Author: Emily Kim

Mentor: Dr. AbdelAziz Jalil

Bergen County Academies

Abstract

Every person has two kidney organs responsible for filtering and cleaning fluid waste from the blood. Kidney disease occurs when one or both kidneys lose their ability to function properly. Patients are either placed on dialysis or receive kidney organ transplants in order to maintain their lives. We discuss in this brief review what some of the causes of kidney failure are and how to potentially prevent kidney failure. The process of receiving a kidney is also discussed along with the risks involved with such a procedure. While there are many precautionary measures taken before a patient receives a kidney, there have been significant improvements in the lives of patients once they receive a kidney. Survival rates have significantly increased with the advancement of medical procedures and treatments. Nevertheless, there are areas that can be further developed to increase the number of patients eligible for kidney transplants and to prevent deleterious side effects of drugs.

Introduction

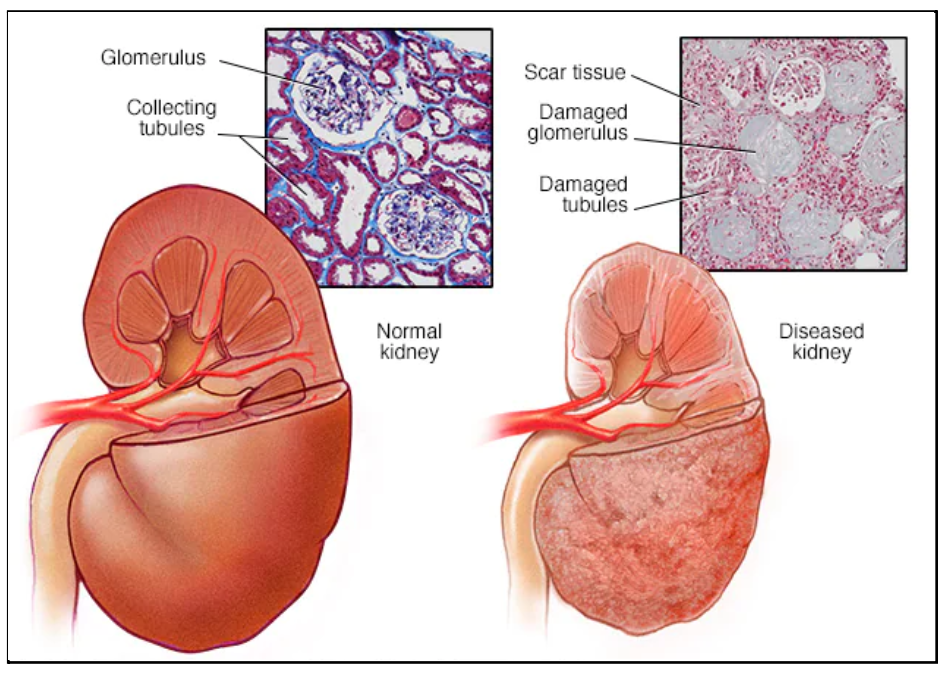

A kidney transplant is a surgical procedure in which a diseased kidney is replaced with a healthy kidney from a donor. The kidneys are a pair of organs located on each side of the lower abdomen that function to remove waste and excess fluid from the body by producing urine. Although humans have two kidneys, they can survive with only one functioning kidney. As shown in Figure 1, kidney failure (end stage kidney renal disease) can result if a kidney loses its filtration ability and allows certain wastes and fluids to gather in the body. People that are diagnosed with end stage renal disease must have a kidney transplant or undergo dialysis, where a machine mechanically removes fluid wastes from the body, replacing the function of the diseased kidney(s), in order to survive (Mayo, 2022). Examples of kidney diseases include lupus nephritis and kidney cancer, all requiring a kidney transplant to prolong the survival of the patient for as long as possible (Rodgers, 2022). Patients who are eligible for a kidney transplant surgery have a higher chance of a longer life expectancy and overall better quality of life. A donated kidney can be transplanted from a relative, an unrelated donor, or a deceased donor. Based on the statistics of current surgeries, patients who receive a kidney from a live donor have experienced more benefits than patients who have received a kidney from a deceased donor who has passed (Thongprayoon et al., 2020).

