMT)’s political rival, Chen Shui-bian of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) began his term in office by adopting a policy of independence against Lee’s government. The first was the “four no’s and one no’s,” which included not declaring Taiwan independent, not changing the country’s name, not promoting “two Chinas” or “one China, one Taiwan,” and not pushing for constitutional amendments to change the status quo, as well as not repealing the National Unification Program. This commitment eased Mainland China’s suspicions to some extent. He even considered accepting the 1992 Consensus in 2001 to improve cross-strait relations. However, the then head of the Executive Yuan’s Mainland Affairs Council, and later President Tsai Ing-wen, blocked this approach and persuaded Chen Shui-bian to continue the previous administration’s “special country- to-country relationship”, which was further amended to the “one country on one side” doctrine in 2002. Subsequently, the Chen Shui-bian administration shifted their view towards independence, pushing for “TAIWAN” to be added to the cover of passports in 2003, and putting forward the idea of “four musts and one must not be” in 2007, i.e., “Taiwan wants independence.” In 2007, he put forward the idea of “four things and one thing”, namely, “Taiwan wants independence, Taiwan wants a proper name, Taiwan wants a new constitution, and Taiwan wants development”. This was also the moment when the idea of independence was at its peak politically in Taiwan.

In 2008 with increasingly polarized policies, Taiwan completed its second peaceful party rotation, with the Kuomintang (KMT) coming to power, a sign of Taiwan’s political democratization. The core of President Ma Ying-jeou’s cross-strait policy is the “three no’s” – no unification, no independence, and no military force. Another way of describing the “Three No’s” policy is the “Muddling Through” strategy, which is the new core strategy of the Kuomintang (KMT) in the post-“counter-attack on the Mainland” era. The Kuomintang (KMT) recognized there is no hope for a counter- offensive on the Mainland, and also the “one country, two systems” proposed by the Communist Party of China (CPC) is not a political proposal acceptable to it or to all political groups except The Chinese Unification Promotion Party; it accepted “Muddling Through” as a solution, and even in some cases diplomatically stated that it “does not reject unification” and clearly opposed the idea of “legalistic Taiwan independence”. “Juridical Taiwan independence” and changing the name of the country to the Republic of Taiwan. And this is a more realistic strategy, seeking a balance between the United States and China, on the one hand, and the dual pressure of the United States and Mainland China, on the other, Taiwan’s international space is limited. Through “flexible diplomacy” and “peace initiatives”, he has sought to ease cross-strait tensions, reduce tension in the Asia-Pacific region, and at the same time please both China and the United States to maintain international support for Taiwan. However, at the same time, Taiwan has become more economically dependent on China, which has also damaged Taiwan’s ability to defend itself.

In 2013, Kuo Cheng-liang, then vice chairman of the pro-Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) media outlet Formosa E-paper, remarked that since the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)’s defeat in the 2012 presidential election, the party had not thoroughly reflected on the cross-strait challenges it faced and had never addressed the question of “why the U.S. is uneasy with the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in power.” He noted that “to this day, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)’s cross- strait narrative has not moved beyond the 1999 Resolution on Taiwan’s Future and the 2012 Ten-Year Policy Guidelines. Since these two documents failed to demonstrate in 2012 that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) could stabilize cross-strait relations and win the trust of both the U.S. and the Taiwanese people, it is even less likely that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) can rely solely on these documents to pass in 2016 as U.S.-China relations deepen.” Kuo further argued that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)’s refusal to accept the Constitution of the Republic of China and its ongoing entanglement with the idea of legal independence from China prevented the party from overcoming the “red lines” set by both the U.S. and China on cross-strait politics. As a result, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) could not convince the Taiwanese public that it could maintain cross-strait interactions, nor could it assure the U.S. that it could stabilize the legal status quo.

Although Kuo’s prediction for the 2016 Taiwanese leadership election did not

come true, he insightfully pointed out the dilemma the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was facing—its position risked increasing tensions between the U.S. and China. In contrast, the Kuomintang (KMT)’s muddling through policy appeared much more moderate and acceptable to both the U.S. and China. However, in recent years, U.S. support for the Kuomintang (KMT) has gradually diminished. One reason is that U.S. media often aligns with pro-DPP media in Taiwan to portray the Kuomintang (KMT) as being supported by the Communist Party of China (CPC). Another reason is the actual shift in public opinion, as the number of people supporting independence has grown. This is part of a broader trend since the beginning of the 21st century, which has seen the rise of populism and extremism.

