Author: Ana Mao

Mentor: Dr. Isaac DiIanni

Shanghai High School International Division

October 1, 2021

Educational inequality is an extremely crucial and complex problem due to the fact that there are actually various factors that might lead to the inequality of education in society such as a lack of educational resources in urban and rural areas as well as regional inequality. However, the most significant origin of the cause to the educational inequality in China is the feudal ideologies and policies from a thousand years ago. In 1978, undoubtedly, China achieved tremendous economic success due to its economic reform (Henan), but the educational inequality was hard to solve or eliminate since the radical Chinese culture had passed from the generation to generation. The feudal ideology really had an affect on unequal allocation of resources and opportunities for education. However, as time elapsed, the educational system also improved a lot compared to the previous ones. The essay will mainly focus on the changes of educational inequality in China caused by feudal ideology and the differences between rural and urban areas regarding making the better the educational system.

Gender inequality

Gender inequality is definitely the reflection of both social and economic inequality in China. The radical ideology of gender inequality has already been present in China for a long time and gradually became the predetermined arrangement in society, which even appears in the system of language in Chinese culture. There are also many different phrases and sayings for the son and the daughter, for instance: wangzi cheng long (“Expect one’s son to have a bright future/ Expect one’s son to be a dragon”) ; shengge nǚer peiqianhuo (“The birth of a daughter means the loss of money)” (Ganzhi Di). According to the conventional thoughts that formed throughout history, in patriarchal world, there is a stereotypical assumption that men are more valuable than women that men are not only more powerful but intrinsically more worthwhile than women since only men can deserve power and privilege.

A vast majority of families still expect to rely on sons for old-age support, and are supported with by the traditional saying, “Sending girls to school is useless since they will get married and leave the home” (Hannum12). Compared to boys, girls face lower educational expectations, which measures commonly used to capture educational ambitions— specifically, they indicate the level of formal schooling that one would like to complete, and a greater likelihood of doing household chores due to social acceptance. Even though some girls outperform some boys in some academic areas, they still do not have the opportunity or chance to go school to attain advanced education. Consequently, most families only send the boys to school while the girls mainly stay at home learning how to do the housework due to the fact that most parents have higher expectations of boys than of girls that girls are unlikely to succeed in the labor market in the future. “In China, Li and Tsang (2005) suggest that, because a good marriage is more important than a good job for rural girls’ long-term welfare, some parents may think more about maximizing the chances of a good marriage than about investing in long-term career options”(Emily Hannum). These examples also suggest that the cultural norms in China have lead to the different socialization of boys and girls.

The conventional ideology mainly exists in the rural areas in China since more children have to compete with more siblings within a family. Especially large gender gaps can be found in rural Jiangxi, Anhui, and Sichuan provinces. For instance, according to the study by Li and Tsang, in Gansu and Hebei provinces, there are 400 hundred households who revealed that they had lower educational expectations for girls than for boys (Li and Tsang). Thus, in these rural areas, most girls stay in the family to help their parents do some farm work and wait to marry a man in the future. Most educational opportunities will be given to their sons due to the cultural norms. Another case study of Gansu province shows that 84 percent of the poorest boys and 90 percent of all other boys in the survey were enrolled in school. About 81 percent of the poorest girls and 85 percent of all other girls were enrolled. Poor girls are the most disadvantaged because the boys practically absorb all the educational resources (Emily Hannum).

As a result, men have a greater opportunity to attain educational resources due to the feudal ideology(traditional ideology in China: people favor boys over girls)in place, which absolutely affects the trend of the education since a lot of girls do not even have the chance to contribute to the society or pursue their dreams. Inevitably, families still apply the feudal ideology when making decisions on education, and girls’ dreams continue to be buried in their own hearts.

