Author: Cheng-Chieh Chiang

Mentor: Dr. Eric Golson, University of Surrey

Kang Chiao International School

October 1, 2021

Abstract

Over the past 20 years, China could be seen rising steadily to one of the world’s great powers. Politically, China has an active foreign policy, and actively engages in protecting territorial sovereignty and gaining international influence. Economically, by joining the WTO, China has since transformed into a world economy. Externally, these changes also result in a variety of economic and political counterattacks by the US. Internally, the Chinese Communist Party’s determination to consolidate its power has led the nation into increasingly centralized both economically and politically. This paper is going to argue that attempting to reconcile economic liberalization with authorization is not sustainable.

Challenges Faced by China amid Economic Liberalization

China’s economic rise in the past 20 years saw the nation emerge as a world superpower thanks to free-market reforms undertaken in the 1990s. Externally, it has been active in asserting control over a large share of territory in the Pacific and more generally, in exercising international influence; internally, it is focused on solidifying the CCP regime by more tightly controlling the country and its citizens. However, these changes are increasingly at odds with

economic liberalization; the benefits that come with opening the market cannot coexist with tighter control by the party. As a result, because it is not possible to reconcile authoritarianism with free markets and private property, the Chinese government’s current policy is not sustainable.

Literature Review

China’s economic rise to one of the world’s great powers is undeniable. But opinions differ on whether China will compete with the International order created by the US hegemony 3 and whether it has the ability to become the next hegemony. Some findings suggest that there are critical barriers China must cross in order to create a hegemony like the US.

In “China’s rise and US hegemony,” Rosemary Foot argues that despite China’s material resurgence, it is not able to become a true hegemon due to its inability to find a balance between protecting its own interests and reassuring its neighbors that it does not threaten their interests (Foot, 2019). China’s material resurgence in recent years is evidenced by increased exports, investments, and trade, a growing scientific, particularly space ambition, and having the world’s second-largest defense budget. China’s management strategy in East Asia, despite attempts to reassure its neighbors through creating international organizations, is characterized by its determination to protect its sovereign claims and engage in bilateral relationships such as in the BRI. As Foot argues, China would be at most a restricted constituency due to the leveraging of its economic and military power against seeking bilateral relationships which create normative order and stabilize the region.

Some findings suggest that China is beginning to compete with the US, and possibly create a new international order.

Mearsheimer uses the concept of offensive realism to argue US engagement policy with China is doomed to fail, and this paper takes this as the point of departure to argue that China’s expanding power to protect its interest is inevitable (Mearsheimer, 2001). In international anarchy, a world absent of a central and dominant authority, since states can never be sure of others’ intention, in order to maximize security, a state would always compete with each other. Mearsheimer uses this to predict that in order to achieve maximum security, China would want to create a regional hegemon, hence it would not settle with US possible containment policies.

Findings from Cooley and Nexon further discuss China’s threat to US hegemony and suggest that China is beginning to compete with US hegemony and possibly create a new international order (). According to their paper, since 1997, China and Russia made it clear their goal was to promote a multi-polar world; they allied in the UN, tolerated each others’ international projects, and both created international institutions to gather more allies. China also routinely provides economic aid to other countries, with the goal of gaining allies in these international institutions. These countries, which before were either directly or indirectly a part of the US hegemonic project, now have a choice to join China. The post-Cold War liberal international order was also challenged by illiberal competitors in many areas. Far-right organizations in traditional western liberal countries have gained increasing international recognition and support from Beijing and Moscow; many countries such as China began to sponsor their own NGOs to compete with western ones; authoritarian countries began to believe liberal ideals are a threat to their security. These movements can be understood as evidence of China’s increasing power in the world.

Malkin takes on a different approach and argues that China has the potential to challenge the US structural power from the aspect of productive power (Malkin 2020). He argues that the recent Chinese policy MIC 2025 had allowed it to ascend in the global value chain. China is able to increase its influence by capturing more global intangible assets and raising its market share using favorable IP commercialization, standardization, and competition policies. This paper is going to evaluate China’s aggressive economic approaches like this.