With Ma Ying-jeou’s approval ratings remaining low in the latter part of his term, coupled with the internal strife of the Kuomintang (KMT) in the 2016 election and the negative impact of Hong Xiu-chu’s “rush to unification” policy, Tsai Ing-wen ran for a second term as president in 2016 and was successfully elected. She maintained the status quo of peace across the Taiwan Strait despite being the leader of the more independence loving Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Tsai pushed for the localization of Taiwan on the one hand, while seeing off the dual pressure from China and the United States on the other. She had the highest approval rating of any popularly and directly elected president in Taiwan when she left office. Unfortunately, the post-election position was disrupted by Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan.

In 2022, Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan was rendered in three different views by the mainstream media in the U.S., China, and Taiwan. The Chinese media reported Pelosi’s visit as a provocation, a demonstration against the unification of the motherland, and the clearest evidence of U.S. support for the two-nation theory. The Taiwanese media reported it as reflecting Taiwan as a true ally of the United States. If Taiwan is in trouble, the U.S. will definitely support it, and the visit also reflects the U.S. determination to deter China from protecting Taiwan. U.S. observers, on the other hand, saw it as a warning from Pelosi on behalf of the U.S. to both sides of the Taiwan Straits, but more in favor of Taiwan. At a time when Russia is invading Ukraine, the U.S. may not be able to provide all the support it needs if there is another war in the Asia-Pacific region, so Pelosi was asking Taiwan to exercise restraint and not to provoke Mainland China.

The different reactions of the three parties is reflected in the complex history of China. The CPC, on the one hand, sees the behavior of the United States and Taiwan through propaganda tactics, and on the other hand, propagates that the United States wants war in the Asia-Pacific region to undermine China’s long-term economic development. China’s propaganda department wants to put the blame on the United States for going to war or not going to war, so that, for China, if there is a war, the responsibility will be all on the United States side. Taiwan, on the other hand, is as conflicted as China in its desire for U.S. support for the cause of Taiwan’s independence as it is in its desire for the U.S. threat to counterbalance Mainland China. The core concern of the US is whether China is as vulnerable as Russia, and although the world considers the Russian army to be very corrupt, the US knows that it is still the third largest army in the world, and that any other country other than the US and China will not be able to fight at the same level as the Russian army, and will only fight worse. Ukraine is still able to maintain a stalemate with Russia because of the money and weapons power of the entire West, but if Taiwan goes to war at the same time, it will not be a risk the US can take. That’s why the US is eager to ensure ‘muddling through’ continues.

Despite the desire of some Taiwanese citizens and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to pursue independence, no one is willing to pull the trigger—whether it be the U.S., China, or any political forces or citizens within Taiwan.

2. 2024 Election and Future

Taiwan’s election in 2024 was ultimately a full three party race. This is different from the previous situation of two strong parties and one weak party, in which all

three parties and candidates have established their own core voter base. In addition to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the Kuomintang (KMT), the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), a new political party established in 2019, has at its core former Taipei mayor and physician Ko Wen-je, who was later joined by former legislator and leader of Taiwan’s Sunflower Student Movement, Huang Kuo-cheong. The main supporters of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) are young people who are opposed to both the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the Kuomintang (KMT), who advocate Taiwan’s autonomy and cross-strait peace, and who are less inclined to independence than the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), and more inclined to the status quo. Polls at the time of the election determined an almost certain victory for

the Kuomintang (KMT) over the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) if it cooperated with the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP). However, a final dispute between the two parties over the method of deciding on a presidential candidate resulted in both parties maintaining their decision to run independently in the end. The cross-strait relations policies of the three parties have basically not departed from the basic condition of maintaining the status quo: that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is more in favor of unification and the Kuomintang (KMT) is more in favor of maintaining peace.

The loss of the Kuomintang (KMT)’s cooperation with the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and the fact that the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) is still shallowly rooted led to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)’s successful reelection. The new president, Lai Ching-Te, is seen as one of the more radical Taiwanese independence activists in the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), and vice president Hsiao Mei-Chin has also served as Taiwan’s representative to the United States. However, the number of voters who do not support the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is about 60 percent, reflecting voters’ skepticism that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) could lead Taiwan to war. Whether or not Lai declares Taiwan’s independence during his term of office will be an important indicator of whether or not the Mainland China confirms the escalation of its deterrence policy to coercion policy. However, suppose China does not pursue armed unification of Taiwan. In that case, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) will have a long-term voting advantage unless the Kuomintang (KMT) populizes or combines with the People’s Party to make a leftward shift, but this would also mean that the Kuomintang (KMT) would have to blur further the “1992 Consensus” and the “one-China” principle. This also means that the Kuomintang (KMT) has to blur the “1992 Consensus further” and the “One China” principle and promote localization, not to reunify the Republic of China with China but to maintain the status quo forever as its core strategy. No matter how this will also affect Mainland China’s decision-making. The Kuomintang (KMT)’s current ambiguity in cross-strait relations is, to a certain extent, a preparation for armed unification. Lien Shengwen, vice chairman of the Kuomintang (KMT) and son of Kuomintang (KMT) patriarch Lien Chan, is seen as the most pro-Beijing Kuomintang (KMT) official and, assuming armed reunification, may be an excellent candidate to be the chief executive of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on Taiwan.

