Author: Tengyu Cui

Beijing National Day School

Abstract

This paper assesses the introduction of tomatoes to China and the environmental and economic factors that influenced their adaptation. Based on historical and agricultural data, the study identifies two primary routes through which tomatoes entered China: the Heilongjiang route in the north and the Guangdong route in the south. The evolutionary progression of the two tomato varieties is influenced by regional differences in climate types and soil fertility. In northern China, lower temperatures and significant day-night temperature variation promoted carbohydrate accumulation, resulting in the cultivation of Pink Fruit Tomatoes (PFT) with a higher extent of sweetness. In contrast, the warmer southern climate favored the synthesis of red pigments, leading to the development of Red Fruit Tomatoes (RFT), which contain fewer carbohydrates. The paper also highlights how the dissemination of tomatoes influenced local dietary preferences and led to agricultural and economic growth. These findings underscore the importance of ecological factors in crop adaptation and demonstrate the broader cultural and economic impacts of tomato cultivation in China.

Keywords

Solanum lycopersicum, tomato, China, food science, environment, climate, potassium content, cuisine history.

Introduction

Can you imagine a world where people consume food made of bland chemical compounds? Can you imagine the world that we live in without the existence of crops? Crops are indispensable for the development of human civilizations. Many crops were introduced to China from exotic regions [1]. One of China’s most significant exotic crops is tomato (Solanum lycopersicum).

The tomato is believed to have originated in the Andes Mountain region. Specifically, the ancestor of wild-type tomatoes (S. pimpinellifolium) was thought to have first originated from Peru. In contrast, the ancestor of the cultivated tomatoes (Lycopersicum esculentum var. cerasiforme) was considered to have first originated in Mexico. There are three subgroups of tomatoes: small (S. pimpinellifolium), moderated (S. lycopersicum var cerasiforme), and large (S. lycopersicum). They differ in economic values, are suitable for domestication, and have a wide cultivation scope [2].

History records and sequencing analyses suggest that tomatoes were introduced to China in the Ming Dynasty, around the 17th century. In addition, historical recordings indicate that tomatoes were reintroduced during the early period of the Republic of China. The general communication routes by which tomatoes were introduced to China can be classified into two relatively late-diverging pathways.

In the first route, tomatoes were introduced to the Philippines and later cultivated there before being introduced to Guangdong Province and its vicinity. In the second route, Russians constructed the Chinese Eastern Railway and introduced tomatoes to Heilongjiang. The differences in latitude between these two regions led to changes in tomatoes as they adapted to their respective environments. Additionally, the genetic mutations arose due to the differing dietary habits of residents in various areas.

Specifically, S. lycopersicum has two subspecies in Heilongjiang and Guangdong. The Heilongjiang variant exhibits a lower level of expression of red pigments, which correlates with a reduced synthesis level of flavonoids in its peel. This characteristic makes it easier to peel the tomatoes, aligning with the dietary habits of residents in Heilongjiang. In contrast, the variant found in Guangdong has a normal synthesis level of flavonoids, resulting in a slight reddish peel. This adaptation benefits residents in southern areas where reliable sources of flavonoid intake are limited.

The characteristics that mainly affect the taste and the appearance of tomatoes are controlled by the fifth chromosome. There are several quantitative trait loci (QTLs) that control the hardness, total soluble solids, and other kinds of characteristics of tomato fruits that are related to the choice of species of tomatoes.

The variation in tomato species not only influenced cultivation practices but also led to significant changes in local economies and other aspects of society. The impacts of introducing tomato species can be explained from two different perspectives. This paper aimed to explore the reasons and genetic mutations that allowed tomatoes to thrive in China, the factors influencing their introduction, and the resulting economic and social impacts of these mutations in different areas.

