Author: Carter Chen

Jiangsu province Tianyi High School

August, 2020

Introduction

Chinese economic reforms, which have been underway for three decades, have more than doubled China’s economic growth, from an average of 4.4 percent annually before 1978 to an average of 9.5 percent after 1978. It has resulted in spectacular growth and poverty reduction, transforming China from the world’s poorest country into a major economic power. Nowadays, China is the largest producer and consumer of industrial staples and a hub of international trade. Statistically, the current size of the Chinese economy, in terms of GDP, is larger than the sum of eighty-three countries in Eastern Europe, the CIS, and all of Africa.

With a booming economy, nevertheless, China’s potential has not fully developed. Looking at its current situation, there are obvious deficiencies which are hindering its development in the areas of schooling, high-tech innovations and inequality. Each of these need to be tackled for China to move to the next level of economic growth.

China is suffering from a gaping chasm in the school system. Superficially, the standard test system performs well as an equalizer in China’s education. Indeed, it merely contributes to a fairly equal access to education in urban areas, namely developed cities such as Shanghai and Beijing. As a counterpart to urban cities, rural areas are still afflicted by uneven distribution of education. Living in remote villages, villagers share an average education attainment of primary school due to the lack of financial growth and limited education awareness. Obtaining a low education level, many talents in rural areas are stifled and hindered from shining their potentials.

Moreover, China is facing a scarcity regarding to its high-tech innovations. Though putting a huge stock in developing technology, compared with other developed countries, China is still fallen behind. To name an example, China has struggled to develop “self-sufficiency” in cutting-edge semiconductors. Originally outsourced to foreign investments and innovations, China is in great demand of new technology inventions. Consequently, a lack of domestic innovations have negatively impacted China’s productivity.

As the result of more than two decades of rapid economic growth in China, millions have been lifted out of poverty, resulting in an impressive decline in the poverty headcount ratio. However, economic growth has not benefited all segments of the population equally or at the same pace, causing some income disparities to grow, resulting in a large increase in income inequality. This widening inequality has weakened the support for growth-enhancing economic reforms and may spur Chinese governments to adopt populist policies and weaken reform prospects.

The majority of previous studies focused on China’s spectacular performance in the area of poverty alleviation and economic reforms. To expand public opinions and reveal potential dangers, this study will analyze the current Chinese deficiencies behind its thriving economy. The null hypothesis is that despite its current achievements, China’s development is impeded by its education disparity, income inequality, and limited high-tech innovations.

Literature Review

The existing literature on this topic has generally been complementary of China’s rise, but pointing to the normal weaknesses of a developing state. In The Fundamental Institutions of China’s Reforms and Development by Chenggang Xu, China’s economic reforms has performed a spectacular job during the last twenty years, reducing poverty at an unprecedented scale. However, from the viewpoint of standard wisdom, China’s institutions and policy are notoriously weak. Conventionally, countries should protect private property rights and refrain itself completely from interfering business. Nevertheless, China’s government is deeply involved in domestic business, which would incur serious corruption and is believed to be ill-suited for development. The regionally decentralized authoritarian (RDA) system ensures China’s market can function well. The RDA system is characterized by highly centralized political and personnel controls, and, a diametrically opposed, decentralized regional administration and economic system This could be reformed so subnational governments can control their own business and offering them incentives, government could promote the economics growth, alluring each local government to compete in quantifiable targets.

According to Brandt, Ma and Rawski’s From Divergence to Convergence: Reevaluating the History Behind China’s Economic Boom China’s modern economic growth was incurred firstly by the outbreak of WWI, which weakened competitive pressure from European imports, spurred the expansion of domestic manufacturing in the absence of tariff autonomy. Attracting vast amount of foreign investment, China’s domestic investment was increased, leading to an economic expansion. Another factor is the improvement of transportation is that in China completion of railways between cities hugely reduced time needed to ship goods, thus expediting manufacture. There was also a sweeping transformation in banking and finance: hard currency such as silvers were substituted by banknotes, contributing greatly to the convenience of trading. These authors also argue China’s economy growth was also rested on many important political changes through 2013. The revival of household farming, named Household Responsibility System, elicited an explosive growth in food output. Along with the agriculture shifts, China also embraced a decentralizing fiscal policy. Instead of the central government implementing every single order, subnational institutions were endowed with rights to directly appoint tax and revenues.