The history of kidney transplants comes with many unsuccessful attempts of experimentation, but has ultimately persevered past these setbacks. The first ever human kidney transplant was performed in 1936 as an allograft (human-to-human). The transplanted kidney left an area of the ureter unattached and because organ rejection was not yet understood, the transplant ultimately failed (Turner, 2018). After improving on the methods of transplantation, the first successful human-to-human kidney transplant took place in 1954 between identical twins (Williams, 2008). Based on prior failed kidney transplant surgeries, the medical team speculated the fact that a kidney transplant with identical twins may be successful. Amazingly, the kidney was able to adjust to the body of the recipient because the organ did not appear “foreign” when transplanted into the body due to the fact that the identical twins shared many similar traits. Both patients survived for nine years without immunosuppressive therapy (to be discussed later) after undergoing this surgery (Dziewanowski et al., 2011). Shortly after, the first successful kidney transplant between unrelated individuals took place in 1962. These monumental results would soon become a breakthrough in medicine offering people a solution to such a chronic disease.

Kidney transplantation has now become an option to increase the rate of survival and life expectancy for kidney disease patients. Although there are advantages to having the procedure performed on patients, there are prerequisites, limitations and risks involved in undergoing such a procedure. Patients are first put on a waiting list as a candidate to receive a kidney from donors, but a shortage of organs available for donation makes it difficult for this process to occur quickly. During this waiting period, patients must be placed on dialysis until they are eligible to receive a kidney organ. Nonetheless, this operation is not fit for everyone. For example, people of older age with a history of cardiovascular conditions do not have the option to have a kidney transplant. Patients may also not be eligible for a kidney transplant if they have a history with drug or alcohol usage, an inability to take post-surgery medications, or no health insurance (Rodgers, 2018). Although there are many advantages to kidney transplantations such as fewer food restrictions and higher energy levels for work or travel, there are some considerations to having the operation done. The risks of a kidney transplant include possible infection, damage, or bleeding in the surrounding organs in the lower abdomen. After the surgery, the patient will be required to take strong medications for the rest of their lifetime to prevent organ rejection by lowering their immune system (Hendry & Robb, 2020). These medications come with many side effects such as a higher risk of infections and diseases like cancer. An example of a significant risk factor is the development of diabetes mellitus, which has been shown to be acquired by almost 70% of patients with a kidney transplant post transplantation (Peev et al., 2014). It is crucial for the patient to consider all of these factors before deciding whether the surgical procedure is the best option.