Section 1

Introduction of Tomato to China

Species, characteristics, introduction

There are three major subgroups of tomatoes currently in the world. Among them, S. lycopersicum has the highest economic value for its flavor and nutrition [2], unlike the other two subgroups, S. pimpinellifolium and Lycopersicum esculentum var. cerasiforme. Specifically, the ancestor of wild-type tomatoes (S. pimpinellifolium) was considered to first originate from Peru, which has relatively small-sized fruit with a diameter of about 1 cm and mass of 1-2 g [3]. The ancestor of the cultivated tomatoes (Lycopersicum esculentum var. cerasiforme) was considered to have first originated in Mexico. This species of tomato has a diameter of about 3-8 cm and a mass of 10-30 g [3]. The most widely spread tomato species is S. lycopersicum, which originates from S. pimpinellifolium. It has more nutritious substances and flavor storage than S. pimpinellifolium, and it shows a higher potential of becoming an economic crop because it gradually approaches the standard. Because of these characteristics, Mexicans began to domesticate tomatoes relatively early. After Columbus discovered the New World, the tomato spread to a more extensive range than the rest of the world. In the Mid-16th century, the tomato was introduced to Europe; in the 17th century, the tomato was introduced to Filipino; North America and Japan were shown that the tomato was introduced in the 18th century; the tomato stabilized its role for being a kind of global vegetable (economic crop) after 19th century followed by Miller first defined tomato botanically in 1768 [4]. The history of the tomato can be further explored in terms of how it was introduced in China, since it has been proven that it caused impacts. Two major regions where tomato was introduced in China were Guangdong, a southern province in China, and Heilongjiang, a northern province in China [5,6]. The species has the most abundant storage of nutritious substances and varied flavors, making it the species with relatively higher economic value among the three existing subgroups of tomatoes.

The route to Guangdong and its vicinity was introduced in the Ming Dynasty during the 17th century. Additional evidence proving that Guangdong was a region where the tomato was introduced is listed. First, in 1625, “Dian (Yunnan, an interior province close to Guangdong) Annals” mentioned that the tomato was introduced from Yue (Guangdong), meaning that in the Ming Dynasty, the tomato was introduced in Yunnan, following the introduction to Guangdong, indicating an earlier period that the tomato was introduced in Guangdong. Additionally, “Qian (Guizhou, an interior province close to Guangdong) Plants” mentioned the name of the tomato as “June Tomato” [7,8]. It is noteworthy that the writer of “Qian Plants” had taken office in Guangdong [5], proving that the origin of the introduction of tomatoes to China was in Guangdong.

Meanwhile, Heilongjiang and its vicinity also introduced tomatoes in the early period of the Republic of China [5]. In 1915, 1930, and 1932, the “Hulan County Annals” [9] and the “Heilongjiang Annals Collection” [8] gave descriptions of tomatoes introduced there with similar descriptions of S. lycopersicum and mentioned that the tomato was introduced from Russia, indicating the Russian origin of the tomato in the northern route. Also, Russia constructed the Chinese Eastern Railway, which propelled the prosperity of Harbin [10]. During this period, Russia also brought seeds as food to northern China.

Section 2

Environmental factors that affect the introduction of tomato

Several environmental factors can affect the introduction of tomatoes because different subspecies of tomatoes require different environments to survive. This section of the essay will focus on three environmental factors: conditions of soil, conditions of climate, and the ability of tomatoes to adapt to the local environment. Because of the alteration of the environment, the tomato made some changes, including the differentiation of two subspecies, which are commonly called “Pink Fruit Tomato (PFT)” growing mainly in Heilongjiang, and “Red Fruit Tomato (RFT)” growing mainly in Guangdong.

Condition of the soil

The types of soil in Guangdong and Heilongjiang both allow it to be permeable to air and water [11, 12].