Educational inequality in urban and rural areas

Furthermore, educational inequality occurs obviously in the urban and rural areas due to the unequal allocation of resources and faculties. The hukou system has the direct relation to the separation of urban and rural areas. The hukou system was established in 1958, and was initially used by the Communist government as a means of separating rural and urban populations and restricting rural-to-urban movement (Solinger, 1999; Liang et al, 2007; Kwong, 2006). Consequently, the hukou system not only makes it difficult for rural populations to gain permanent status of residence in urban ares, but also it results in residents in rural areas starting to lack in sufficient state provisions (Henan Cheng). The rural Chinese had to be self-reliant and contribute to the society without any support from society. The migrated workers from rural areas to urban areas did not have rights to enjoy the same benefits as their urban counterparts (Qiang Ren and Qiang Fu), which caused the huge differences between urban and rural areas in China.

The substantial urban-rural disparities are mainly due to disparities of the teaching resources and school facilities. According to the study by Wang, in 2001, 40.9% of primary school teachers in urban areas had finished secondary education, while only 20.3% of their rural colleagues had done so; while 23.5% of middle-school teachers in urban areas had at least graduated from tertiary schools, only 9.4% of their counterparts in rural areas had achieved that level of education (Qiang Ren and Qiang Fu). The advanced human capital is actually limited and scarce in rural areas since most qualified human capitals are more incentivized to stay in the city to teach since they can earn higher income. In addition, the rural areas will mainly hire some Minban teachers(community sponsored teachers) who have lower levels of education due to the scarcity of qualified teachers. It shows the striking disparity of the levels of human capital in rural and urban areas, which indicates that students in rural areas cannot possibly attain the accessibility of the advanced resources of teaching. In rural areas, they do not have enough money to buy the teaching equipment, which also leads to the subordinate level of education to students. According to the China Human Development Report, the illiteracy rate was about 11.6 percent in rural areas, which was three times than the illiteracy rate in urban areas. From the evidence, people can clearly see that the illiteracy rate in rural areas is high due to an unequal allocation of resources and human capital. Consequently, it even drags the educational gap to become larger and larger.

Educational inputs such as school financing or funding also cause the crucial inequalities. According to the study by Yuan, “the average urban primary per-student expenditure was 1.86 times that of rural per-student expenditure in 2001. The urban-rural gap in educational finance was even greater at the secondary level: per-student expenditure of lower secondary education in urban areas was almost double that of per-student expenditure in rural areas” (Henan Cheng). The government policy of previous times in China also allocated disproportioned resources of education in two areas and neglected the special needs in rural areas such as textbooks, tables, etc. The rural areas during that time did not have enough wealth and because of the lack of support from the government, they could not even have the opportunity to improve the educational resources. Most students did not even have the chance to graduate under that poor educational system and even some families forced their children to quit school due to the fact that they could not continue to afford for their children to study in school. The low levels of resources also could not attract a lot of students in the rural areas to study and thus led to lower school enrollment. As a result, the disparity between rural and urban areas became even wider due to the huge inequalities of the teaching resources and human capital.

Better trend in education inequality

Obviously, the educational inequality was extremely hard to eliminate, but it gradually became better and better in China.

As time elapsed, political priorities and education policies dramatically shifted and changed throughout the history of the People’s Republic of China. The purpose during the China’s period was to emphasize economic development and social equality by implementing various policies in order to reduce the educational inequality.

In 1949, the central government tried to arrange the new educational system within China, which was totally different from the previous one. Firstly, the system should would have the right political nature and be led by the Chinese Communist Party. Secondly, it would serve the needs of rapid economic development. Many universities were reduced due to the fact that, in this case, it helped the government ease burdens(Ouyang Kang). “In 1951, one-third of all primary and general secondary-school teachers were employed by Minban schools, which refer to the private educational institution. Adult-education programs also contributed substantially to the expansion of educational opportunities in rural areas. Winter schools and spare time literacy programs in the early and mid-1950s affected tens of millions of peasants; worker-peasant schools enrolled smaller numbers of students, but many of these students continued on to college. The effectiveness of these efforts in improving literacy among peasants is well documented” (Emily Hannum).