II. The Importance of Kidney Transplants

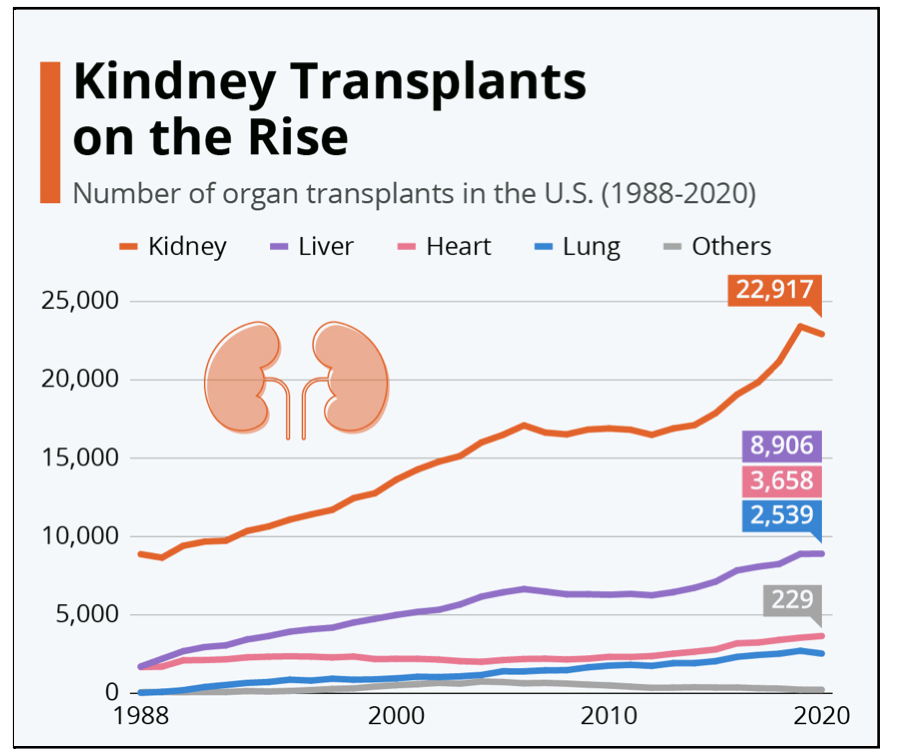

Kidney transplant surgeries are becoming more common as the number of kidney failures have dramatically increased over the years (Figure 2). This can be a result of common diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease which all increase the likelihood of developing chronic kidney failure. Each single kidney is made up of over one million small filtering units known as nephrons. Any condition, such as those previously listed, that may damage or cause potential harm to the nephrons can result in kidney disease (Digital, 2020). There are approximately 1 in every 3 adults in the world that are diagnosed with a type of diabetes with 1 in every 3 diabetic also developing chronic kidney disease (Walensky, 2021). High levels of blood glucose that are a result of the diagnosis of diabetes damages blood vessels in the kidneys which clusters and limits the kidneys’ abilities to filter waste. Furthermore, hypertension and obesity rates are increasing and have also been causes of kidney failures. Roughly 23% of patients who are diagnosed with kidney disease are also obese, demonstrating the close gap between the two conditions (Tran et al., 2016). Being overweight forces the kidneys to perform extra work to maintain balance by filtering waste and removing excess fluids that may come in addition to the supplemental body fat (Kovesdy et al., 2017).

Although kidney transplantation is the most prominent option for prolonging the lifespan of a patient with a diseased kidney, the procedure is not as simple as it may seem. In the United States, there are over 3,000 new patients added to the kidney organ transplant list each month, making it extremely difficult to find and receive a kidney in a short period of time. There are at least thirteen people who die each day waiting for a kidney, and others are put on dialysis to rely on the machine until they find a matching donor (UNOS, 2016). There were more than 20,000 donor organs available for transplant in the United States in 2016, but more than 100,000 patients were on the waiting list to receive a transplant. Given the stringent requirements to qualify a patient to receive a kidney, not all donor kidneys can be transplanted thus increasing the number of donor organs at about 8% per year (USRD, 2020). As shown in Figure 2, the annual need for kidney transplants is significantly greater than any other organ transplant. Recent statistics show that there has been a record in both the number of total kidney transplant surgeries and also the number of lives saved in 2021. The number of living donors had substantially decreased in 2020 due to the outbreak of the COVID pandemic and although the number of living donors was slightly higher in 2021, the number was still significantly less as compared to previous years. There were more than 6,000 organ transplants performed in 2021, which was approximately 14% higher than in 2020. Note that from 2010 to 2020 the total number of transplants performed was about 7,000 (Figure 2). Because of the result of the recent pandemic, more kidneys have been donated from deceased donors in order to maintain the consistency of survival rates (UNOS, 2022).

Kidney transplants have significantly shown beneficial outcomes and significant improvements in the lives of patients. Because of how common kidney disease has become, the need for transplants only continues to grow. A living donor kidney survives on average anywhere from 12-20 years, whereas a diseased kidney organ survives around 8-12 years (BIDIC, 2022). Short term rejections (within 3 months of surgery) occured in about 17.3% of patients 10 years ago, but have significantly decreased to around 4% as of current statistics (Lee et al., 2021). Survival expectancy rates of kidney transplants ranged around 75% around 10 years ago (Walensky, 2021), but has risen up to around 94-97% as of 2022 (BIDIC, 2022). This is mainly due to the increasing number of successful surgeries every year. The improvement of national transplant statistics comes from the benefit of developing medicine and research.

The most common age group to develop both kidney diseases and receive transplants is between 50-64. Although more than 45,000 individuals in this age group were on waiting lists for a kidney in 2021, current improvements in medicine and transplant surgery have nevertheless given these people the potential to live longer with less complications (Elflein, 2021). Unfortunately, there are many food restrictions and physical limitations that all kidney disease patients endure while living on dialysis. Having a kidney transplant relieves these individuals from the restrictions put on their daily life, which thus allows them to live healthier and more comfortably (Lee et al., 2021). Kidney transplants help to save the lives of over 20,000 individuals (i.e. actual living recipients of kidneys and patients who match for a transplant) every year (UNOS, 2022).