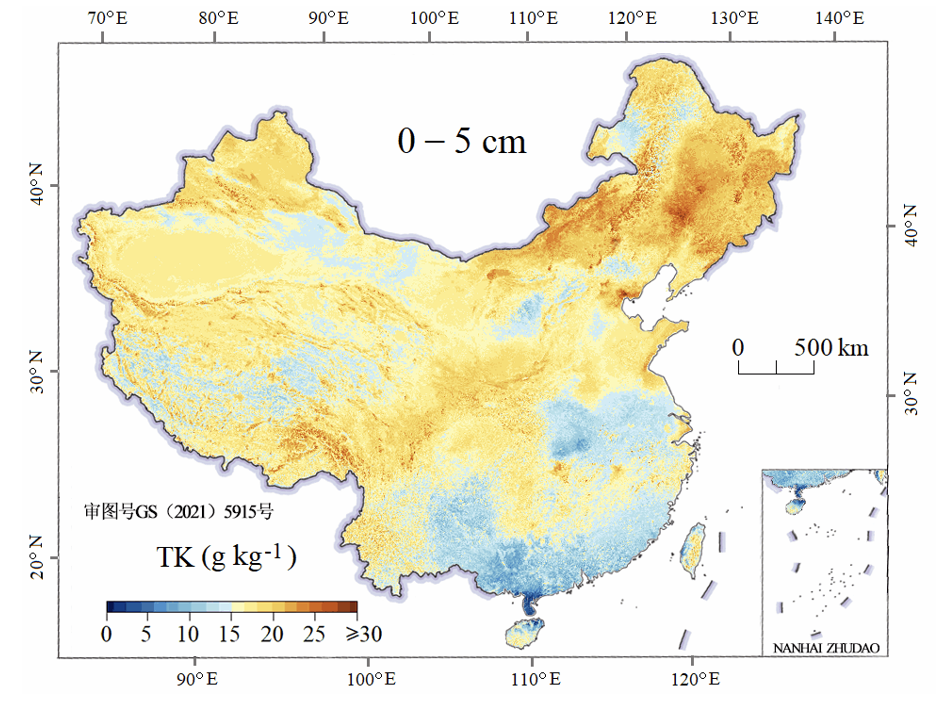

Figure 1 describes the distribution of potassium in the soil in China. The content of potassium is abundant in the plain in northern China, with total potassium greater than 25 g kg-1. This was formed by the accumulation of humus, since Heilongjiang has a warm spring and summer season and a cold, long winter season, making vegetation thrive in spring and summer and wither in winter. However, the formation of snow in the cold, long winter season makes it impossible to decompose the wasted plant tissues because the low temperature inhibits the activity of the microbes responsible for decomposing the tissues. With the repetition of this same process for millions of years, Heilongjiang finally formed a thick layer of black soil with an abundance of potassium and other kinds of nutrients.

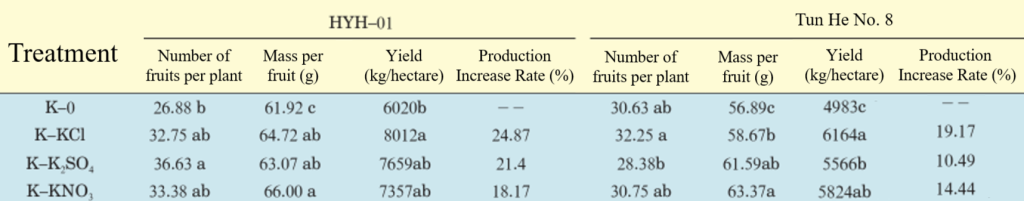

Figure 2 describes the relationship between the existence of addition of potassium on the growth of tomatoes and the final yield of tomatoes. It was shown that with the addition of potassium chloride, the yield of tomato is 8012 kg hm-2, which is higher than the group without the addition of potassium chloride with a yield of 6020 kg hm-2. These data suggest the ability of potassium to improve the yield of tomatoes; considering the data in Figure 1, it is suitable for the tomato to grow in northern China, especially the Northeastern Plain.

According to Figure 1, the soil condition in Guangdong does not show as excellent as in Heilongjiang because of the lower content of potassium. However, the strong adaptability of tomatoes to the local environment can compensate for this loss. If the basic requirement, such as soil with deep soil layers and good drainage, is achieved, the tomato can adapt to the environment without too much dependence on potassium. To be specific, the tomato requires high soil aeration, and when the oxygen content in the soil drops to 2% [15,16], the plants will wither and die. Therefore, it is not suitable to cultivate tomatoes in low-lying and poorly structured soils that are prone to flooding. Sandy loam has good permeability and a rapid rise in soil temperature, which can promote early maturity in low-temperature seasons. Clay loam or organic-rich clay with good drainage has strong fertilizer and water retention abilities, which can promote vigorous plant growth and increase yield.