Education in rural areas remains a problem. In Yongqing Dong’s paper Intergenerational transmission of education: The case of rural China, it is argued that in rural areas there is less formalized education, with an intergenerational transmission of education. According to the data, proper education could bring enormous benefits to rural individuals: providing access to off-farm employment opportunities, improving health status and productivity. As the outcome suggests, the government has the necessity to enhance rural people’s education attainment, since raising education bar of one generation historically leads to significant educations gains for the next. Moreover, government should consider programs which release rural students from intense financial restrictions so these individuals can gain college or high school level education. generation. The popularizing of education would have long-term effect for accumulation of educational attainment in these areas and lead to more scientific gains and domestic ingenuity. As a result, by taking advantage of the natural effect of the intergenerational transmission of education government may ensure long-term fortitude among its rural people

Analysis

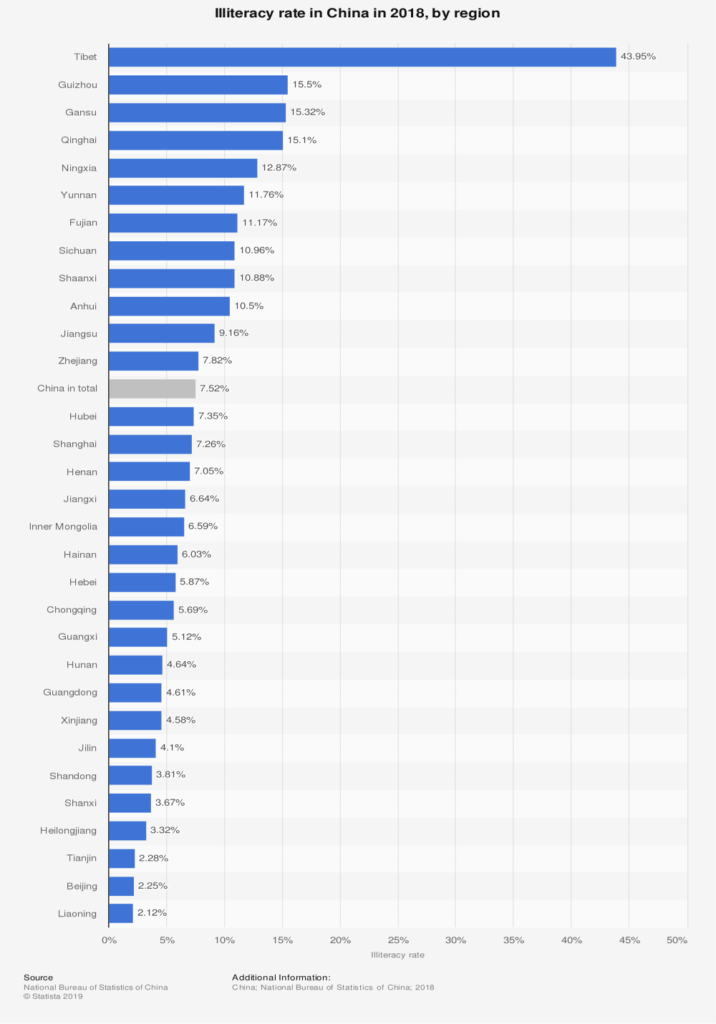

Turning to data for the arguments for this paper, normally, Illiterate population refers to the proportion of the population aged 15 and older who are unable to read or have difficulty in reading. In China through the education reform, the number of illiterate people is hugely decreased; moreover, since 2015, mandatory free primary school education has helped to virtually eradicated illiteracy. People have recognized literacy as an indispensable quality that it poses the basis for all other forms of education. Additionally, literacy skills are essential for the promotion of sustainable development, both in terms of economic progress and social advance. Though China has took a large leap forward in eliminating illiterate population, regional disparities in illiteracy rate still persist in China. Illiteracy in developed regions, with prosperous economy and advanced education, tends to be lower than in rural and undeveloped areas.

In figure 1, the illiteracy rate in Tibet has been at a staggering 43.95%, meaning roughly half of its population are unable to read and write, and thus are not able to receive any education. In comparison with China’s average rate of 7.52%, it is approximately 36 percent higher, attesting to an extraordinary inequality in education attainment across regions. Contrasting Tibet against Liaoning, a prosperous city in northern China, which has only 2.12 percent illiteracy there is a range of 42%, signifying current severe discrepancy in the regional illiteracy rate. While citizens in developed cities enjoy their fulfilled life with illiteracy rate practically eliminated, people in poor and remote regions are still afflicted by high illiteracy rate, let alone more diversely advanced education or technology improvement.