II. The Types of Kidney Transplant Rejections

The immune system protects the body by identifying cell markers and recognizing the cells as being healthy or foreign. Lacking these markers sometimes prompts immune cells to attack the cells to destroy them. Individuals have a unique and different collection of cells in their immune system. Foreign cells are removed from the body in order to provide protection from possible infections, illnesses, or diseases (Waltzer, 2019). The most common examples of foreign invaders include bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi that the immune system works to remove from the body. Foreign cells can also be healthy cells but from different individuals. Receiving a kidney transplant is seen as foreign by the immune system because the entrance of new antigens (cell markers on donor cells) prompt an immune response in the recipient. The immune system then works to reject the kidney by removing cells and antibodies that may cause potential harm. Transplant recipients therefore take immunosuppressive (anti-rejection) drugs to prevent damage to the kidney. It is extremely crucial to take these medications at around the same time every day in order to avoid kidney rejection (Hendry & Robb, 2020).

One of the three main types of kidney rejection is hyperacute rejection, which occurs within the first couple minutes of the surgery. This occurrence is irreversible and immediately results in the loss of the transplanted kidney and must be removed from the body promptly. Hyperacute rejection is diagnosed when the patient experiences immediate symptoms after surgery. Diagnosing this type of rejection is not too difficult, and even a simple urine test can diagnose or predict a rejection. Hyperacute rejection is caused by already existing antibodies that recognize the foreign kidney and cells from the donor and act immediately to reject this outlier. Fortunately, hyperacute rejection has now become extremely rare due to a special test called a crossmatch, which is completed before the transplant takes place. Instead of having the patient undergo the entire procedure leading to the surgery just to find out there is no match present, there are now prerequisites that are done which can determine superficially that there will be no severe reaction with the kidney. The tissue cross match is used to check how the immune system of the recipient may act to the placement of the new donated kidney (KHSCN, 2019). A positive result of this crossmatch indicates that the antibodies of the recipient will attack those of the donor, thus making the kidney unsuitable for the transplant process. A negative result of a crossmatch implies that there is no reaction between the antibodies of the recipient and the donor, thus making the kidney suitable for the transplant (Smoot, 2021).

Acute rejection is the second and most common type of rejection that is prone to happen anytime, but most frequently occurs around the first three months post transplant surgery. About 15-25% of recipients who experience this type of rejection within their first three months of surgery (Czech, 2022). This is usually a significant cause of allograft dysfunction, which causes an increase in serum creatinine level and correlates to a decrease in glomerular filtration rates (Goldenberg et al., 2016). Symptoms that prompt the doctor to perform tests to further observe this condition include an elevated temperature, tenderness or pain over the kidney transplant, a rapid increase in blood pressure or body weight, or a sudden decrease in urine output (Czech, 2022). Although this rejection is possible to be reversed in most cases when treated early, it may also result in a negative impact on the long-term graft survival overall. There are many instances where failed kidneys are not able to regain their functions even with the use of maximal antirejection therapy (Goldenberg et al., 2016).

Lastly, chronic rejections occur when any of the alternate rejection processes never completely reconcile and they continue to occur over long periods of time. This type of rejection can also be a result of when immunosuppressants stop regulation in the immune system due to their side effects. Chronic rejections typically occur in the first six months after surgery. Transplanted kidneys that have chronic rejection are found to have developed scarring of the tissue and damage to the blood vessels (Punch, 2022). Chronic rejection most commonly occurs among patients that have not received a sufficient amount of immunosuppression or medication following the transplant surgery (Henry & Robb, 2020). Symptoms that most likely indicate the presence of a chronic rejection in a kidney transplant are similar to those for the acute rejection, but come at later stages because of the different time periods the varying types of rejections occur at. Because there are no early symptoms for chronic rejections, this type of rejection is also commonly diagnosed by changes in laboratory tests or possible kidney biopsies. Although there is no medication to reverse chronic rejection, the kidney is generally able to last for months after the diagnosis is made by the doctor (Waltzer, 2019).

IV. How to Have a Successful Kidney Transplant Surgery

As previously mentioned, there are many different symptoms that may indicate possible kidney failure and prompt a doctor to run a diagnostic test on the patient. However in order to prevent the occurrence of these symptoms of failure as best as possible, it is crucial that the kidney from the donor and the patient are the right match. The three main blood tests that are used to check this are blood typing, tissue typing, and cross matching (Center, 2022). Blood typing is the first test done to determine if the kidney donor and the recipient have compatible blood types, indicating whether or not the kidney can be potentially transplanted. The next test after passing the initial blood typing exam is the tissue typing test, which is accomplished through routine testing and short turn around testing (STAT). Blood is drawn from the inside of the cheeks to determine if the potential donor and the recipient have a compatible HLA or tissue type (Center, 2022). As briefly mentioned above, cross matching is the ultimate step before the kidney officially becomes approved to be a donor for the recipient. Samples of blood are taken from both the donor and the recipient, then the blood cells of the donor are mixed with the serum of the recipient. A negative crossmatch result indicates that there is no presence of antibodies attacking the donor while a positive result shows that the kidney is not suitable for donation (Smoot, 2021).