Tomatoes are suitable for slightly acidic soils, with a pH of 6-7 [16]. However, the soil in Guangdong has relatively strong acidity, and it stores a high content of aluminum, which inhibits the growth of tomatoes. Tomato can withstand and survive is also caused of the resistance gene that can be activated by the high-acidity signal from upstream. Guangdong’s unique climate conditions allow tomatoes to adapt to nutrient deficiency, though harsh soil conditions include heavy metals and aluminum, unlike Heilongjiang’s high nutrient content. Granted, the high nutrient content in Heilongjiang allows the synthesis of more nutrients, such as soluble solids, but some colored substances including flavonoids and carotenoids may have a limiting synthesis because while the huge temperature differences between days and nights would favor the synthesis of sugar, the excessively low temperature might impede the synthesis of colored substances. Therefore, PFT would acquire a pink appearance and more content of sugar content, which is more compatible with the cuisine methods used by the Northern residents. Conversely, Southern residents prefer to cook food by stewing and boiling for a long time, and tomato fruits with excessive hardness enhanced by the absence of reaction between flavonoids and pectin in tomato fruits can withstand the condition, so the RFT becomes popular.

Condition of climate

In addition to the advantage of soil, Heilongjiang takes advantage of its climate conditions to be a great place for tomatoes to grow [11]. Heilongjiang is in the temperate monsoon climate region with relatively high rainfall and heat in summer and low temperature and relatively low rainfall in winter. The abundant sunlight and a huge gap in the temperature between days and nights lead to metabolic activity and storage of organic compounds in tomatoes [18].

Although the nutrients in the soil of Guangdong are limited, it still provides sufficient heat, rainfall, and sunlight because of its position in subtropical and tropical monsoon climate regions.

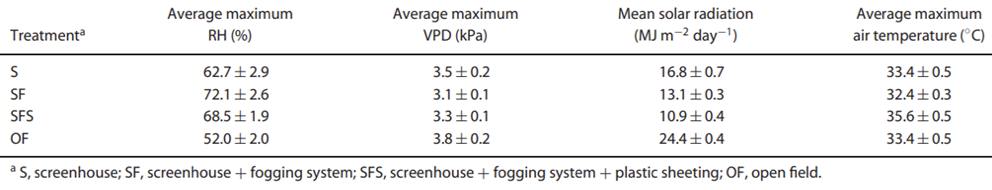

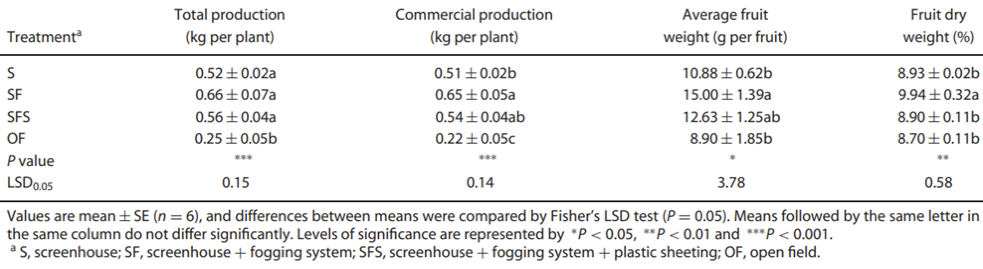

According to Table 2 and Table 3, Guangdong presents a high amount of precipitation [12,17]; another research about the impacts of relative humidity on the synthesis of nutrients of tomato fruits reveals that with the increase in relative humidity in the environment where the tomato grows, the activity of synthesis of nutrient increases, meaning that higher relative humidity will lead to a higher synthesis of nutrients, which sustains the survival of tomatoes, including flavonoids. This is caused by the variance that the 603 bp deletion in the promoter region of the SIMYB12 gene inhibits its expression, resulting in the inability to accumulate flavonoids in mature tomato peel [2].