In 1958, the Great Leap Forward movement created the new educational policy to motivate the equality of education. Many policies during the movement focused on basic education and many universities were moved into the rural areas. For instance, more work-study opportunities and part time-schools were opened in the rural areas in order to expand the opportunities for poorer people. Thus, the rural students had the chance to attain better educational resources. In 1977, the national standardized examination, called gaokao, was highlighted, something extremely meaningful for the the Chinese society. According to Wang and Ross (2010), the gaokao brings about opportunities for success and social mobility, which is especially attractive to the students in rural areas where opportunities to economically improve their well-being and lives are scarce. Every student in every area of China has the opportunity to sit the gaokao, no matter from the rural areas or urban areas, which can even be the turning point for rural students. There was a huge expansion in university students immediately after the change of political systems in education. “The number of university students increased from 89% in 2001; the percentage of those who could enter university increased from 9.8% in 1998 to 13.2% in 2003; Master’s degree students increased 93%; and Ph.D. students increased from 45,000 in 2001 to 77,000 in 2003, an increase of 71%. It is more meaningful if you think that all of these increases happened in three years and the numbers of university lecturers did not significantly increase. The proportion of university lecturers to university students changed from 1:8 before 2001 to 1:16 in 2003”(Ouyang Kang). Moreover, the government started paying more attention on the educational system and resources in the rural areas, and increasingly provided more funds in order to ensure the rural students’ sufficient resources.