China’s foreign strategy

Over the past 20 years, China’s foreign policy can be described as highly active. This paper will categorize its policy as both protection of territorial sovereignty and attempting to gain international influence.

Protecting territorial sovereignty has long been one of China’s biggest foreign policy goals. One of the most important strategic competitions China is involved in is over the South China Sea (SCS). With an estimated 11 billion barrels of untapped oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, SCS, countries around the region such as China, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam have been vying for control over the region (Territorial disputes in the South China Sea). Recently, China has been seen through satellite images working to increase the size or even build new islands in an attempt to gain more control. China’s strategy in SCS can be seen as an attempt to gradually shift the status quo in its favor without engaging in actual military conflicts. Some refer to this as a salami-slicing strategy where China slowly captures and sets up defenses around new territories to gradually wear its opponents down.

Another strategy China uses to create influence is by engaging with international alliances and organizations while also building regional institutions. For example, China’s power and influence in the UN are increasing significantly as it provides economic support to other countries. In a United Nations Human Rights Council in 2020, a total of 53 countries supported China’s new national security law, overwhelming the 27 members that were against it (Landslide support for Hk law at UNHRC). China has also been actively creating and joining regional economic institutions and signing trade agreements as a means to better connect with other countries in the regions such as Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Alongside this is the promotion of the Belt Road Initiative (BRI). BRI manifests China’s attempt to use its economic leverage to gain allies and influence their policies to oppose the US existing order. However, there are a few problems with this kind of foreign policy. First, using economic leverage to build relationships is not secure. It is likely that once China becomes unable to provide economic support, its allies will quickly turn away. Second, China’s showing off its military power, as in the case of SCS, undermines its credibility that it would be able to maintain safety and order in the region. Third, China’s activity is predatory: many countries China works with have low credit rankings. This slows BRI investment deals and raises concerns inside China regarding the implementation of BRI

US policy on China

American activity has largely been to engage with China economically, believing this would push China towards free-market principles. In 2001, the House of Representatives approved the US-China Relations Act of 2000, which essentially showed their support for China to join the WTO. Consisting of 164 members as of 2021, WTO encourages freer trade, fewer economic barriers, and better trade deals among its members. Then-president Bill Clinton hoped that by joining the WTO, China could accelerate the progress of opening up its economy to the rest of the world, and naturally move away from the communist political model and join the US-led liberal democratic order. Specifically, China would have to reduce tariffs, guarantee intellectual property rights. Politically, WTO and its members can serve as a check for the Chinese communist government. In reality, while China’s economy grew remarkably, its political transformation did not go as the US hoped it would. From 1990 to 2012, the number of people in China living in extreme poverty had fallen two-thirds of the population to under 0.5% ); China’s economy now is 11 times larger than it was in 2001 (China Poverty and Equity Brief). However, the CCP was able to use economic growth to legitimize its rule in China. During the past 20 years, it maintained tight control in Chinese private and public businesses, with an estimated 70% of about 1.86 million private companies having internal CCP-ties.

Clinton also hoped Americans would profit economically from China joining the WTO. In reality, while American consumers benefited from cheaper Chinese products and corporations took advantage of China’s large market, much American labor in the manufacturing industries lost jobs due to China’s competition. President Trump, during his 2016 presidential campaign, used this as rhetoric, saying “They’re using our country as a piggy bank to rebuild China,” Trump said. “We have to stop our jobs from being stolen from us.” A report by the Economic Policy Institute estimates the growing trade deficit with China has cost 3.7 million American jobs since China joined WTO in 2001. It is notable the report also found job losses from the trade deficit in the electronic and computer parts industry accounted for 36.2% of all job losses (Scott & Mokhiber, 2020). The US used to have a comparative advantage in advanced technology, but the fact that China now dominates manufacturing in this industry shows that the former took full advantage in using the opportunity to join the WTO to transform its industrial focus.