On the other hand, low temperatures can activate the calcium ion signal in plant cells. This regulates the transcriptional activation of downstream cold signals and response factors. Calcium channel protein (CNGC) is believed to be involved in temperature sensing and response. One of the main known pathways for plants to sense low-temperature signals is through the ICE1-CBF-COR transcriptional cascade signaling. The ICE1 (inducer of CBF expression 1) gene encodes a bHLH transcription factor. After sensing the low-temperature signal, ICE1 directly binds to the promoter region of the CBF (C-repeat binding factors) gene to activate the expression of the CBF gene. This gene exists in tomatoes, which means that it can withstand the environment with low temperatures and survive [19]. The tomato, hence, will ignore the negative impacts caused by low temperatures, proving that Heilongjiang is an appropriate region to receive the introduction.

Mini Conclusion

In conclusion, the introduction of tomatoes to China can be attributed to the advantageous climate and soil conditions in Guangdong and Heilongjiang, while the adaptability of the tomato itself is also a possible reason that it can survive in regions that are extremely far away from its “homeland” — the Andes Mountains Region.

Section 3: Impacts of the introduction of tomatoes

The mentioned advantages and conditions of China propelled the introduction of tomatoes to China, and the introduction of tomatoes also made a difference in several aspects. The main impacts can be attributed to economic impacts and dietary impacts.