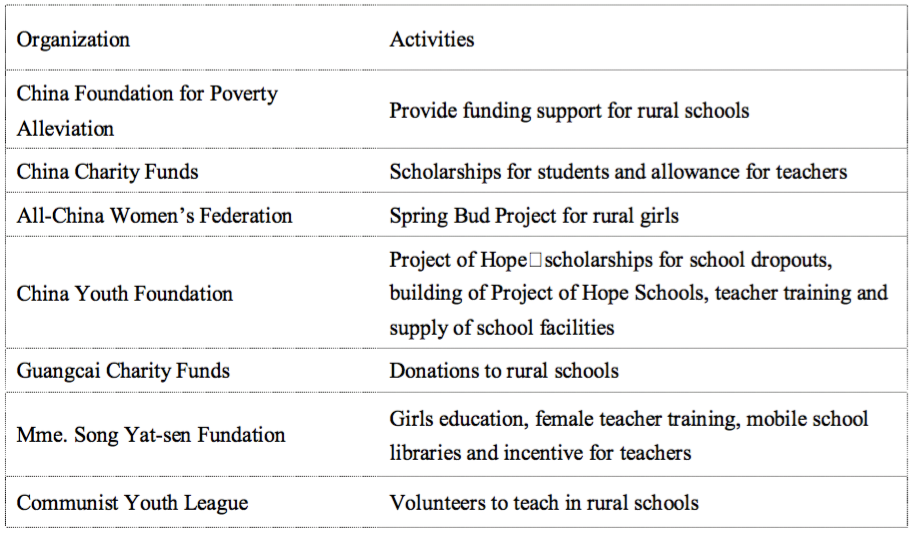

During 1985 to 1990, China started to promote the nine year compulsory education. The People’s Congress passed the decision of the new educational system and that “all the children at age of six should have the right for schooling regardless of gender, ethnicity, or race.” The law also requires that “the state, the community, schools, and families should guarantee the right of all children for schooling” (Zhao Tiedao). The ideology of “education for the people and by the people” promoted China to construct a fair society and let every child has the right to access education. Consequently, massive publicity campaigns raised funds to improve school facilities. Therefore, the proportion of dilapidated school building reduced from 17 percent to 2 percent, which meant that the conditions of schools were improving and provided solid groundwork for universalizing compulsory education in rural areas (Zhao Tiedao). A lot of institutions also raised funds and donated money to rural areas in order to help students in the impoverished areas get the balanced educational resources. From the 1996 to 2000, communities including some overseas contributors donated almost 31 billion RMB to support the rural compulsory education program. For instance, the Project of Hope raised 2 billion RMB for construction of 8,300 new schools in rural villages, which attracted 2.3 million dropout children back to school. Besides, 10,000 sets of library books were provided to rural schools and 2,300 rural teachers were trained. The Spring Bud Project, implemented by the All-China Women’s Federation, raised 500 million RMB which assisted getting 1.3 million girls from poor rural and ethnic families access to schooling”. (Zhao Tiedao). By changing the educational system into the nine year compulsory educational system, China reduced the illiteracy rate and more people could enjoy the equal rights of education. The situation of educational inequality became better and better.

Furthermore, the feudal ideology of gender inequality was gradually eliminated in mind and practice, and women started to have more rights. In 1949, newly introduced marriage and labor laws improved the social statuses of women and peasants. It was the turning point to turn the situation for women. During the time of the cotton textile industry, women proved their power to earn a lot of income and changed the perception of women being less capable than men. “For women to earn high incomes in today’s world, however, it is not necessary to have identical conditions to those in Imperial China. With advances in technology and changes in institutions, economic opportunities favoring women provide a richer variety of ways for women to earn high incomes today” (Xue, Melanie Meng). Women also had the same strength to complete the tasks as the men. As more people get educated, the ideology of gender inequality started to get adjusted and alternated toward an equal and fair path. Although the cultural norms still exist nowadays, women have equal rights, and have the ability to express their thoughts, and can gain the same level of education.

In China, educational inequality was an extremely serious problem due to the social norms of the ideology called gender inequality and unequal resources in rural and urban areas. However, after the long term of changes, the educational inequality started to eliminated and everyone has the rights to attain the same level of education in China.

Citations

Cheng, Henan. Inequality in Basic Education in China: A Comprehensive Review. 17 Aug. 2015.

“Gender Inequality of Classical Chinese: A Study of Gender-Based Words – ProQuest.”

www.proquest.com, www.proquest.com/openview/eb1426c7b73fa36727c7f66616a90aa8/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y. Accessed 20 Sept. 2021.

Qiang, Fu. Educational Inequality under China’s Rural ^ Urban Divide: The Hukou System and Return to Education. 2010.

Hannum, Emily, et al. Family Sources of Educational Gender Inequality in Rural China: A Critical Assessment. Elsevier, Sept. 2009.

book118.com. “《浅谈我国公民受教育机会不平等的原因及对策.Pdf》-支持高清全文免费浏览-Max文档.” Book118.com, 2015, max.book118.com/html/2015/0729/22212459.shtm. (Chinese)

“Study: Gender Inequality Serious in Rural Areas.” www.china.org.cn, www.china.org.cn/english/China/141286.htm. Accessed 20 Sept. 2021.

Wang D 2003, “China’s rural compulsory education: current situation, problems and policy alternatives”, WP 36, Institute of Population and Labor Economics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing, http://iple.cass.cn/file/36.pdf

Hannum, Emily, and Yu Xie. Trends in Educational Gender Inequality in China: 1945-1985. 1994.

Adams, Jennifer. Girls in Gansu, China: Expectations and Aspirations for Secondary Schooling. ScholarlyCommons, 2008.

Kang, Ouyang. Higher Education Reform in China Today. 2004.

TSANG, MUN C. INTERGOVERNMENTAL GRANTS and the FINANCING of COMPULSORY EDUCATION in CHINA. June 2001.

Zhang, Tiedao, et al. Universalizing Nine-Year Compulsory Education for Poverty Reduction in Rural China. 25 May 2004.

Xue, Melanie Meng. High-Value Work and the Rise of Women: The Cotton Revolution and Gender Equality in China. Dec. 2018.

About the author

Ana Mao

Ana is currently a Senior at the Shanghai High School, International Division.