While the US economic policy on China at the start of the century was mainly concerned with helping it open up its market to the world, its policy has since changed rapidly in the last 5 years. The US began to pass tariffs and impose sanctions aimed to discourage China’s acquisition of America’s technological expertise. To the US, China’s use of industrial policies, subsidies, and regulatory authorities to acquire technological skills is aggressive. The Made in China 2025 policy, for example, was aimed to improve China’s competitiveness in technological industries by gaining expertise from the US firms. The US suspects IP theft and cyber espionage may be ways that China uses to achieve its goals.

In a 2018 report, the US trade representative found China engaged in (1) forced technology transfer, (2) cyber-enabled theft of U.S. IP and trade secrets, (3) discriminatory and non-market licensing practices, and (4) state-funded strategic acquisition of U.S. assets. Subsequently, the US Congress passed a tariff on Chinese imports worth approximately 250 billion dollars, while China countered with a tariff of about 110 billion. The US imports from China had fallen from 538 billion to 434 billion dollars from 2018 to 2020, just under 100 billion dollars in 2 years (United States Census Bureau).

Imposing tariffs, though significant, was not the only action taken by the US on China, however. The Trump Administration tightened technology exports to China’s Huawei and restricted the use of universal funds to buy the company’s equipment. The Administration also posed sanctions on certain entities and officials in Xinjiang due to the findings on crime against humanity and genocides. Reacting to the National Security Law in Hong Kong, the US passed a series of sanctions and began to eliminate Hong Kong’s special economic status in American trade law. Although the two countries signed a phase one agreement in January of 2020, easing the tensions from the trade war, the economic competition between the two countries is very much alive and has not de-escalated.

Cybersecurity is one of the aspects that intensified China-US relations. The US accused China of endorsing or supporting espionage attacks about a decade ago. On May 19, 2014, for example, the US indicted 5 Chinese military hackers suspected of cyber espionage against 6 US nationals in nuclear power, metals, and solar products industries (The US Department of Justice).

Since this was a hack carried out by members of the Chinese military, it represents the first charge by the US against a state actor in hacking. In July of 2021, the Biden administration accused China of cyberattacks, and according to their findings, China’s hacking has transformed into a far more sophisticated satellite network that perpetuates American companies and interests. The US position on Taiwan (ROC) also causes issues with China. Taiwan’s strait issue has long been the main focus of China’s foreign relations, and China strongly asserts sovereignty over Taiwan.

The US position on Taiwan can be seen as a strong indicator of the relationship between the two countries. While the US had ceased recognizing ROC since 1979, due to the Taiwan Relations Act in 1979, the US continues to provide military support to maintain Taiwan’s self-defense capability. The US policy on Taiwan had been purposely kept ambiguous, in order to stabilize cross-strait relations. However, during President Trump’s administration, US-Taiwan ties became significantly stronger following a series of new laws passed by the US. Following the Taiwan Travel Act in March of 2018, high-level diplomatic officials from two countries were encouraged to visit each other. In March of 2020, Trump passed the TAIPEI Act, which further increased the scope of their relationship. Additionally, the Trump Administration escalated arms sales, totaling 18,277.8 million dollars worth of arms to Taiwan in 4 years. In comparison, in 8 years as president, Obama sold only 14,070 million dollars worth of arms.

China has increasingly pressed the Taiwan issue. It has not held back from taking action. In fact, in 2020, a year where most countries were affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, China made a record 380 incursions into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone (China’s record entry of Taiwan Airspace, 2021). This may be in part because Taiwan’s ADIZ actually stretches into China’s mainland border as shown in Figure 1, so the incursions may not necessarily threaten Taiwan. However, these actions could be seen merely as a political choice by China directed at the US and its allies for their continuous support for Taiwan; most countries believe that a settlement should be reached on this issue.