Economic impacts

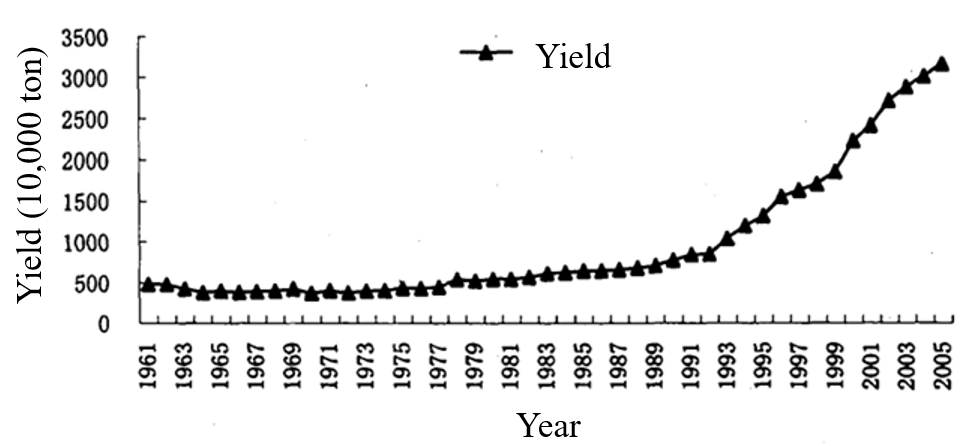

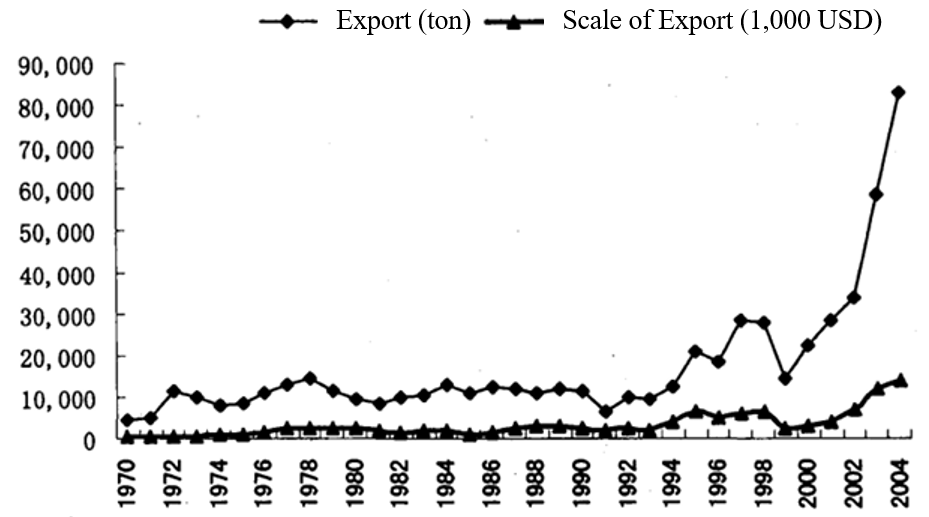

The vegetable economy was affected by the introduction of tomatoes. Since 1961, the yield of tomatoes has experienced an unprecedented rate of growth. According to Figure 3, the yield of tomatoes increased from about 5,000,000 tons to about 35,000,000 tons at the end of 2005. In addition, according to Figure 4, by 2004, the export value of tomatoes in China increased to about 10,000,000 dollars. Meanwhile, the rate of production of tomatoes in China was raised to 1.35%, ranked as the 12th worldwide in that year. These data show the economic impacts brought by tomatoes and the gradual improvement in economic participation of China in the world.

Dietary impacts

PFT’s soft peel makes it easy for humans to scramble it into juices, which is affinitive with the dietary habits in northern China. The low temperature made food with high energy necessary, so stir-fried food with oil became popular in northern China. “Tomato with scrambled eggs” and similar kinds of meals that use tomato and oil as fried food became popular in the early period of the Republic of China in northern regions [5]. The unique nutrients in tomatoes and their unique flavors make it possible for the combination of this exotic vegetable and local methods of cooking. Consequently, the range of ingredients in Chinese meals was extended, leading to impacts on regional dietary changes. Nowadays, tomatoes are promoted by businesses to encourage the public to add them to their daily diets.

RFT has a harder peel compared to PFT because of the accumulation of flavonoids. This is relevant to the subtle improvement of food in southern regions. The characteristics of the peel are relevant to the boiling method in Southern China. It is noteworthy that tomatoes are used as flavors instead of main “roles” in meals in southern regions, like the “Tea with Ganzimi,” which uses tomato as a kind of flavor with sugar to boil with tea.

In conclusion, the introduction of tomatoes made a difference in the structure and the attitude of Chinese residents toward exotic food.

Conclusion

The paper mainly discusses the introduction of tomatoes to China and the conditions that facilitated their successful adaptation. The tomato, originating from North and South America, was spread to other continents with the advancement of navigation technology. The two main routes for the introduction of tomatoes to China were the Heilongjiang and Guangdong routes.

The soil and climate conditions in different regions created distinct environments for the tomatoes to adapt to, eventually leading to the development of different subspecies. The species cultivated by residents in the north evolved as PFT, while other species, such as RFT, developed in Guangdong. RFT exhibits a red appearance due to a favorable climate for synthesizing colored substances, including flavonoids, though it contains a lower level of sugar. In contrast, PFT shows a faint red or pink appearance because of the excessively low temperature. However, the significant temperature difference between day and night in northern regions favors sugar synthesis. Additionally, the nutrient-rich soil in the northern area contributes to the synthesis of essential nutrients [13-16].

The introduction and spread of the tomato have triggered economic development and preferences of the residents towards the food. In conclusion, the introduction of tomatoes to China was mainly divided into two routes, each with its unique advantages and characteristics. The impacts of the introduction are divided into several aspects, highlighting the tomato’s potential as an economic crop and its influence on residents’ diets.

References

[1] Yao, Y., Huang, J., Yan, Y., & Chen, H. (2005). The agricultural sciences and technologies introduced by the Journal of Beizhi Agricultural Science from the West and their significance in sci-tech. JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL UNIVERSITY OF HEBEI, 28(3).

[2] Lin, T., Zhu, G., Zhang J., Xu, X., Yu Q., Zheng, Z., … & Xue, Y. (2017). Genomic analysis reveals the history of tomato breeding. Hereditas, 36(12), 1275-1276.

[3] Rick, C. M., & Holle, M. (1990). Andean Lycopersicon esculentum var. cerasiforme: genetic variation and its evolutionary significance. Economic Botany, 44(Suppl 3), 69-78.

[4] Xiao, Y., An, Z., Huang Y., Li, S., & Zhang B. (2017). Preliminary exploration of the history of tomato development and dissemination. CHINA VEGATABLES, (12), 77-80.