3. People’s Choice

Based on a study by Election Study Center, National Chengchi University. The distribution of Taiwan people’s political party preferences showed a strong correlation with the distribution of Taiwanese/Chinese identity and the stance on unification and independence.

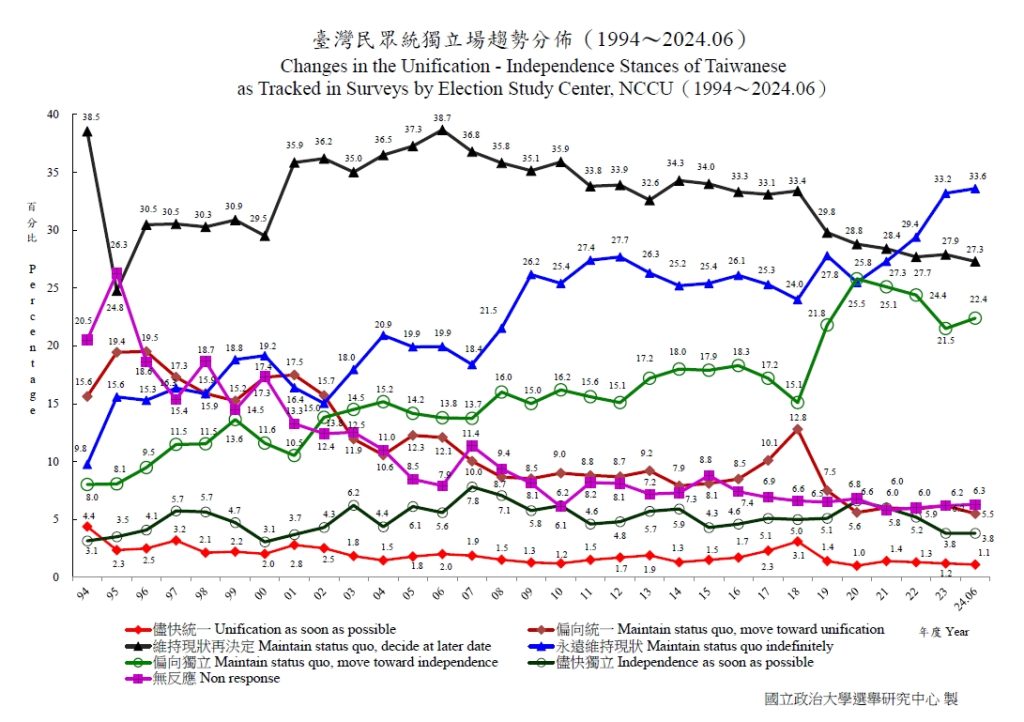

Starting from the unification and independence stance, the proportion of Taiwanese people who maintain the status quo and favor independence has grown over the past 30 years. Among them, maintaining the status quo has grown from about 40% to nearly 60%. Those favoring independence grew from less than 10% to more than 20% over the same period. Overall, these two categories account for more than 80% of Taiwan’s population today. Those who favor reunification or reunification as soon as possible has dropped from just over 30% to less than 10%. At the same time, it is important to specifically point out that the proportion of people supporting the permanent maintenance of the status quo has risen from less than 10% to nearly 35%. This represents the most significant shift in Taiwanese perceptions regarding unification and independence.