Internal Issues

Doing business in China is not necessarily straightforward. It ranks well in the World Bank’s ease of doing business index. But there are some areas of weakness. For example, China is ranked 105 in the world for tax collection. Transactions were not adequately protected by laws and that the government reserves the right to make changes in favor of domestic firms. The ranking is measured by the number of payments, time, and the total tax rate of a case study firm, usually a foreign one. This shows that China imposes a lot of restrictions on foreign firms in order to protect the domestic ones, showing that China is very internally centralized, with a top-to-bottom system. China is ranked 80 in ease of getting credit, which, according to the World Bank “measures the legal rights of borrowers and lenders in secured transactions (or collateral) laws and bankruptcy laws to assess how well these laws facilitate lending.”

This spills over into other areas of business.

Most recently, through passing a series of laws aimed at limiting the expansion of big tech companies, the Chinese government shows its determination to prevent the tech titans from gaining too much political power and limit external, western influence. In April 2021, China imposed a series of restructuring on Jack Ma’s Ant Group, which not only undermined its values but also split the powerful tech firm into several independent businesses. With over 730 million monthly users per month, Ant’s Alipay has a huge amount of consumer data that not only gives it a big advantage in competition but also prompted the government to take action. Other major tech companies such as Tencent and Didi, also faced a crackdown. Since being fined for monopolistic behavior, their stock values had fallen 7% and 27% respectively (Grothau, 2021).

In 2018, the National People’s Congress passed a constitutional change that removes the presidential term limit and allows President Xi Jinping to serve as president for life. This change effectively centralized political power in China into the hands of a single man. Just 10 years ago, within the CCP, there were various factions and then-president Hu had to listen to different opinions. Now, Xi was able to elevate his status and ideology, which possibly meant a more centralized and authoritarian communist government that reduces market power.