Intriguingly, as a financial center, transportation hub, and technology leader of China, Shanghai has a rather mediocre illiteracy rate of 7.26%, which is largely deviated from public expectation. According to the graph, this number is only 0.3 percent lower than the average, much higher than it supposed to be for a city whose economy ranks the highest in China. This suggests there are significant differences in educational inequality. Possessing 2,195 universities and 30 million graduates, Shanghai’s education level is unquestioned. Nevertheless, its booming economy has triggered an almost outrageous tuition for even primary school. Consequently, the price for attending school poses a huge hurdle for reducing illiteracy rate. The inequal distribution of wealth hinder many children to receive necessary education. That, in turn, is hindering Shanghai from further improving its citizens’ education attainment.

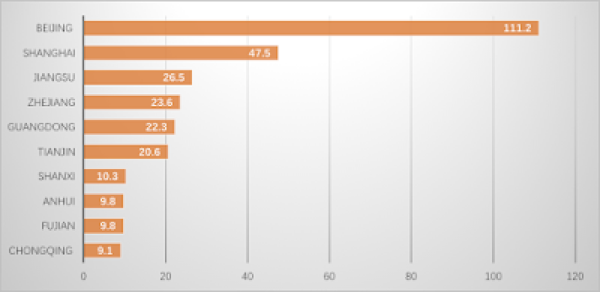

China is still recognized by some critics as a country that cannot innovate. There are various reasons for that: Chinese students are taught rote learning and do not know how to think for themselves. China is too far behind the leaders to ever catch up. Weak IP laws and enforcement mean China has been a copier of technology. In 2017, China’s investment in R&D was $370.6 billion in 2017, second to the $476.5 billion of the USA. These funds are crucial to augmenting technology transfer and expediting the acquisition of technological capability. With the unprecedented financial support, Chinese technology has achieved outstanding break through. However, it is undeniable China is still in a phase where it cannot innovate new technology independently.

The graph presented in figure 2 explains the reason for the lag in high-tech innovation. In the figure about number of patents applied by every 10,000 people, Beijing with its prosperous economy has 111.2 patents every 10,000 residents. The number decreased drastically, and for ChongQing only 9.1 patents were applied for every 100,000 people. Such disparity in patent applications indicates a staggering inequality in the resources and economy between regions. Children in under-developed regions cannot gain high-level education and do not have technology related experiences. Consequently, Chinese youngsters’ intelligence are not fully tapped. Technology innovation, which requires a tremendous talent has definitely fallen behind in China.