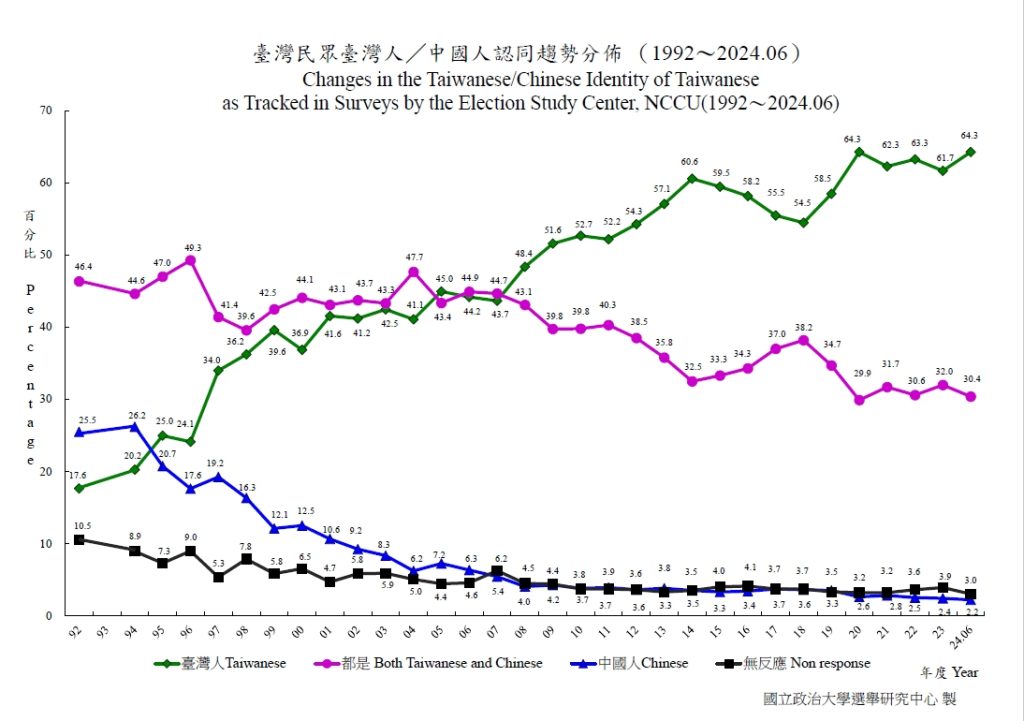

The change in Taiwanese identity has been the most notable of all statistics presented. 30 years ago, the number of those self-identifying as Taiwanese was less than 20%, but in 2024, it is already more than 60%. At the same time, those who identified as both Chinese and Taiwanese dropped from around 50% to around 30%. It’s just the Chinese who have dropped from about 25% to negligible.

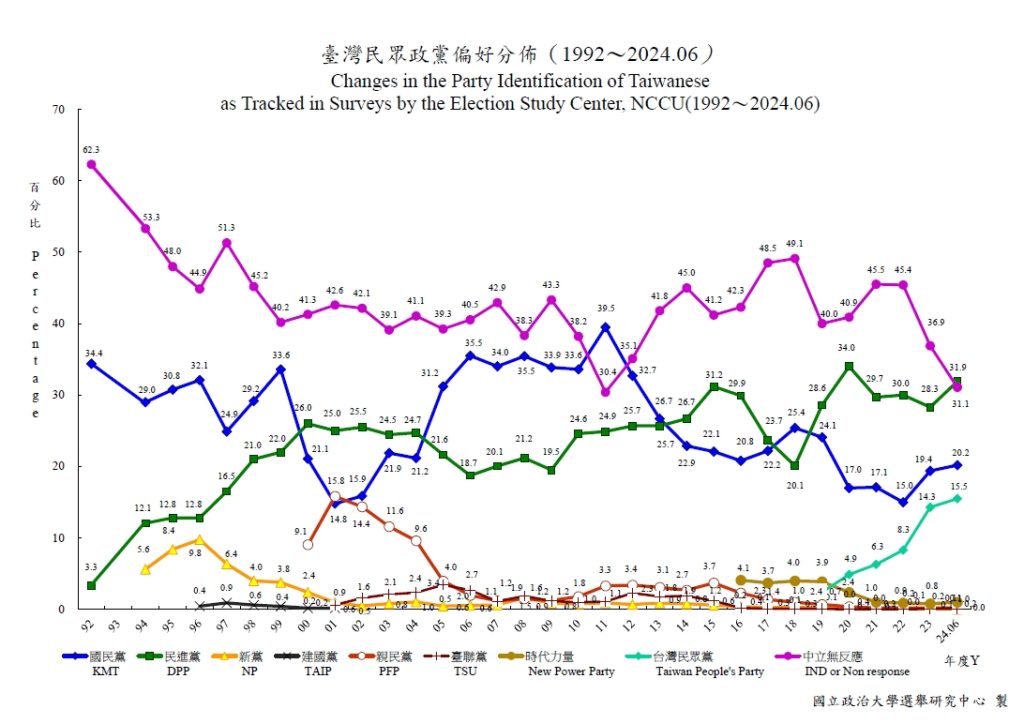

There is also a big change in party leanings, with neutral or independent identifying voters dropping from over 60% to around 30%, and the Kuomintang (KMT)’s approval rating fluctuating from around 35% down to a low of around 15% when Lee Teng-hui left office, to a high of close to 40% in Ma’s first term, and then a steady decline since then to around 20% today. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), on the other hand, has maintained an overall upward curve, from 3% to 30%. The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) has seen its support rate rise from less than 1% to more than 15% in the five years since the party’s founding creating a true three way party split with a about 30% of voters switching between the parties. .