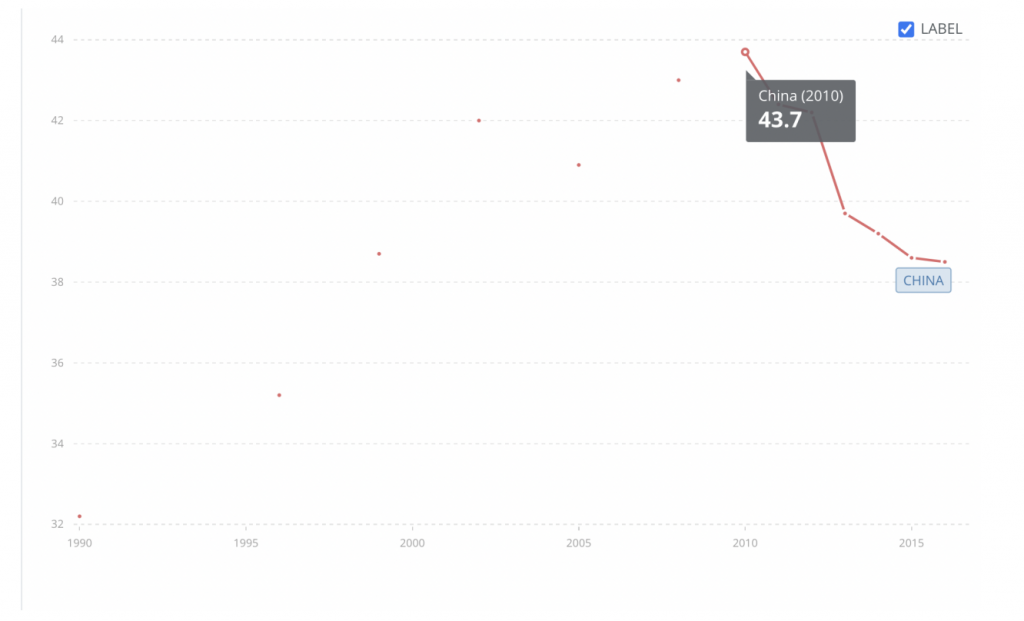

According to the analysis by the World Bank, China’s rising inequality from 1990 to 2010 can be attributed to the rapid growth of income from the richer group, growing rural-urban difference, and income from private property, which in turn was a result of China’s opening up its market during the 1990s (Sicular, 2013). Xi’s policy of focusing on internal centralization of power over market growth had led to an improvement in China’s income inequality. According to the World Bank, China’s Gini coefficient data rose steadily from 1990 and peaked at 43.7 in 2010, as shown in Figure 2. Then declined sharply until 2016, the last year for which the World Bank has data.

The fact that the income of the richer group is growing faster than the poorer group is a reflection of a capitalistic market that China was gradually transforming into. While people who live in cities have access to a more modern and capitalistic market and experience rapid income growth, the income of rural households, though growing, is not increasing nearly as fast (China Poverty and Equity Brief from World Bank).

The trend changed in the 2010s. Besides the increasing number of SOEs and tech companies crackdown by the Chinese government, it also implemented a series of pro-farmer policies, personal income tax reform, and financial inclusions, which were aimed to reduce the rural-urban gap. With the “Grain for Green” program aimed to mitigate flooding and soil erosion, the Chinese government sent 124 million people from rural areas, mostly farmers, to transform farmland susceptible to soil erosion into forests. The program not only successfully grew its forest area from 16.74% to 22.5%, an amazing achievement, but it also helped improve the economic situation for millions of rural Chinese people, showing the government’s determination and ability to greatly influence the nation’s economy (How China brought its forests back to life in a decade).

The growth of SOE involvement in Chinese Economic life, instead of reform and reduction of state-owned enterprises (SOE) in China, is also an indicator of Xi’s relentless effort to increase the state’s involvement in the economy. In the 1990s, China went through a series of market reforms under Deng Xiaoping. As a result, state-owned enterprises began to adopt western governance structures and aimed to improve efficiency and productivity. In the 2000s, with the creation of new government bodies such as the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC), the central government began to exert more control over the SOEs.

The Xi Jinping era saw an even larger role played by the SOEs. Since 2003, central SOEs in China have grown from 96 to 189, according to the SASAC website. And, according to the World Bank, although it only accounted for around 25% of the economy, these SOEs were involved in key industries such as energy, aviation, finance, telecoms, and transportation (Zhang). CCP also uses these SOEs to implement its policies, such as the development of semiconductor industries and participation in projects related to the Belt Road Initiative. These actions undermine free-market principles.

Megamerger and global implication

The monopolistic position of these SOEs also gives them an advantage in competition against foreign firms. The government will bail out the troubling SOEs by either giving them lower interest rates or helping merge the companies in megamerger deals. Through these megamergers, China would be able to create large competitive firms that can compete on the global stage. This would undermine global competitiveness in certain sectors as these Chinese firms can offer products at much lower prices with support from the Chinese government.

Media Control

Another way that the CCP uses to gain internal control is through repression of ideas that threaten the legitimacy of the party. There are two forms of repression: media censorship and suppression of minority groups. The Chinese government had long kept control over traditional and new media by using firewalls, jailing up journalists, or targeting publications or websites. Chinese internet censorship is especially notorious for its strict censoring system, known as the Great Firewall. Western websites such as YouTube, Facebook, and some Google services are banned. For two consecutive years, Freedom House ranked China last out of 65 countries in media freedom.

This kind of repression by the Chinese government was not done without a reaction from the public. In more subtle ways, bloggers in sites like Weibo develop an extensive series of pubs, slangs, and memes to avoid censors and voice their own opinions. Some Chinese Internet users also use software programs such as Ultrasurf, Psiphon, and Freegate to get around the firewall. In fact, according to the US Congress, around 1 to 8 percent of Chinese Internet users use proxy servers or VPNs to get around the government’s censor (China, Internet Freedom, and U.S. Policy). Public dissent of government restrictions is rare, but not completely unseen in China. Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo was a prominent activist who opposed the CCP’s oppressive regime and censorship in China. In short, despite CCP’s wide-reaching measures to impose restrictions on Chinese people, their actions are not completely accepted and there are voices of dissent in China.