However in order to prevent rejection of the kidney after the transplant surgery is completed, doctors prescribe immunosuppressants to help the newly transferred kidney survive in the new recipient’s body. The immunosuppressants must be taken every day for the rest of the recipients’ lives to prevent harmful interactions between foreign antibodies that may cause serious damage. The dosage of the medication is adjusted because of the many side effects that also commonly occur among patients as a result of the immunosuppressants. The most common side effects are constant migraines, hair loss, high blood pressure, or nausea, which can all become a consequence of taking the medication every day (Kalluri, 2012). Prednisone, tacrolimus, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, imuran, rapamune are among the most commonly prescribed immunosuppressants. Because there is such a wide variety, most patients take a combination of around three of these listed drugs (Trotta, 2021). About 6 months to a year after the kidney transplant surgery is administered, the dosage of the immunosuppressants are usually lowered in order to prevent the presence of the common side effects.

Conclusion

Despite all the information that has been gathered on this topic of kidney transplants, there are still a few questions that have been left unclarified. For example, why do women have a slower overall progression to end stage renal kidney disease than men? There are always biological and systematic factors to consider, but it is unclear whether the rates of progression are due to different accesses to care or possibly the true differences in the severity of their diseases. Furthermore, why are there always more women donating their kidneys than men? This question also lacks a clear answer and there are so many unique possibilities ranging from risks of kidney disease, personal requests, cultural factors, and much more. There is always a vast difference between genders regarding their access to care for their conditions, but there is not necessarily enough data obtained to recognize the range of these differences.

Chronic kidney disease and end stage renal disease are both extremely common, but medicine has shown progress in decreasing the side effects as a result of these procedures. However, there is still plenty of work to be researched and done. Improvement on the medical and treatment front such as ongoing clinical trials for different cell therapies to minimize the side effects would be an example of a beneficial approach to take the next step in the research. Due to the deleterious side effects of immunosuppressant drugs, more focus has been drawn to immunotherapeutics and cellular therapies to use the body’s own immune system to suppress activated immune cells that target the transplanted organ. There are ongoing clinical trials as well as numerous research projects all aiming to develop breakthrough cellular therapies that are more natural to the body and potentially safer options than drugs.

Works Cited

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. (2022). The Benefits of Kidney Transplant versus Dialysis. BIDMC of Boston. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.bidmc.org/centers-and-departments/transplant-institute/kidney-transplant

Buchholz, K., & Richter, F. (2021, March 11). Infographic: Kidney Transplants on the rise. Statista Infographics. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/chart/21110/organ-transplants-timeline-us/

Center, U. C. D. T. (2022). Matching and compatibility. UC Davis Health. Retrieved April 23,2022, from https://health.ucdavis.edu/transplant/livingkidneydonation/matching-and-compatibility.ht ml

Czech, K. (2022). Immunosuppression and rejection. Immunosuppression and Rejection | UI Health. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://hospital.uillinois.edu/primary-and-specialty-care/transplantation-program/kidney-t ransplantation/transplant-process-and-what-to-expect/immunosuppression-and-rejection

Digital, C. (2020). Risk factors. Kidney Health Australia. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://kidney.org.au/your-kidneys/know-your-kidneys/know-the-risk-factors

Dziewanowski, K., Drozd, R., Chojnowska, A., Dziewanowska-Rogalska, M., & Parczewski, M. (2011, July 27). Kidney transplantation among identical twins: Therapeutic dilemmas. BMJ case reports. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3149447/

Elflein, J. (2021, November 19). Organ waiting list by age United States 2021. Statista. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/398516/number-of-us-candidates-on-organ-waiting-list -by-age-group/

Goldberg RJ;Weng FL;Kandula. (2016). Acute and chronic allograft dysfunction in kidney transplant recipients. The Medical clinics of North America. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27095641/

Hendry, R., & Robb, M. (2020). Benefits and Risks of a Kidney Transplant. NHS choices. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/organ-transplantation/kidney/benefits-and-risks-of-a-kidney-transplant/