When analyzed comparatively, a few trends are notable: it is evident that the downward trend in the number of individuals who are neutral or unresponsive in terms of political party preference aligns closely with the declining trend of those who identify as both Chinese and Taiwanese.

Conversely, the upward trend in support for the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) corresponds closely with the increase in individuals who identify solely as Taiwanese and those who favor Taiwan’s independence. Correlation suggests this is connected to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)’s stance on Taiwanese independence. However, despite this, we consistently see note the proportion of those pushing for immediate independence or leaning towards it remains far lower than those who prefer to maintain the status quo (26.2% vs. 60.9%). The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ‘s core support likely comes from the 26.2%, while the remaining supporters are less stable.

It seems the rise in Taiwanese identity and the significant growth in support for permanently maintaining the status quo reflects the sentiment among Taiwan’s younger generation, particularly those who have grown up after the relatively stable cross-strait relations that followed the 1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis. This generation is not inclined to go to war but also does not want independence. A survey released by Taiwan’s Global Views Monthly in January 2022 showed that if war were to break out between Taiwan and Mainland China, 51.3% of the public would be unwilling to go to the battlefield themselves or send their family members, with only 40.3% willing to do so. Among those aged 20 to 29, the percentage unwilling to fight is the highest, reaching 70.2%.

After analyzing all the data, it is again possible to identify certain specific points in time and events that influenced the decisions of the Taiwanese people. For example, the Hong Kong Protests in 2019 gave a steep rise in the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP)’s support; these voters are Taiwan independence supporters who solely identify as Taiwanese and responded to the failure of the administration.

Overall, the degree of division within Taiwanese society is significant, but it is not as absolute as in the United States. Compared to social issues, the divisions in Taiwan are more focused on government performance, external factors, and the highly sensitive cross-strait relations. This has resulted in Taiwanese politics being more susceptible to external influences. The question then arises: if war were to come, would Taiwanese people be able to defend their land like the Ukrainians? Would the cost to China of reunifying by force not be worth it for the Taiwanese. At least from the data, this seems challenging.

III. Cost Benefit in the Long Run with Invasion

1. Economics Factor

Contemplating an invasion of Taiwan is difficult, but it is possible to model the costs and benefits of such an invasion and understand what might happen. Looking first at the economic situation, China has recently weakened economically. Before 2019, China’s rapid economic growth was considered a global miracle. The Communist Party of China (CPC) saw this as, and in fact it became, its primary source of legitimacy—the massive success of China’s system under CPC leadership. However, since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, several economic and social governance issues have emerged. The traditional “three driving forces” of Chinese economic growth in China are now all in decline

First, due to China’s overcapacity and insufficient domestic consumption, exports became a key factor in maintaining economic growth in the 2000s. However, as major export destinations like the United States and the European Union applied political pressure and protectionist trade measures against China, exports ceased to be a significant driver of China’s economic growth. The decline in exports has led to difficulties for millions of Chinese blue-collar workers, and small factory owners have become some of the most economically vulnerable groups in Chinese society.

Second, a significant portion of economic growth, especially in real estate and infrastructure investment—once the backbone of the economy—was funded by massive loans from property developers and local government hidden debt financing (known as municipal investment bonds). While these actions previously generated vast wealth and development for China, they now must be paid back and because incomes have stalled paying these loans back is finically very difficult. Since 2021, with the debt defaults of landmark real estate companies like Evergrande, the era of real estate and infrastructure driving China’s economic growth has collapsed. Similarly, following the pandemic, foreign investment in China has decreased, with many investors withdrawing their funds from the country. Domestic investment institutions in China have also faced difficulties in raising funds, making it hard for startups to survive. Now, only companies aligned with China’s governmental development strategies, such as those in semiconductors and artificial intelligence, are likely to secure funding. The rapid decline in the number of newly established unicorn companies each year and the overall decrease in financing reflect that this second economic driver is no longer effective.

Third, with the impact of the first two factors and the general pessimism about future economic and political development, consumption levels in China have also been weak. While wealthy individuals continue to shop in high-end luxury stores, a majority of people believe saving their money in banks is the safest option. All three driving forces have stalled, and within five years, China’s economy has fallen from its steep upward trajectory and is now teetering.