China also suppresses minority groups that are culturally different from the Han ethnic group. A prominent example is the Uyghurs in Xinjiang. They are a mostly-Muslim ethnic group in the northwestern region of Xinjiang, and China has been accused of committing a crime against humanity and genocides. The Chinese build re-education camps that use Uyghurs as forced labor. They also create an extensive network of surveillance, including police, cameras, and checkpoints that scan and record individual faces. They actively target religious figures in the regions, in an attempt to eradicate Uyghurs culture.

Conclusion

On weighing up the evidence, we find that CCP is trying to walk a very tight line between authoritarianism and free-market principles, a difficult policy to achieve. Centering around territorial sovereignty protection and gaining international influences, China’s foreign policies are very active. Its activities in the SCS, involvement in international institutions such as the UN, and promotion of the BRI show its commitment to become a global power.

The USA’s relationship with China has intensified in the past 30 years as China swiftly grew to great power. Economically, China’s joining of the WTO has benefitted China significantly, as the former was able to maintain its authoritarian political structure while reaping the benefits from opening its international market. Therefore, the US has taken a variety of economic counterattacks, ranging from tariffs to sanctions on Chinese officials. The two countries also engaged heavily on other issues such as cybersecurity and cross-strait relations. Although a direct conflict is unlikely to happen between the two nations, they were actively opposing each other in a variety of ways.

Internally, under President Xi’s leadership, China is gradually heading towards a more authoritarian government, which will very likely be at the expense of its economic growth. China’s crackdown on tech companies, removal of Xi’s term limit, and policy addressing income inequality, and the number of SOEs can all be seen as evidence of Xi’s relentless effort to centralize the government’s control. As China’s internal repression begins to extend, the legitimacy of the ruling party will very likely be called into question.

References

(央 企)名录 -国务院国有资产监督管理委员会. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2021, from http://www.sasac.gov.cn/n2588035/n2641579/n2641645/index.html.

Borst, N. (2021, May 17). Has China given up on state-owned enterprise reform? Lowy Institute. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/has-china-given-state-owned-enterprise-reform.

China Poverty and equity briefs. World Bank. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/poverty/987B9C90-CB9F-4D93-AE8C-7 50588BF00QA/AM2021/Global_POVEQ_CHN.pdf

China, internet freedom, and U.S. policy. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R42601.pdf.

China’s record entry of Taiwan Airspace about sending signals to the world. South China Morning Post. (2021, January 6). Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3116557/pla-warplanes-made-record380-incursions-taiwans-airspace-2020.

Cooley, A., & Nexon, D. H. (2020). How hegemony ends. Foreign Affairs, 99(4), 143-157. Council on Foreign Relations. (n.d.). Territorial disputes in the South China Sea | global conflict tracker. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/territorial-disputes-south-china-sea.

Council on Foreign Relations. (n.d.). What happened when China joined the WTO? Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://world101.cfr.org/global-era-issues/trade/what-happened-when-china-joined-wto.

Diplomat, B. H. for T. (2020, July 23). China’s pressure costs Vietnam $1 billion in the South China Sea. – The Diplomat. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://thediplomat.com/2020/07/chinas-pressure-costs-vietnam-1-billion-in-the-south-china-sea/.

Foot, R. (2019). China’s rise and US hegemony: Renegotiating hegemonic order in East Asia? International Politics, 57(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-019-00189-5

Grothaus, M. (2021, July 8). Didi, Alibaba, and Tencent shares plummet after China cracks down on its own tech giants. Fast Company. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.fastcompany.com/90653737/didi-alibaba-and-tencent-shares-plummet-afterchina-cracks-down-on-its-own-tech-giants.