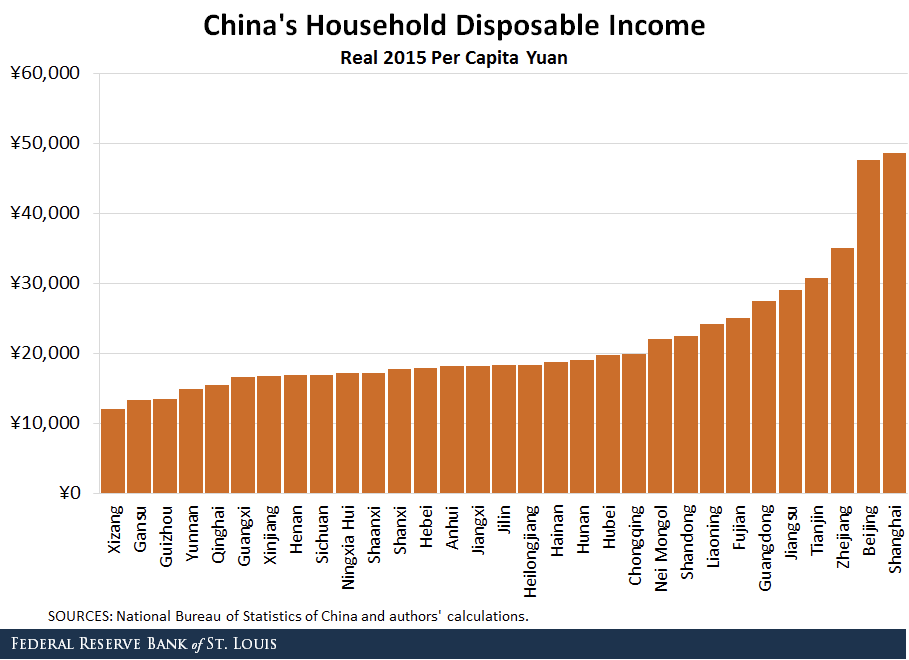

China has experienced rapid economic growth over the past two decades and is on the brink of eradicating poverty. However, income inequality increased sharply from the early 1980s and has rendered China among the most unequal countries in the world. Instead of dealing with this problem this inequality is likely to expand further in the future, leading to an increasingly severe gap in developed and undeveloped cities.

In figure 3 it is seen that households in Shanghai earn the highest average income of 50,000RMB, while Xizang has the lowest income of merely 10,000RMB. Simple calculation presents a 40,000RMB discrepancy, which is four times the average income for Xizang residents. As this gap embeds into China’s economy, all forms of development are impeded: individuals are hindered from showing their talents, due to the lack of job opportunities and education attainment in relatively poorer areas. With a limited income of 10,000RMB, it is impossible for Xizang to achieve economic growth and technology innovations. Family are forced to give up children’s education attainment, in exchange for labor force and revenue.

Additionally, the whole graph is clearly skewed to the left, as cities get further remote and inland, their average income decreases along the way. The pattern indicates the current development difference between coastal cities and inland cities in China. Cities with access to the Pacific Ocean inherently possess an advantage: Shanghai, Jiangsu, Tianjin provinces are all classic examples of developed coastal cities with access to trade, respectively earning income of 50,000RMB, 30,000RMB, and 31,000RMB. In contrast, most inland cities such as Xizang (10,000RMB) and Gansu (11,000RMB), due to their distance from ocean, maintain low average incomes. This uneven distribution of income caused by geographic traits further attest to the inequality of regional disposable income. With this unequal distribution, China’s development is hindered due to those poor cities are lagging, rendering developed cities’ boost in economy futile.

Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

Based on the analysis above, we can determine China’s economic development is impeded by its lagging quality of innovation, education disparity, and income inequality.

Education Disparity

The analysis has proven the negative implications of the chasm in regional education attainment. Children in poorly developed regions, especially those in inland rural areas, are excluded from mandatory free primary school education. This leads to a staggering discrepancy in terms of literacy rate. Armed with these facts, the Chinese government should allocate more subsidies to local governments, in the prospect of pervading rural areas with free primary school policy. By popularizing the basic education, China could tap into its talents’ potential, helping to hurdle development obstacles.

Income Inequality Tax

China’s overall economy is growing fast, but it is not growing evenly. Abysmal inequality in average disposable income is impeding China from developing further. Some Regions with only one third average income than others would produce inefficiently and developed in a low speed. As the gap augments annually, China’s economy would become unstable, facing serious internal economic inequalities. Tax and internal transfer systems play a key role in lowering overall income inequality. Through taxing residents with higher salary, China could effectively redistribute income from wealthy to those with lower incomes. While corruption is severe in China and could impede the collection of taxes, China could deploy stricter regulations regarding to corruption to eradicate its hazard.

High-Tech Innovation

China’s high-tech innovation is still behind compared to other developed countries, with fewer patents registered per capita. This largely caused by the disparity in education where talented individuals in rural areas cannot access advanced education and thus cannot contribute to technology improvement. Moreover, lower incomes also thwart their enthusiasm for innovation. To solve this impediment, China should allow individuals in rural areas high levels of education and allow them to tap into rural people’s talents. Additionally, China could enforce more policy to protect intellectual property, thus rewarding innovation and the development of new technologies.

References

Mentor: Dr. Eric Golson, University Of Surrey

Education in China – Statistics & Facts Published by C. Textor, Apr 7, 2020 https://www.statista.com/topics/2090/education-in-china/

Income and Living Standards across China- Monday January 8, 2018 By Yi Wen, Assistant Vice President and Economist, and Brian Reinbold, Research Associate

https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2018/january/income-living-standards-china

China IP Office released major IP statistics of 2018- Tian Lu Monday, January 28, 2019

http://ipkitten.blogspot.com/2019/01/china-ip-office-released-major-ip.html

About the author