2. Military Factor

Beyond the economic struggles, Taiwan indeed remains a challenging place for military action and here again, it seems difficult for China to succeed. First, the Taiwan Strait, which separates Taiwan from Mainland China by about 180 kilometers, has complicated maritime conditions, and the large number of commercial vessels make it difficult to create a fully controlled battlefield without advance notice, preventing the possibility of a surprise attack. Additionally, any amphibious landing in Taiwan must be conducted on its western coast, where landing points are very limited. The Taiwanese military can easily pre-position sea mines at ports and landing sites, significantly hindering the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) operations. Moreover, Taiwan’s rugged terrain would allow Taiwanese forces to replicate the guerrilla warfare tactics used by the Communist Party of China (CPC) during the Chinese Civil War and the Anti-Japanese War, potentially inflicting heavy casualties on the PLA.

At the same time, the potential involvement of third parties is also a crucial consideration. While the likelihood of direct intervention by the U.S. and Japan in a conflict is low, actions such as airlifting ammunition and weapons to Taiwan, maintaining a presence on the battlefield to help Taiwan monitor the movements of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and other similar support measures could result in accidental involvement in the war.

3. Sanctions

There can be no doubt about China’s ability to militarily defeat Taiwan. At the same time, I do not believe that the so-called “blockade strategy” would be effective. On the issue of sanctions, China’s strategy is to hold the West, particularly Europe, economically hostage, and this strategy has a far greater chance of success than Russia’s. However, from the perspective of how the West might respond, if we assume China is determined to recover Taiwan by force, the best way to mitigate the risks would be to continue a firm process of “decoupling” from China, spreading the inflationary impact over the coming years. Yet, this seems unrealistic. The U.S. is in an election year, and the Biden administration is eager to smooth its path to reelection, has focused on reducing inflation, which led to an increase in U.S. imports from China in the first half of this year. Thus, “decoupling” appears at odds with the current political realities. China, with its long-term one-party rule, does not face such pressures.

The effectiveness of potential American sanctions is worth considering. China’s annual trade volume with the EU and the U.S. exceeds $1.5 trillion. No matter how much countries push for “decoupling” from China, it’s impossible to eliminate such a large amount of trade within just a few years. Industrial relocation is a long process, not one that can be driven solely by political will. If the goal is to cut the volume of trade in half, and it is possible to reduce trade by 10% per year, it would take until 2031 to reach the goal, which is certainly later than the 2027 “deadline” many scholars predict as China’s potential last opportunity to take Taiwan by force. While I am not a supporter of this “last deadline,” if the downward trend in trade is already established, China might be more motivated to attack Taiwan. In other words, when China believes the value of recovering Taiwan outweighs the value of maintaining U.S.-China or China-EU relations, it will make the decision to take Taiwan by force, and vice versa.

Of course, the above perspective is influenced by other factors. First, I don’t believe that the West and China can reduce trade by 10% per year. Especially in the case of China-EU trade, China’s grand strategy is quite clear—maintain absolute alliances with countries like Russia, Iran, Syria, and North Korea; cultivate close relationships with valuable Belt and Road countries like Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, and Indonesia; and adopt a strategy of friendliness toward Europe while responding firmly to specific actions (mainly countering certain European policies). Europe holds more leverage than China, and it is still under the influence of the United States, as evidenced by Ursula von der Leyen acting as a U.S. proxy, showing the U.S. continues to wield significant influence in Europe.

This suggests significant rifts could emerge among Western nations when it comes to sanctioning China. Some countries might opt for relatively symbolic actions, like freezing Chinese officials’ assets in their territories. On trade, recent developments show Germany and Spain putting pressure on the EU to reconsider imposing additional tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, illustrating the deeply divided views on China within the EU. In specific cases, national interests lead to differing opinions— for instance, Germany opposes tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles to protect its luxury car sales in China, while France, with a weaker automobile industry, supports the tariffs.

In this way, the economic entanglement between the West and China differs greatly from that with Russia. The West’s economic ties with Russia were insufficient to prevent them from imposing significant sanctions on Russia in exchange for safeguarding their interests. Russia initially sought to leverage its oil and natural gas to hold Europe hostage. This strategy unsettled Europe at first, but as the U.S. and Middle Eastern countries increased their oil and gas supplies to Europe, the crisis was averted. However, the interdependence between China and Europe is different. The ties between Russia and Europe could be severed because substitutes were available. But there is currently no alternative to China’s industrial production capacity. If the price of toilet paper in Europe rises to €10 per roll, such sanctions would inevitably backfire.

In summary, if China and Taiwan go to war, the severity of American and European sanctions will depend on China’s performance on the battlefield and whether the West can firmly commit to decoupling from China over the next few years. Otherwise, the sanctions could backfire on themselves.