How China brought its forests back to life in a decade. Rapid Transition Alliance. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.rapidtransition.org/stories/how-china-brought-its-forests-back-to-life-in-a-decade/.

Luce, D. D. (2021, April 11). China tries to wear down its neighbors with pressure tactics. NBCNews.com. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/china-tries-wear-down-its-neighbors-pressure-tactics-n1263631.

Malkin, A. (2020). The made in China Challenge to US structural power: Industrial policy, intellectual property and multinational corporations. Review of International Political Economy, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1824930

Mearsheimer, J. J. (2001). The tragedy of great power politics. W. W. Norton & Company.

O’Connor, S. (2018, May 24). SOE Megamergers Signal New Direction in China’s Economic Policy. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/SOE%20Megamergers.pdf.

Perlroth, N. (2021, July 20). How China transformed into a prime cyber threat to the U.S. The New York Times. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from http://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/19/technology/china-hacking-us.html.

Person. (2021, April 12). China extends crackdown on Jack Ma’s empire with enforced revamp of Ant Group. Reuters. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.reuters.com/business/chinas-ant-group-become-financial-holding-company-central-bank-2021-04-12/.

Pike, J. (n.d.). Taiwan – Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ). Global Security. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/taiwan/adiz.htm.

Report • By Robert E. Scott and Zane Mokhiber • January 30. (n.d.). Growing China trade deficit cost 3.7 million American jobs between 2001 and 2018: Jobs Lost in every U.S. state and Congressional District. Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from

https://www.epi.org/publication/growing-china-trade-deficits-costs-us-jobs/.

Sicular, T. (2013). The Challenge of High Inequality in China. Inequality in Focus, 2(2), 1–4. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/Poverty%20documents/Inequality-In-Focus-0813.pdf.

Silencing the messenger: Communication apps under pressure. Freedom House. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-net/2016/silencing-messenger-communication-a pps-under-pressure.

Taiwan Relations Act (Public Law 96-8, 22 U.S.C. 3301 et seq..). American Institute in Taiwan. (2020, December 30). Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.ait.org.tw/our-relationship/policy-history/key-u-s-foreign-policy-documentsregion/taiwan-relations-act/.

Times, G. (n.d.). Landslide support for HK Law at UNHRC. Global Times. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1193226.shtml.

Trump says us jobs get ‘stolen’ by China. well, here are the countries ‘stealing’ Chinese jobs. Trump says US jobs get ‘stolen’ by China. Well, here are the countries ‘stealing’ jobs from China. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2021, from

https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-09-27/trump-says-us-jobs-get-stolen-china-well-here-are-countries-stealing-chinese-jobs.

U.S. charges five Chinese military hackers for cyber espionage against U.S. corporations and a Labor Organization for commercial advantage. The United States Department of Justice. (2015, July 22). Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/us-charges-five-chinese-military-hackers-cyber-espionage-against-us-corporations-and-labor.

United States Census Bureau. (n.d.). U.S. Trade with China. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5700.html.

United States Government 2018, Findings of the Investigation Into China’s Acts, Policies, and Practices Related to Technology Transfer, Intellectual Property, And Innovation Under Section 301 Of The Trade Act Of 1974, Office Of

The United States Trade Representative. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/Section%20301%20FINAL.PDF.

Who are the Uyghurs and why is China being accused of genocide? BBC News. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-22278037.

Why it matters in getting credit – doing business – World Bank Group. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2021, from

https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/data/exploretopics/getting-credit/why-matters.

Zhang, C. (n.d.). How Much Do State-Owned Enterprises Contribute to China’s GDP and Employment? World Bank, 1–10. Retrieved October 18, 2021, from https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/449701565248091726/pdf/How-Much-DoState-Owned-Enterprises-Contribute-to-China-s-GDP-and-Employment.pdf.

About the author

Cheng-Chieh Chiang

Cheng-Chieh is interested in political science, economics, and sociology and loves golfing