Kalluri, H. V., & Hardinger, K. L. (2012, August 24). Current state of renal transplant immunosuppression: Present and future. World journal of transplantation. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3782235/

Kidney Health Strategic Clinical Network, Alberta Health Services. (2019). Living kidney donation. MyHealth.Alberta.ca Government of Alberta Personal Health Portal. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://myhealth.alberta.ca/KidneyTransplant/living-kidney-donation/testing/tissue-typing -and-crossmatch

Kovesdy, C. P., Furth, S. L., Zoccali, C., & World Kidney Day Steering Committee. (2017, March 8). Obesity and kidney disease: Hidden consequences of the epidemic. Canadian journal of kidney health and disease. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5433675/

Lee, H. S., Kang, M., Kim, B., & Park, Y. (2021). Outcomes of kidney transplantation over a 16-year period in Korea: An analysis of the National Health Information Database. PLOS ONE. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0247449#:~:text=A cute%20rejection%20occurred%20in%2017.3,and%2056.7%25%20after%2015%20year s

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2022, January 14). Kidney transplant. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/kidney-transplant/about/pac-20384777 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2022). Healthy Kidney vs. diseased kidney. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/chronic-kidney-disease/multimedia/img- 20207486

Peev, V., Reiser, J., & Alachkar, N. (2014, August 27). Diabetes mellitus in the transplanted kidney. Frontiers in endocrinology. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4145713/

Punch, J. (2022). Kidney Transplantation: Past, Present, and Future. What is chronic rejection? Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPST/transplant/html/chronic.html

Rodgers, G. (2018). Choosing a treatment for kidney failure. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/kidney-disease/kidney-failure/choosing-treatment

Rodgers, G. (2022). Kidney disease. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/kidney-disease

Smoot, K. (2021, May 12). Incompatible kidney transplant: Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center. Incompatible Kidney Transplant | Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/transplant/programs/kidney/incompatible

Smoot, K. (2021, May 12). Incompatible kidney transplant: Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center. Incompatible Kidney Transplant | Johns Hopkins Comprehensive Transplant Center. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/transplant/programs/kidney/incompatible

Thongprayoon, C., Hansrivijit, P., Leeaphorn, N., Acharya, P., Torres-Ortiz, A., Kaewput, W., Kovvuru, K., Kanduri, S. R., Bathini, T., & Cheungpasitporn, W. (2020, April 22). Recent advances and clinical outcomes of Kidney Transplantation. Journal of clinical medicine. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7230851/

Tran, M.-H., Foster, C. E., Kalantar-Zadeh, K., & Ichii, H. (2016, March 24). Kidney transplantation in obese patients. World journal of transplantation. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4801789/

Trotta, E. (2021). Antirejection Medications after Kidney Transplant. Cincinnati Childrens. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/health/a/immuno

Turner, N. (2018). History of kidney transplantation. edrenorg. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://edren.org/ren/unit/history/history-of-kidney-transplation/

U.S. Department of Health and Science Services. (2022). Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. OPTN. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/news/all-time-records-again-set-in-2021-for-organ-transpl ants-organ-donation-from-deceased-donors/

United States Renal Data System. (2020, October 20). Statistics · the kidney project. The Kidney Project. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://pharm.ucsf.edu/kidney/need/statistics

UNOS News Bureau. (2022). Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. OPTN. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/news/all-time-records-again-set-in-2021-for-organ-transpl ants-organ-donation-from-deceased-donors/

UNOS. (2016, January 11). Organ donation and Transplantation Statistics. National Kidney Foundation. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.kidney.org/news/newsroom/factsheets/Organ-Donation-and-Transplantation- Stats

Walensky, R. (2021, May 7). Diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/managing/diabetes-kidney-disease.html

Waltzer, W. (2019). Understanding transplant rejection. Understanding Transplant Rejection | Stony Brook Medicine. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from https://www.stonybrookmedicine.edu/patientcare/transplant/rejection

Williams, A. V. (2008). A timeline of kidney transplantation. A Timeline of Kidney Transplantation: Overcoming the Rejection Factor. Retrieved April 23, 2022, from http://waring.library.musc.edu/exhibits/kidney/Transplantation.php

About the author

Emily Kim

Emily is currently a junior in the Academy for Medical Science and Technology at the Bergen County Academies High School. She is also a competitive nationally ranked swimmer and is looking to pursue medicine in the future.