4. International Factors

Whether China can gain sufficient support or neutrality from the international community is a key factor in the war. China has consistently emphasized the Taiwan issue is a matter of its domestic affairs, distinguishing it from the Russia-Ukraine conflict or the Israel-Palestine issue. However, several Western countries have recently pushed for a reinterpretation of the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2758. The U.S. Congress passed a bill stating that “Resolution 2758 only addresses the issue of China’s representation, and does not involve Taiwan.” Similarly, an Australian parliamentary bill claims that UN Resolution 2758 “does not establish the People’s Republic of China’s sovereignty over Taiwan, nor does it determine Taiwan’s future status in the United Nations.”

If a resolution similar to the one condemning Russia’s “illegal annexation” in Ukraine were to be presented at the UN regarding Taiwan, how might the vote play out? First, China would likely receive more votes in favor than Russia or Israel, but the “In Favour” votes would still be an absolute minority. Some Southeast Asian, Central Asian, and African countries might vote in favor, along with perhaps Russia (even though China abstained on the vote regarding Russia’s actions). However, many countries would likely abstain, and the number of abstentions would be much higher than those seen in votes involving Russia and Israel. Ultimately, Western nations, along with Japan, South Korea, India, Australia, and New Zealand, would likely lead the opposition. To gauge whether China has sufficient international support, we would need to look at the combined total of “In Favour” and “Abstention” votes and see if this surpasses the “Against” votes. Given the expected large number of abstentions, such a resolution would likely pass, resulting in a formal condemnation of China and possibly even demands for China to withdraw from Taiwan.

However, since this type of resolution carries no legal weight, China would likely not be overly concerned. International bodies like the United Nations would probably adopt a neutral stance, refraining from taking a strong position. The most important factor in this situation is the attitude of Southeast Asian and Middle Eastern countries. Take Vietnam as an example—it could potentially vote “In Favour,” “Abstain,” or “Against.” If countries like Vietnam vote against China, it would indicate that they have lost confidence in China’s future and do not believe that China can outcompete the West in the long term. A vote of abstention would suggest these nations anticipate China facing greater international pressure, but it can still maintain a regional presence. A vote “In Favour” would demonstrate that Vietnam’s leadership believes China will eventually replace the U.S. as the dominant power. The stance of other Belt and Road Initiative countries would similarly reflect their optimism toward China, and by extension, their expectations for the outcome of a potential conflict.

Regardless of how the votes turn out, China’s international image would undoubtedly suffer. However, the actual impact on China’s global standing would be limited. These votes would serve more as a barometer for assessing how other nations perceive China’s future and its prospects in the global arena.

IV. Conclusion

The Taiwan Strait has maintained peace for nearly 80 years, but the Communist Party of China (CPC)’s desire to reunify Taiwan has never waned with time. Whether peaceful unification is possible and if this peace can continue beyond 80 years is a multi-dimensional issue, encompassing domestic, international, economic, livelihood, and public opinion factors. With the changing geopolitical landscape in recent years, the tension in the Taiwan Strait today is at an all-time high and continues to escalate. The future of Taiwan remains uncertain.

Data Collection Methodology

I. Data Sampling and Analysis

The research target population for each survey is the adult population 20 years or older in the Taiwan Area (i.e. excluding the offshore islands of Kinmen and Matsu). Sample for every landline phone survey is drawn from telephone books, with the most recent year’s set of China Telecom Residential Telephone Number Books serving as the population. Each sample is constructed from numbers listed in each county and city telephone book and is drawn proportionately from all residential phone numbers across the island. In order to ensure complete coverage, after systematic sampling produces a sample for each city and county, it is then supplemented as circumstances warrant based on the last one or two or three or four digits to include households with unlisted numbers. After phone contact is established, the interviewer follows the specified intra-household sampling procedure to identify the targeted member of the household, and begins the interview.

The mobile phone survey is based on the “Mobile Communication Network Business User Number Allocation Status” published by the National Communications Commission (NCC) (the allocation status of the first five digits of the mobile phone number), combined with randomly generated codes/numbers representing the last five digits of mobile phone numbers to create the phone sample.

In order to ensure that the sample structure is more representative of the population, key sample variables are used to weight the sample’s partial characteristics through an iterated (raking) process. These include weights for sex, age, education and geographic location calculated from the Taiwan-Fukien Demographic Fact Book, Republic of China, published by the Ministry of the Interior.