[5] Liu, Y. (2007). RESEARCH ON THE SPREAD OF TOMATO AND ITS INFLUENCE IN CHINA (Doctoral dissertation). Nanjing: Nanjing Agricultural University.

[6] Zhang, P. (2006). Explanation and exploration of the names of Chinese vegetables.

[7] Liu, W. (1991). Dian Annals. Yunnan Education Press.

[8] Zhang, Y., & Xiang, M. (2016). The Names of Tomatoes in Chinese Dialects. Modern Linguistics, 4, 56.

[9] Liao, F., & Ke, Y. Annals of Hulan County during the Republic of China. Local Gazetteer of Alechu Kago during the Guangxu reign.

[10] Ji, Y. (2024). Art as a catalyst: a revitalization strategy for the cultural landscape heritage of Middle Eastern railways. International Academic Forum on Cultural and Artistic Innovation, 3(9), 39-42.

[11] Li, L., Peng, X., Qian, R., Wang, J., Du, H., & Gao, L. (2024). Spatial Variation Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Black Soil Quality in Typical Water-Eroded Sloping Cropland. Journals of Soil and Water Conservation.

[12] Leyva, R., Constán-Aguilar, C., Blasco, B., Sánchez-Rodríguez, E., Romero, L., Soriano, T., & Ruíz, J. M. (2014). Effects of climatic control on tomato yield and nutritional quality in Mediterranean screenhouse. Journal of the science of food and agriculture, 94(1), 63–70.

[13] Liu, F., Zhang, G. L., Song, X., Li, D., Zhao, Y., Yang, J., … & Yang, F. (2020). High-resolution and three-dimensional mapping of soil texture of China. Geoderma, 361, 114061.

[14] Jin-Xin, W. A. N. G., Qing-jun, L. I., & Yan, Z. H. A. N. G. (2021). The influence of potassium fertilizer on the growth, yield, and the quality of different tomato species. Soil and Fertilizer Sciences in China, (3), 96-101.

[15] Zhang, C., Li, X., Yan, H., Ullah, I., Zuo, Z., Li, L., & Yu, J. (2020). Effects of irrigation quantity and biochar on soil physical properties, growth characteristics, yield, and quality of greenhouse tomato. Agricultural Water Management, 241, 106263.

[16] Tian, M. (2020). Do you know the requirements for growth of the tomato? Xinlang News. https://k.sina.cn/article_7233330430_1af23dcfe00100o61j.html

[17] Liang, J., Liu, Z., Tian, Y., Shi, H., Fei, Y., Qi, J., & Mo, L. (2023). Research on health risk assessment of heavy metals in soil based on multi-factor source apportionment: A case study in Guangdong Province, China. Science of the Total Environment, 858, 159991.

[18] Singh, D. P., Rai, N., Farag, M. A., Maurya, S., Yerasu, S. R., Bisen, M. S., … & Behera, T. K. (2024). Metabolic diversity, biosynthetic pathways, and metabolite biomarkers analyzed via untargeted metabolomics and the antioxidant potential reveal high-temperature tolerance in a tomato hybrid. Plant Stress, 11, 100420.

[19] Shi, Y., Liu, H., Ke, J., Ma, Q., & Wang, S. (2024). Research advances in cyclic nucleotide-gated channels in plants. Chinese Bulletin of Botany, 0-0.

About the author

Tengyu Cui

Tengyu is a student from the A-Level program, Grade 11, Beijing National Day School, China. He currently resides in Beijing, China, and he is 17 years old. He has a passion for exploring food science and food history. With a background of a high school student in Beijing, Tengyu has explored disciplines relevant to biology and food science. Having an interest in extracurricular research, Tengyu has done studies about postharvest fruit preservation and composed a review essay about the pros and cons of food preservation in solving a global challenge.

Having entered an international competition called iGEM, Tengyu has collaborated with students from other high schools in China to manage to make an aromatherapy product from tea residue by using E. coli, as an expression carrier to catalyze the β-carotene in tea residue to β-ionone. Frequently sanguine to explore and review knowledge, Tengyu continues to do research on the relationships among people, the environment, and the food.