The chart of trends in core political attitudes among Taiwanese is based on data gathered through this center’s telephone survey polls. Survey data is merged annually to generate data points, except those released in June; they come from surveys conducted between January and June. After results are weighted, the figures for the three main variables are parsed out and added to the trend chart. Percentages are rounded to the nearest tenth, so the total of the percentages may not be 100%.5

II. Time of Coverage and Sample Sizes

The data presented in the current trend chart includes that from 1992 through the first half of 2024. The interview sample sizes for each year are detailed below:

Year Cases

1992 4120

1994 1209

1995 21402

1996 10666

1997 3910

1998 14063

1999 9273

2000 11062

2001 10679

2002 10003

2003 14247

2004 34854

2005 7939

2006 13193

2007 13910

2008 16280

2009 20244

2010 13163

2011 23779

2012 18011

2013 13359

2014 20009

2015 22509

2016 15099

2017 13455

2018 9490

2019 16276

2020 11490

2021 12026

2022 12173

2023 14933

2024 61516

III. Main Variables

1. Taiwan Independence versus Unification with the Mainland (TI-UM) The independence-unification (TI-UM) position is constructed from the following survey item: “Thinking about Taiwan-mainland relations, there are several differing opinions: 1. unification as soon as possible; 2. independence as soon as possible; 3. maintain the status quo and move toward unification in the future; 4. maintain the status quo and move toward independence in the future; 5. maintain the status quo and decide in the future between independence or unification; 6. maintain the status quo indefinitely. Which do you prefer?” In addition to these six attitudes, the trend chart also includes non-responses for a total of seven categories.

2. Political Party Identification (PID)

The political party identification variable was constructed through the following steps. The respondent is first asked the following: “Among all political parties in our country, which party do you think of yourself as leaning toward?” If the respondent does not answer unequivocally, then s/he is asked “Relatively speaking, do you lean toward any political party?”. If the respondent then names a party, that answer is taken to be his/her party ID; and if the respondent still does not indicate a preference, the answer is counted as a non-response and others.

3. Taiwanese Identity

The following survey item was used in all instances to construct the measure of Taiwanese identity: “In our society, there are some people who call themselves ‘Taiwanese’, some who call themselves ‘Chinese’, and some who call themselves both. Do you consider yourself to be ‘Taiwanese’, ‘Chinese’, or both?”. Responses are scored into one of fourcategories: Taiwanese, Chinese, both, or no response.

Statement of Copyright

The contents displayed on this website, including but not limited to text, figures, formatting, audio and visual recordings, and other information, are without exception protected by copyright. Under copyright law, materials on this website can be downloaded for private use, under the condition that the user includes the following acknowledgement: “Source: Core Political Attitudes Trend Chart, Election Study Center, National Cheng Chi University.” This webpage may not be reproduced in part or in full without permission of Election Study Center. Without express approval, this website or any part of its contents may not be reproduced, broadcast, presented, performed, transmitted, modified, disseminated or used in any other activity covered under the standards of current copyright law. Actions taken in proper accordance with copyright law are not subject to this restriction.

Works Cited

Chao, Linda, and Ramon H. Myers. The First Chinese Democracy: Political Life in the Republic of China on Taiwan. John Hopkins University Press, 2003.

Copper, John F. Taiwan: Nation-State or Province? 5th ed., Westview Press, 2008. Dittmer, Lowell, ed. Taiwan and China: Fitful Embrace. University of California Press, 2017.

Hickey, Dennis V. Foreign Policy Making in Taiwan: From Principle to Pragmatism. Routledge, 2006.

Shambaugh, David. China and the World. Oxford University Press, 2020.

Tucker, Nancy Bernkopf. Dangerous Strait: The U.S.-Taiwan-China Crisis. Columbia University Press, 2005.

Nathan, Andrew J., and Andrew Scobell. China’s Search for Security. Columbia University Press, 2012.

“Taiwan Relations Act.” Public Law 96-8, 96th Congress of the United States of America, 1979. U.S. Government Publishing Office, www.govinfo.gov.

United States Department of Defense. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022. Office of the Secretary of Defense, 2022, www.defense.gov.

Chen, Dean P. U.S.-China Rivalry and Taiwan’s Mainland Policy: Security, Nationalism, and the 1992 Consensus. Springer, 2017.

United Nations. Resolution 2758: Restoration of the Lawful Rights of the People’s Republic of China in the United Nations. General Assembly, 1971. United Nations Digital Library, digitallibrary.un.org.

About the author

Bill Wu

Bill Wu is a high school student in the U.S. with a keen interest in political science, focusing on American and Chinese politics. He is active in leadership roles, including as Secretary-General of his school’s Model UN, and is the founder of an AI education startup named XStudy AI. His work aims to bridge cultural gaps and contribute to global political discourse.